Perhaps we can best quantify Justin Meaders’ success by how he caught our attention. Arriving seemingly out of nowhere in 2018, he beat everyone in the highly competitive Formula 1 class at the Reno National Championship Air Races, a clear signal something special was at hand. We hadn’t seen the airplane before and only after tracking Justin down in the pits did we learn it was a brand-new ship. Furthermore, Justin had built and won from a wheelchair. Impressive.

Where Justin really won us over was after we asked him where he’d been and he answered to the effect, “Oh, down home in Texas testing until I got everything right.” This definitely made us interested because in amateur racing the emphasis is on fun, and almost everyone at Reno starts with a tentative, low-budget entry, followed by a protracted process—often agonizingly so—of gathering the experience, budget and finally the correct and sorted hardware to advance to the front. That means plenty of budget-cautious teams fumble their way forward or dry up and blow away after a couple of tries. But fun for Justin is winning, and he knew testing until he had a well-vetted hot rod and team under him was the shortest path to success.

Meet Justin

Justin’s start in aviation was both early and late. His dad was a pilot: “GA stuff, Cessna 172s,” he says. “I was about 5 when I first flew with him and got the bug.” But then Dad sold the airplane and moved to other things long before Justin could solo. Instead, Justin turned to motorcycles, both dirt and road racing models. It was a high-speed road racing bike accident that cost him the use of his legs when he was just 22 years old.

Competitive as they come and yearning for the freedom of mobility, Justin immediately turned to human-powered sports such as handcycles, racing wheelchairs, swimming and triathlon. And for sure he was good at it, making the podium in his first paratriathlon national race with the Challenged Athletes Foundation and training with the U.S. team at the world championship level.

Justin’s return to aviation in the later ’aughts came after plenty of experience flying with his dad and later with friends, so he was familiar with the basics and conventional controls. But as he went looking for a flight school, none seemed interested in training him for his private. “I kept getting denied.” Then a friend recommended Marcair Aviation, then at Northwest Regional Airport in Roanoke, Texas (now at KAFW), and “they treated me like family from day one.” Training took place in 172s and later in Citabria and Super Decathlon aircraft fitted with hand controls Justin provided.

Admittedly while we were looking elsewhere, Justin won Rookie of the Year in his Reno debut in 2016, along with fourth in the Silver race at 211 mph. Sensibly he had borrowed the mid-pack Quadnickel for his first year around the pylons. While the veteran Formula 1 Cassutt derivative certainly did its job getting Justin into pylon racing, it wasn’t the mount that was going to take him to the gold, so he focused on finishing his more modern, versatile Formula 1 racer that could win the gold but could also serve as an interesting sport flyer. The sport flyer portion of the equation makes sense in an otherwise purpose-built racing plane such as a Formula 1 when you consider Justin needs his special hand controls to fly. They’re an obvious rarity, so the practical solution for Justin is to build and own airplanes suited for him. To date no nondisabled pilot has been able to fly his hand controls, so Justin’s airplanes are pretty much Justin’s. Actually it’s no wonder pilots used to conventional controls find the transition to hand controls near-impossible because it was for Justin. He was used to conventional controls prior to his formal flying lessons and found two-handed flying a huge change. The difference is he had no other choice, and he obviously went native with his two-stick arrangement long ago.

Finding airplane construction enjoyable, Justin is now full-time as Limitless Air Racing Specialties in Mineral Wells, Texas. Currently in the shop is a Knight Twister Imperial build for Carl Robinson. It features a 9-inch fuselage stretch along with a set of wings suitable for Reno Biplane class racing. He’s also rebuilding Outrageous, another Formula 1 veteran, to accommodate Snoshoo fuselage skins on its Cassutt frame along with a CG change. Not to ignore backcountry flying, Justin finished up a Kitfox for himself in 2022, featuring his hand controls in addition to the regular stick and rudder.

The Snoshoo

Naturally, Justin’s most well-known build to date is what we’re looking at here, his F1 racer Limitless. Started in 2017, its story is typical of successful specialized aircraft thanks to a good number of aviation luminaries who’ve helped in its design and fabrication, along with a design pedigree that’s so intertwined with other race planes it resembles a wild wisteria vine.

