For my wife and me, it was important to have our kids learn a musical instrument. We lost out to sports with our son, so we made a commitment to be more steadfast with the three daughters who followed. We were making good progress until one day our eldest daughter informed us that she was bored with piano and was going to quit.

We were surprised at this declaration and knew it would be a mistake to just accept her resignation. We put together a careful plan of both stick and carrot, and worked diligently to keep her playing over a few difficult months. Then almost overnight something changed dramatically. She embraced the piano full on, practiced without coaxing and became not only an accomplished player but a teacher as well. Eventually she earned both a scholarship and a degree in music. We shudder to think what would have been lost if we had just caved when she wanted to quit.

I preface all of this because I have both lived and witnessed a similar challenge building Experimental aircraft. Modern advances in kit production—things like 3-D plans, quickbuild kits, hydroformed components, matched-hole machine-punch technology and preassembled wiring bundles—make a lot of the kit offerings in the marketplace infinitely easier to successfully turn into an operating aircraft for today’s builders than what our predecessors were faced with. Nevertheless, I very carefully selected the word “easier” as a synonym for “less difficult.” No E/A-B aircraft is easy to build and likely never will be. Anyone who says otherwise is either delusional or disingenuous. Inherent to significant challenges come great ultimate reward and satisfaction.

Oh, That Guy

We all know those rather annoying golden-handed craftsmen who are instant experts at everything they try. However, the vast majority of us, the bread and butter of the kit manufacturers, are average schmoes who on our first build experience find ourselves with a lot to learn and practice to overcome large gaps in our knowledge and experience. In terms of effort required, I would equate a first build project with learning a musical instrument or a foreign language. That doesn’t mean that a project isn’t doable, as thousands of successful builders can attest, it just means that it is going to take significant study, work and commitment along with, of course, the requisite AMUs—all of which contribute to the indescribable feeling of accomplishment that a successful result can generate. I am a firm believer that any average enthusiast with the commitment, desire and financial resources to complete a project can do so successfully. I am living proof of that.

I will venture to say that every first-time builder at some point in the build process will face a situation where dark clouds form over the shop. At least one episode of doubt, second-guessing or even despair is common. Pilots know that the number of landings logged should always equal the number of takeoffs. Unfortunately, the number of projects completed will never equal the number of projects begun. They just won’t. There are, however, steps that can be taken to increase the completion rate.

Before discussing some helpful practices to get projects completed, I want to make one thing perfectly clear. I fully realize that there are many situations where aborting a project is necessary and justified. Sometimes life has a way of getting in the way. Finances, health, family needs and the like can change dramatically and unexpectedly. And of course, some people just aren’t cut out for building or simply discover that they don’t have the desire to put forth the effort required. However, I also firmly believe that a disturbing number of projects get abandoned far too early when just a little more effort and motivation to get over the hump and/or out of the slump would have resulted in a successful completion.

If any current builders are currently experiencing doubt about your ability to finish, just know that you are not alone. We’ve all been there, and there certainly are lights at the end of the tunnel that actually aren’t oncoming trains. The following are some suggestions to help get a project to the finish line.

