Airplanes are born of time and tedium. Mostly tedium. A harsh statement, yet a true one. There’s just no way around deburring the thousands of holes in an aluminum airframe; certainly no way around filling them with rivets. (OK, there is. It’s the quickbuild kit option.) Rib stitching wings holds no charm after the first rib. Sanding fiberglass? Yah, that’s a hoot. Simple tasks—many quickly learned, like hammering a framing nail—constitute the bulk of aircraft construction. Perhaps that’s what makes building an aircraft seem dull at times; the basic skills are endlessly repeated. The hard part of homebuilding is not learning or executing the tasks. No, the hard part is initiating the execution of the tasks, which is to say the hard part is getting your ass off the couch to do the often-tedious work.

Inertia: Friend & Foe

Inertia exerts itself in two ways: It keeps things moving and it keeps things stationary. It can be difficult to change inertia from one state to the other. That’s good news if inertia is carrying your project forward. It’s bad news if inertia has stalled your progress. Finding the grip length of a bolt is a quick internet search away. Finding the motivation to install the bolt is not; that must come from within. Inside our minds we each have a searchable internet (or inner-net, if you will). It’s a personal history of experiences from which we can draw motivation or conjure failure. We bring the same personality to homebuilding that we bring to the other areas of our life. What drives you to polish your seldom-driven 1968 Nova five times each summer? If you can’t go a day without playing a guitar, what sustains that desire? Are you compelled to play no matter the environment, or do you need to keep one close by so when the mood strikes you can reach it from your couch? If having to clean brushes after a few relaxing hours of oil painting doesn’t stop you from oil painting, how can that translate to an aircraft project? Does the desire to paint spring from watching something develop of your own hand despite the mess and odor? What makes you strap running shoes on every day to run the same 4-mile route? Every rivet sets the same, so whatever you draw on for your runs you can draw on for each rivet. Marathons are run one step at time. Airplanes are built one step at a time.

On the other hand, if your history is littered with unfinished projects you stand a chance of repeating that pattern with a kit aircraft. I must quickly add that past failures do not guarantee a homebuilding failure. Those unfinished projects may have been started for the wrong reasons. Probe deep into your inner-net and evaluate why each project fell by the wayside. Be honest with yourself. Was it a time constraint? Money? Were they started on a whim? Did having a long-term project press on your conscience and cause you stress? Is a messy or cluttered surrounding intolerable to your sensibilities? You might discover a kit aircraft is a no-go no matter how much you are in love with the idea of building. You may also find that all along you’ve had an airplane project in you, not a car restoration or a basement remodel.

Overcoming Inertia

Neither I nor others can tell you how to keep your project moving forward. But, as I mentioned earlier, you have a lifetime of experiences—good and bad—upon which to draw to help determine what may motivate you. Here are a few things that motivate me.

I keep my projects near, or far. When I built Metal Illness I needed it close, like “in my garage” close. The circumstances of my life at that time dictated that my success hinged on the ability to quickly dip in and out of the project. Today, I don’t mind driving to the airport to work on my project. What changed? While building Metal Illness I had a family underfoot and wanted to be close to them. Today, I work mostly from home and live alone. Going to the airport is a welcome change of scenery.

I push multiple strings at once. There are hundreds of small projects within an airplane project. When I tell people I spent a year fitting my cowling they become catatonic at the thought, but it wasn’t a year of doing nothing but the cowl. I had other tasks in progress. While epoxy, microballoons or primer dried on the cowl, I was making progress in other areas—areas that used different tools and skills, which helped keep the project feeling fresh.

I focus on a single task. Quite opposite of pushing many strings at once, sometimes I focus on a single task; deburring an entire wing skin without pause, for instance. It’s my concerted desire to get it done, to slog through the boredom and move on. Deburring a skin and putting that tedium behind me is both a reward and the motivation to keep building.