Understanding Justin’s Snoshoo requires a quick history lesson whose starting point is way back in 1949 when Vincent Asp built a one-off Goodyear Midget class racer dubbed Shoestring. Ultimately one of the most famous and perhaps winningest racing airplanes of all time, Shoestring was a fixture in the burgeoning Midget and later Formula 1 air racing scenes in the early days, especially after it was later bought by Ray Cote, who flew it to many gold wins at Reno in the ’60s and later era. Its lightly potbellied fuselage coupled with rounded wingtips and tail group went against the aerodynamic thinking of its day, but no one could argue against its win record.

Ultimately even Ray Cote and associates Ken Stockbarger and Paul White thought they could best improve upon Shoestring with a new airplane employing Shoestring basics but more modern aerodynamic thinking. They called their new creation the SR-1 Snoshoo (iS NO SHOestring). While the new design incorporated the many hard-won lessons of campaigning Shoestring for decades, Cote and friends only got as far as building the SR-1 prototype’s spar, ribs and fuselage weldment before selling the enterprise to A. J. Smith and Alan Van Meter in 1982.

Smith, an engineer retired from a career at Cessna, teamed with Van Meter, a Boeing flight test engineer, to form Van Meter Smith Racing (VSR), which is Snoshoo headquarters. Interested parties can reach VSR at www.snoshoo.com. Additionally, Smith continues with his own Aerosmith Engineering; VSR and Aerosmith are co-located in O’Neil, Nebraska.

Several Snoshoos have been started, but to date the prototype and Limitless are the only flying examples. However, the prototype did fly a handful of hours before being taken apart for finishing but then sat for decades. Recently it was relocated to Alan’s hangar and may make the 2023 Reno air races. Justin also reports three additional Snoshoos are under construction around the country, but none are flying yet. Worth clarifying, there are internet reports of a Snoshoo named Miss Lynn that stall-spun while extending the glide after an engine-out some years ago, but that aircraft was actually a Casshoo. That’s a Cassutt with a Snoshoo wing and thus isn’t counted as a Snoshoo by the in-crowd. If nothing else, the breed earns props for creative model names.

Snoshoo Contruction

With just a handful of Snoshoos even under construction and only Limitless in public view, the design has remained mainly unknown. Furthermore, it turns out Limitless is an SR-1.1, an update of the original SR-1 Snoshoo design. We’ll begin by describing the straight SR-1 as an introduction to Justin’s plane.

Most fundamentally, the SR-1 family retains a welded 4130 steel fuselage primary structure in lieu of a composite tub such as popularized by Jon Sharp’s all-conquering Nemesis or several other “modern” Formula 1s. This is deliberate, with Van Meter noting the weight savings is a toss-up between the two construction methods given the Formula 1 footprint and steel tube having repairability and crashworthiness advantages over composite. He does concede the composite airplanes enjoy a greater usable interior volume advantage, as perhaps best seen in Nemesis because its pilot/builder, Jon Sharp, is a full-framed sequoia of an F1 pilot towering around 6 foot 4 inches.

Van Meter also notes, “We’re not structure guys,” referring to himself and fellow aerodynamicist, Boeing engineer and Limitless third teammate Jon Latall, so the Snoshoo understandably concentrates on shape rather than structure. Furthermore, tube frame or not, they say the Snoshoo can accommodate pilots up to 6 foot 5 inches, so big guys can have fun here, too.

The change allowing larger pilots was the elimination of the Shoestring-style rear spar carry-through in favor of a more Cassutt-like single spar attachment. This hugely opens the cockpit, as Shoestring would only fit pilots up to maybe 5 foot 8 inches. This also means SR-1.1 wings will fit on that Formula 1 staple, the Cassutt, and vice versa. This includes the torque tube aileron activation. Normally swapping wings is not a concern among different airplanes, but the ability to interchange or at least fit newer wings is a plus in Formula 1. Nearly every F1 features a removable wing for trailering, so changing wings is easily possible and everyone seems to have their own idea on updating their racer with a new wing. You could say there’s something of a wing-swapping culture in the F1 hangar.

The standard SR-1 wing is all wood, using a Sitka spruce spar and plywood skin but with a somewhat thick by air racing standards 14%, natural laminar-flow airfoil. Smith and Van Meter say the thicker airfoil—Shoestring’s was just 8% at the root and 6% at the tip—gives a more progressive, more easily managed stall, and while a touch slower in a straight line the fatter wing does not generate as much induced drag in the turns. And as F1 racers spend more time turning than level, turning wins.