Don’t Make Rash Decisions

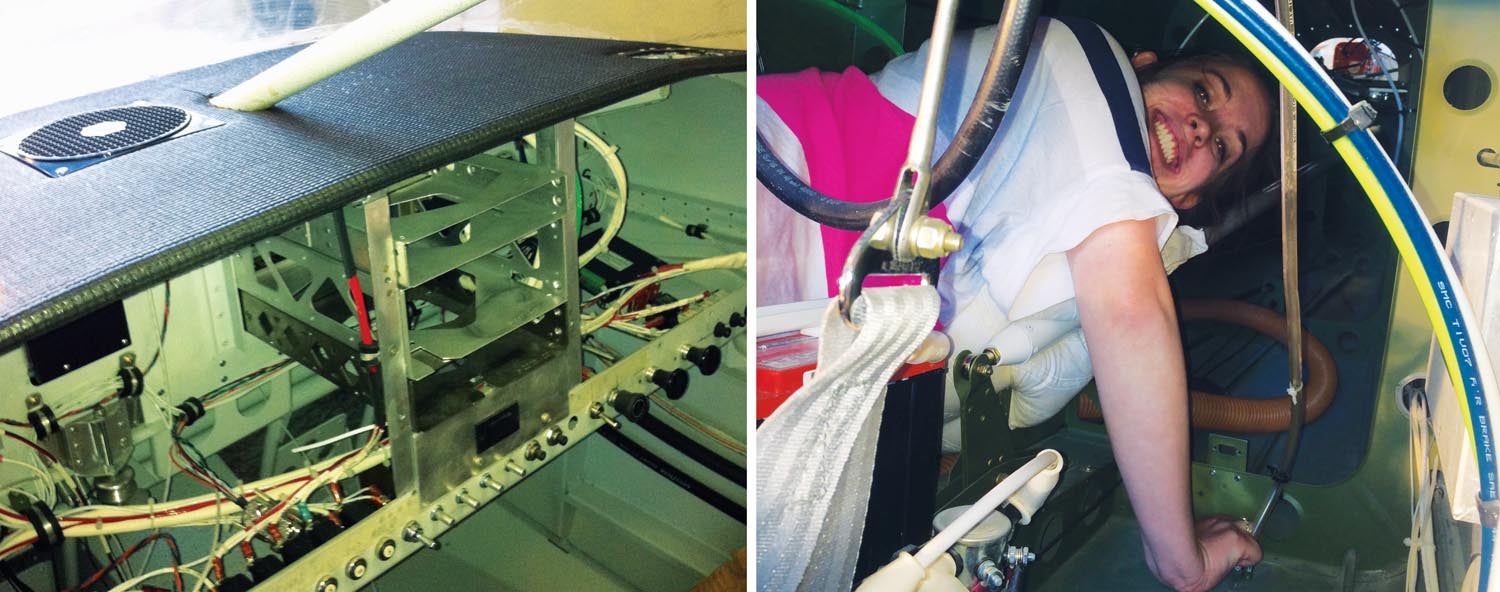

This starts at the decision to embark on a build and carries through the entire process. There is wisdom in making sure that significant others and family members are brought into the process early and have a decent understanding of the time and money commitment required. I had teenage daughters (twins) at home during the bulk of my build and some of my fondest memories were having them buried in the tail cone bucking rivets and then signing the area with their name and the date.

Family strife can be a significant headwind to a build project. Likewise, family support can be a terrific motivator.

Choose Well

Picking the right project to build should never be a spur-of-the-moment decision. There is wisdom for all first-time builders to stick to marquee manufacturers and models that have a significant history and volume in the marketplace. There is also wisdom for first-time builders (and most everyone else) to stick to major components like powerplants and avionics from well-established sources. In my relatively short experience in the avocation, I’ve seen several examples of kit designs, engine packages and even avionics that made huge promises about revolutionary designs and/or ridiculously low costs that often either never got off the ground or, if they did, soon crashed and burned (literally and figuratively). Nothing is more expensive than a cheap engine or more motivationally deflating than finding out that your exotic engine or avionics supplier just closed the doors before you even got the project flying.

I have mentioned before that one of the biggest benefits of this avocation is the wonderful community that a builder can become a part of. In a way, it isn’t about the airplanes—the airplanes are just a reason for the community to exist. When I started building, I quickly met a couple of people in my area who were pretty much at the same stage as I was. Having others around to support each other, answer questions and motivate, even playfully challenge each other goes a long way to help navigate a successful completion. We became friends, and have helped and supported each other long after our projects were flying. I have spoken to both of them in the last week. When doubts or frustrations appear, and they will, don’t be afraid to reach out for help.

There are lots of other ways to derive nourishment from the greater community. Membership in a local EAA chapter is a huge benefit. Additionally there are myriad internet-based communities and forums that connect builders from all over the world. For a common kit, I doubt there is a single step in the plans that doesn’t exist online in details, pictures or videos. Factory tech support is great, but often restricted to a few hours during the week. The same question can be asked on certain forums that will result in multiple and even immediate answers.

No discussion about media support would be complete without mentioning the magazines that were the original support media before anything else. Long before I was invited to contribute to this magazine, I was a huge and dedicated fan, and I will continue to be long after my contributions have been supplanted. I have many years’ worth of issues stored even though they’re all available online as well. I’m not involved in the marketing aspect at all, but I will shamelessly attest that I believe that this magazine brings immeasurable value for its cost. Yes, I still pay for a subscription. I also have some other general aviation brands in my aviation magazine collection going back almost 50 years when the aviation bug first hit me.

The Ultimate Stimulation

Two words. AirVenture/Oshkosh. If you haven’t been, just go. If you do sometimes, go every time. When seeds of doubt overwhelm us and the thought enters our mind of pulling the cannon plug, standing with your fellow builders and walking the acres of homebuilts will do wonders to restore your passion, reassure you of your abilities and generally just remind you of what got us started in the first place.

Building a successful Experimental aircraft project is a marathon, not a sprint. There are no trophies for assembly speed. I was still working full time when I was building and I found that periods of vacation were when a lot of productive work was accomplished. However, as a form of balance, I also discovered that alternating vacation periods to take a break from the project and focus time and attention on the family were equally of value.

Those of us who have been active in the community for some time have all seen the occasional entrant who blasts into the Rivetverse of Madness with all thrust and no vector, showing off paint schemes, workshop details and plans for three layers of IFR redundancy before the first kit order is even made. At full throttle it doesn’t take long for the money and enthusiasm to run out and, more often than not, the blaze-of-glory projects show up quietly for sale in a relatively short time.

What I have learned from observing a multitude of projects, successful and otherwise, is that slow and steady progress is what ends most often in success. Conservative and reasonable budgets, wise purchasing decisions, realistic goals and steady activity are vitally important. There will always be ups and downs—rivets will have to be drilled out and replaced, ideas that don’t pan out or knowledge gaps that will have to be filled. The best piece of advice ever given to me is something that has been around as long as the industry has, which is to simply go out every available day and do something in the shop, no matter how trivial. Just do something. Pick up a piece of trash on the floor or return a tool to its proper place. More often than not that one trivial accomplishment will spark new enthusiasm for more effort and real kitwork will result. Getting over the hump(s) makes gravity your friend on the backside and one day the time will eventually come when it is time to release the brakes and advance that throttle to the stop for the first time.

“…along with, of course, the requisite AMUs…”

I surrender. What is an AMU?

1 AMU = 1 Aviation Monetary Unit = $1,000