It’s condition inspection time again for the ol’ box kite, hence my grumbling mood. It’s like this every year. I curse the zillion little screws, some #8s, some #10s, a few graduated to #12s or, to heck with it, lag bolts as the wood they screw into yawns open with each turn of the Phillips.

Yes, mine is an old-school, rag-and-tube flying contraption so everything is handmade—and I think by a guy who was in a hurry. So opening it and putting it back together again is not an efficient or overly happy time. I’d rather be flying and it gets you wondering why it all has to be so difficult.

Thanks to two marriages in the family and an unscheduled but enjoyable major trip followed by one of the wettest winters in memory, my not-flying life borrowed plenty from my flying life last year. Thus, the old biplane did far more sitting than soaring since the last condition inspection—just 21.7 hours if you must know—which is small threat to the tire tread, you must agree.

So few hours between inspections inevitably leads to skipping a few steps during the look-see. Now, before you scorch the internet with venomous bile on how it’s unconscionable to skip anything, what I mean is the wheel pants did not come off this year and a few—not many—access panels remained in place. You can still eyeball it all and my authorizing A&P and I are both comfortable we’re seeing what needs to be seen.

What has been amazing is how much easier the annual chore is going simply by leaving a few hundred PK screws in place. We all understand how not handling a boxful of screws can save time, but internalizing just how much of your life has been spent opening and closing the same old areas truly drives the concept home. In fact, I’ve been so struck by the difference I’ve noodled on the situation in the back of the hangar during the recliner chair visits. I’ve concluded my condition inspection issues are typically threefold: accessibility, oil mess and heat affectation.

The Big Three

By far the greatest of these is the eternal labor of getting at it then covering it up again. In practical terms this means removing outer skins or working around fabric covering. Or it might mean complications from “features” such as a two-piece cowling incorporating a landing light, three air inlets and cowl flaps behind a three-blade propeller.

Oil mess is a variable, of course. Some engines slobber more than others, some airplanes do more oil-spilling aerobatics than others, some have owners who take their time tracking down and fixing weeping oil lines and such. But even the best of ’em get misty-eyed at the thought of flight and that can mean oily hands and clothes to anyone daring to get within a yard of their sleek bodies. Heck, I open my hangar door and a spot of 50-weight appears on my shirt.

Heat affectation is largely an exhaust thing. I’ve got two tailpipes tucked sleekly against my lower fuselage and you can’t believe what blowtorches they are. You know those nifty white shark-fin transponder antennas? The plastic streamline coating on those looked like dried lava after maybe five hours downstream of my 540’s exhaust. My cure was to retreat to a short rod antenna and offset it out of the exhaust stream; yours might be to extend the tailpipes a bit away from the airframe and take the airspeed hit. Beyond exhaust heat, general under-cowl heat death is, of course, par for the course for anything not Inconel. Zip ties might as well be potato chip sacrifices to the aviating gods. Avoid them except when front and center because you’ll be changing them.

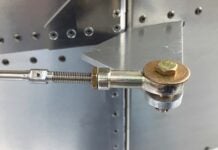

Over the years I’ve made many changes in order to make inspecting and servicing my plane easier. After all, easy jobs actually get done and done well, which makes for a safer, more enjoyable airplane, so this is real win-win stuff. Good examples are fitting nut plates where nuts and washers once stood, using Koroseal lacing or electrical thread instead of zip ties, adding heat shields and blast tubes, moving that antenna out of harm’s way and so on.

But there is only so much you can do once a plane is built, so my plea is to all those building or to myself should I ever get the chance to either rebuild my labor-loving airplane or assemble a new one. And because access is the main issue, that is the first thing I would address. Big, hinged cowling doors for immediate access without removing the cowling are a great start. Multi-piece cowls with quick-release fasteners that come off in a snap are ever better.

And why not? You know you are going to service everything eventually, so why not make it as easy to get at it as possible?