Justin’s SR-1.1

Given the Snoshoo’s long gestation, Justin’s racer Limitless was bound to get some upgrades and indeed it has, sufficient to earn its SR-1.1 moniker among the Snoshoo cognoscenti.

Most significant of Limitless’ upgrades is a carbon fiber wing. Justin first thought to build the original wood wing, then he heard of the updated wood wing without the rear spar carry-through and he figured his wing search was over. But “then it all spirals.” Craig Catto mentioned he had a better, carbon wing design from the celebrated Paulo Iscold, and Justin had to tell himself to consider changing his mind yet again. He flew out to Craig’s shop in Jackson, California, to see for himself and decided, “Yeah, I want to fly that wing.”

There’s little wonder as the new panel is one of the more modern F1 wings extant. Originally designed by Iscold for Jim Jordan’s Miss Min F1 racer in 2014, the carbon wing incorporates Iscold’s tweaks for a less aggressive stall, and with the molds available at Catto’s building, a new copy would be relatively quick. In Justin’s case, he spent an enjoyable two months at Catto’s shop building the one-piece wing alongside the master. His is the second wing from those molds; a total of four have been built to date.

Iscold reports the wing uses the popular NLF0414F profile from the NASA library, a shape used on many airplanes, but curiously never in its pure, as-designed form. Various designers apply their own small tweaks to suit their needs, including Jon Sharp’s Nemesis racers, Lancair Legacys and Iscold’s own Anequim record setter, among others. For Limitless Iscold de-cambered the airfoil’s center to let it fly at a lower coefficient of lift and applied a set of swirls to the leading edge to allow airflow to remain attached longer at high angles of attack. Both changes soften the stall to make a safer wing, following Justin’s philosophy of a competitive race plane that could be sport flown.

As Iscold put it, “I can make a faster wing, yes. But not safer.” He goes on to note that eking out the ultimate characteristics, often at great cost or risk, is not the winning formula. “To win a race is not a one thing. It’s not one thing on your airplane, it’s the combination. It’s all about the team; it’s the teamwork inside the airplane.”

Unchanged is the airfoil’s somewhat meaty 14.2% thickness, which gives less induced drag in the turns at a small cost in straight and level speed. As the F1 racers spend as much time turning as anything else on their tight 5-kilometer course, reduced induced drag wins the compromise. For details on constructing this type of wing, see many of Eric Stewart’s articles in KITPLANES®.

Once Justin got the wing home to Texas, he opted to build a carbon tail group for Limitless, engendering another sojourn to Catto’s, this time for six weeks. The work was going well, but then, said Justin, “We see smoke…a long way away. That evening they were evacuating the house and then it burned down. His brother’s house burned down, too and so now, we’re all at the shop. [Craig] went and bought an RV.”

So, thanks to California’s never-ending wildfire season, Justin’s reasonable expectation was shop work would halt for months as the Cattos reassembled their lives. But Craig wouldn’t hear of stopping work, saying, “No, we’ll still work on your stuff!” Justin asked again just to make sure, but despite the huge challenges, Catto and crew could not have been more hospitable or dedicated to taking care of their customers. “It was crazy…such a cool family!”

In the fuselage the SR-1.1 incorporates a longer cowling to use an 8-inch propeller extension; the engine cheek fairings are tapered to terminate right at the leading edge of the wing and the overall lines are curved from the nose to the tail, with elimination of fabric covering on the aft fuselage. Instead, a composite fuselage skin is laid over the fuselage tubing to deliver smooth, bump-free streamlining.

Compared to the wing, which was built completely in Catto’s shop, Justin’s fuselage truss is one well-traveled weldment. It took shape in the Snoshoo jigs at A. J. Smith’s shop in Atkinson, Nebraska; Justin then took it to his Texas shop, followed by the tail group from Catto’s and ultimately running all the systems, controls and finishing bits back in Texas. Ultimately the fuselage was covered in its custom carbon fiber skins, these brought forth mainly by Jon Latall and Van Meter.