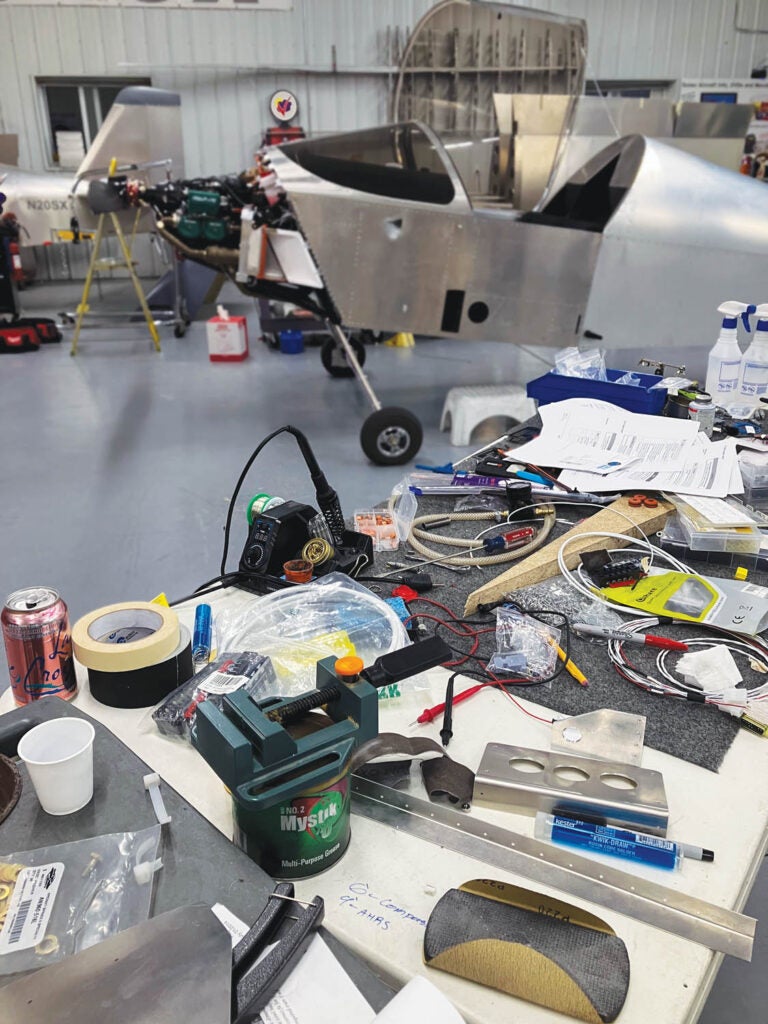

I leave the mess be (or stop to get organized). Yup, another contradiction. I generally don’t like clutter. Physical clutter creates mental clutter. Yet there are times I’ll let the metal chips, aluminum cutoffs, tools, rivet mandrels and free-ranging hardware accumulate because I’m making progress I don’t want to interrupt. But then, maybe suddenly, I’ll find it imperative to tidy up to keep progress moving. My need to clean usually strikes hardest at the beginning of a work session or when I begin working on a decidedly different part or subassembly. I’ve also found that cleaning up after a work session is a strong motivator for the next session.

I set goals, big and small. My goals vary in size and scope. Each work session begins with a minimum goal, set before I enter the shop, but never a time frame for completing it. It may be fitting and up-drilling the vertical stabilizer skin regardless of how long it takes. With that done I may stop, feeling accomplished, or press on with the new goal of removing the skin to deburr the underlying structure. Larger goals, such as completing the tail by a certain date, are set near enough to keep me working, but not so near they cause anxiety. I’m also not afraid to take a day off, which often energizes me to get back in the shop the next day to make up for lost time.

An Airplane Born of Your Own Hands

The satisfaction of building an airplane doesn’t come from the repetitive tasks (though there is a certain zen that settles in as rivets replace Clecoes and a smooth surface evolves from a smudge of microballoons). Few will claim riveting or sanding was the highlight of their airplane project. If the repetitive tasks provided the pleasure we’d all do fine dimpling holes in scraps of aluminum or mixing small batches of Aerolite adhesive while watching the [insert your favorite sports team here] take it to the [insert your least favorite sports team here] yet one more time. There’d be no need to buy #30 drill bits or sandpaper in bulk. There’d be no need to force the wife’s car into the harsh winter weather, heavy with guilt that the airplane must endure another winter in an unheated garage. Building an airplane requires looking beyond the tedium and repetition of the mundane tasks to find the personal rewards that move the project forward. The root satisfaction of homebuilding is watching an airplane take shape of your own hands. And for that, one must take action.