Put a Zipper in It

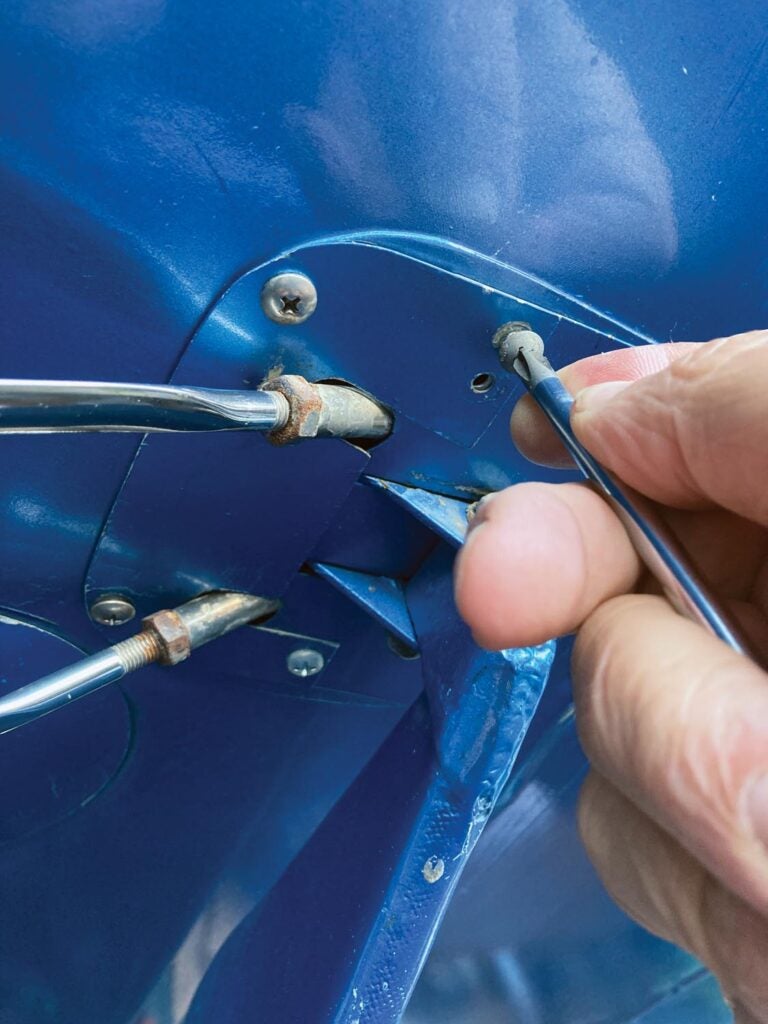

It may be indistinct now but decades down the Hobbs meter it might be necessary to visit some truly remote parts of your creation. The aft fuselage comes to mind, especially in a rag-and-tube airplane where there is no crawling down an aluminum taper to see where the rudder cables are rubbing. I don’t care how skinny your grandkids are going to be, snakes have difficulty navigating such spaces, so you might as well put an inspection panel in now.

One airplane comes to mind here, the N3N-3, which might be best described as the Stearman’s ugly sister. A product of the Naval Aircraft Factory and thus a government job, it was at least designed for servicing by draftees. There was no engine cowling, no wheel pants or gear leg fairings, and the entire set of metal fuselage skins on the left side—not the right, just the left—were held fast with Dzus fasteners. It could step out of its clothes faster than a Nevada sporting girl and anything inside was easily serviced.

Putting a zipper down the entire aft fuselage might be a bit much even for me, but I have entertained installing a long, unavoidably tapering to narrow inspection panel on the aft fuselage belly. Down there it wouldn’t offend our now delicately advanced sense of sight, yet it would be the easy way to get all the accumulating junk out, plus allow a fighting chance at the wiring and flight controls. Again, this might not be such an advantage (or sound engineering) with a monocoque plastic or metal fuselage, but it would be a godsend to rag-and-tubers.

Then there is getting behind the instrument panel. Doesn’t matter what your airplane is made out of here, sooner or later someone is going to have to go fishing in what looks like the basement of the phone company, so you might as well make it easy. There are many considerations thanks to the fuselage, panel and windshield all intersecting here, but some sort of removable panel sure makes sense. It might be making the instrument panel itself into a series of easily removed doors would work best.

Oil mess can only be addressed at the source, so just go electric and be done with it. That’s why the English never exported televisions, according to my sports car racing friends; they could never figure how to make them leak oil, and it could work for you too. But should you stick with an infernal combustion device, you’ll discover that the really tough leaks come from the case parting line, accessory case mountings or all those hoses and fittings. It’s possible to O-ring the case these days, so that might be a good idea to avoiding the Lycoming’s “snotty nose” leak, and again, easy access to the hoses and such makes changing them when necessary a far more palatable situation.

Otherwise, the big challenge for sure with oil is getting it in and out of the engine. Gravity plays a major role here, as is an oil drain you can actually reach. That might be something to keep in mind when routing exhaust tubing or deciding where to locate the drain. And remember, you’ll want to safety wire that drain once a year, so you might as well make it easy on yourself.

A final servicing thought for anyone building: lifting the airplane. It’s not often that lifting the entire airplane is necessary, but when it is, it sure would help if someone had engineered a way of doing it. Ask anyone changing wheels to floats annually or needing to snap in some new landing gear bungees.

Enough for now, I’ve got a condition inspection to finish.