Deciding they’d make a female mold for future Snoshoos, Jon went to the local Menards and “bought a giant stack of pink foam.” Instead of building on the fuselage, Justin took advantage of a CNC Laser he has access to and cut out a wood template of the fuselage. The foam was glued to wood and “then all the sanding happened,” as the pink foam was grated and sanded into shape, primed, painted, Bondo’d and top coated to form a male plug and finally, the female mold around it. Once the mold was ready, A. J. Smith, Alan, Jon and Justin laid up the carbon fiber fuselage skins and from there it was a seemingly endless process of mounting, dismounting, adjusting and remounting the skins until the desired fit was reached. “It’s a long process,” Jon noted with a certain amount of fatigue in his voice.

Naturally, with the hard work of building the fuselage skin molds behind them, the Snoshoo consortium notes it wouldn’t be difficult to make more skins. “It’s not close enough to call it a kit, but one could be built,” notes Jon. Anyone with an interest should confer with A. J. Smith at Van Meter Smith Racing (VSR) who holds the Snoshoo rights; given the fuselage jig, wing and skin molds, more airplanes could definitely be built with minimal effort by plansbuilt standards.

Engine

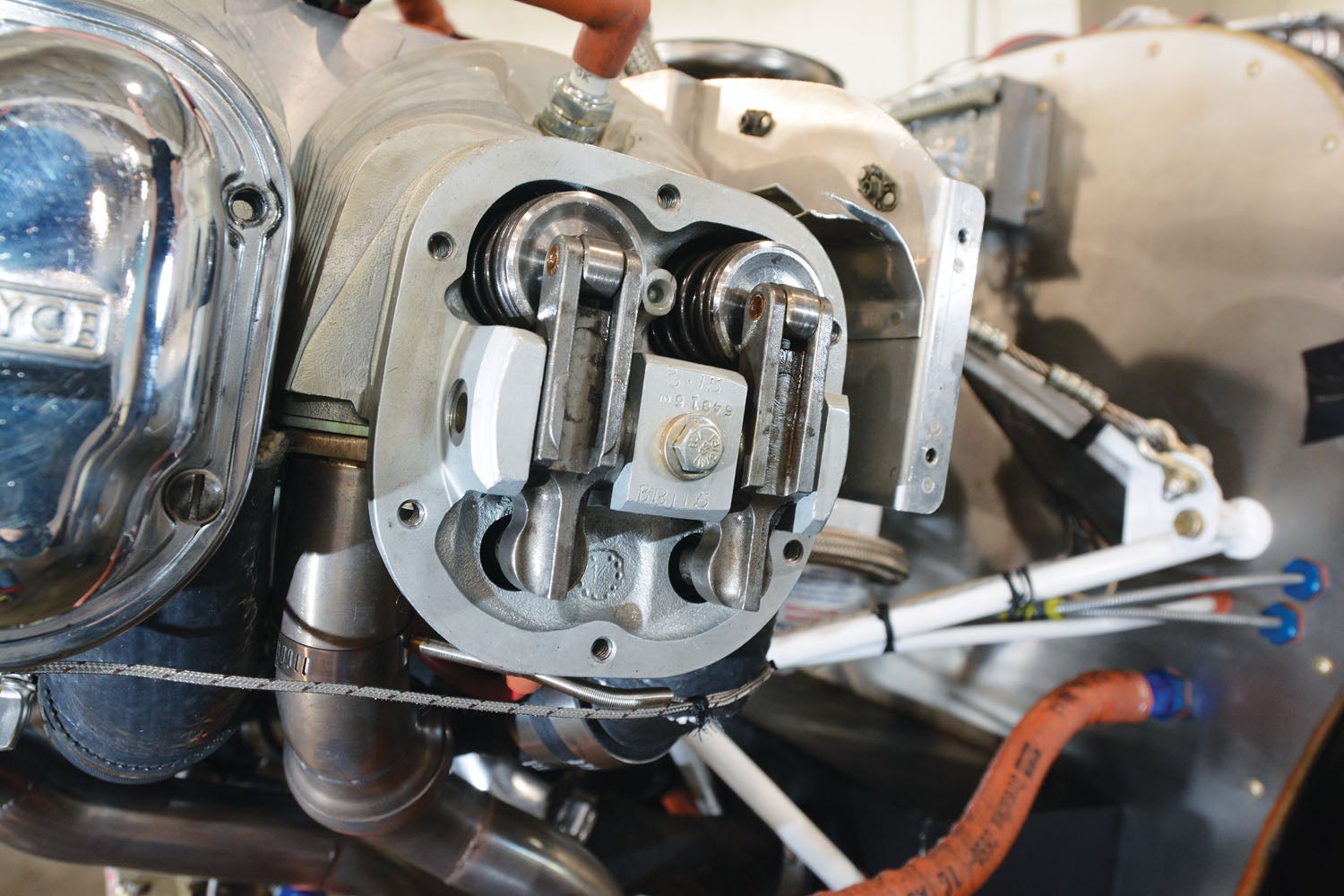

In a display of intelligent risk and fiscal management, along with good testing protocol, Justin first installed a stock O-200 Continental in Limitless. Only after approximately 40 hours of flight testing did he swap in a hot rodded version to open the envelope and in preparation for racing. Justin builds his own engines, which keeps the cost down, which in turn enabled his two-engine approach to sorting out his racer.

Typical of F1, Limitless runs a total-loss electrical system—no charging—but still has all the amenities, including a Light Speed electronic ignition, EFIS, radio and even a starter. The team simply has to keep ahead of charging the ship’s battery between flights, which isn’t all that demanding, as the airplane pretty much flies only from its home base or well-supported Reno outpost.

An electrical standout, says Justin, is the quality of the radio. Often Formula 1s make do with sketchy communications built around a handheld radio, some patched-in cables and many good wishes about antenna efficiency, noise cancellation and all that. Because Limitless has a composite tail skinned in fiberglass, Justin was able to hide a proper com antenna in the vertical tail; it’s plugged in to a compact MGL panel-mount radio and works really well. Justin reports being able to conduct conversations during pilot qualification flights, “unheard of” in the F1 pits, he says.

For his race engine Justin concentrated on basics, ensuring good cylinder seal to “make a good pump” and fussing the moving parts balance to zero tolerance for reduced energy-wasting vibration. He works with a local machine shop for the precision whittling but otherwise does all other engine work himself, a skill acquired working alongside his stepdad and during his motorcycle racing days.

One advantage of running a starter—definitely a luxury in the traditional F1 mindset—is the practicality of running more than two propeller blades. Limitless has worn both two- and three-blade props and the jury is still out on which is better. “I honestly don’t know anymore,” he says in exasperation. “I just call Craig and say this is what it’s doing, what do we have to do?”

Justin has worked exclusively with Catto on props, the team trying a three-blade toothpick in 2018 and 2019, but reverting to a two-blade in 2021 (there was no racing in 2020 due to the pandemic). After noting the blade profiles differ between the two- and three-blade versions, Justin was mum on the relative advantages of the props, likely because they are so close it’s hard to tell, along with not wanting to give away any secrets. At the 2021 races he was thinking about going back to the three-blade, but the two-blade was working so well he stuck with it.

Justin’s bottom line on F1 props seems focused on the class’s standing starts. “This race, to me, is not won on the ground, but it is lost on the ground if you don’t have the right prop. I want the best of everything with the three-blade…[and I] may go back to a three-blade, an upgraded one, a different one.” Like we said, the jury is still out on propeller design and likely will be for a very long time.

As for engine/propeller rpm, “4500 rpm is max rpm; you’re getting everything you need to get out of it…[and it] sounds really good too, which is part of the appeal.”

Hand Controls

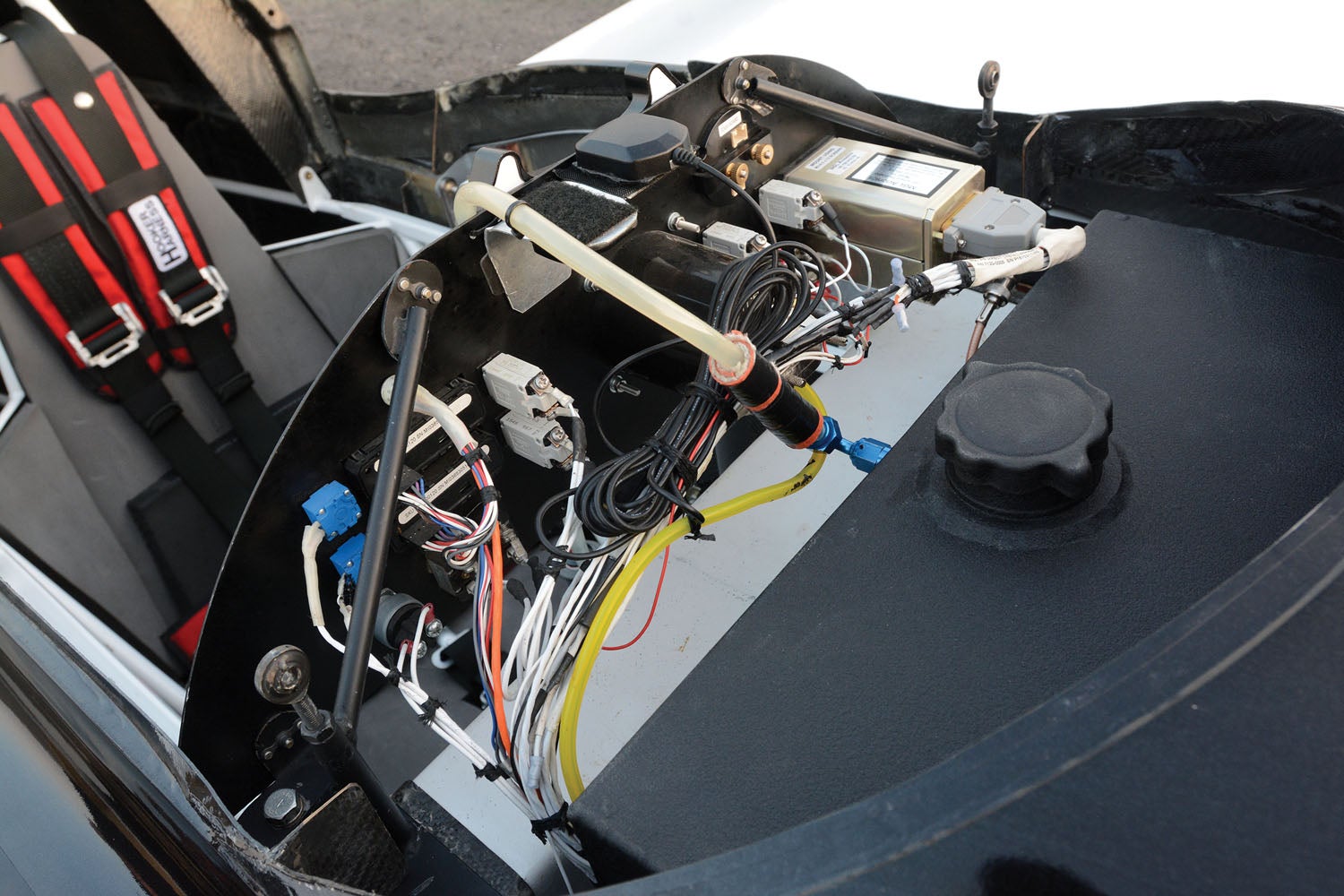

Justin, Van Meter and especially Jon Latall have all been involved in developing Justin’s hand controls starting with the Citabria Justin got his private training in. They took that first design and moved it to Quadnickel in 2016. Unlike the Citabria, all conventional rudder controls were removed from Quadnickel, and Limitless doesn’t have any rudder pedals either. The reason is Justin’s long legs—he’s a thin, leggy 6 feet, 4 inches tall—and every inch of legroom is needed in the tiny F1 cockpits. Eliminating the rudder pedals gave him the needed room.

On the other hand, Justin’s Kitfox retains its rudder pedals so conventional pilots can fly it. That doesn’t apply to Limitless. “No one else can fly it,” says Justin. “Phillip Goforth tried to fly it, but taxied it 10 feet and said no way! He’s a hell of a pilot, a great stick and rudder guy…he grew up bush flying in Alaska [but couldn’t adapt to the hand controls].” For Justin, though, the hand controls are home, and he does a great job with them.

That was a good thing when Justin had his first hop in Quadnickel. It was Justin’s first time in a single-seat airplane and an F1 at that. The taxi to takeoff was a long, hot affair, followed by a two-ship formation takeoff with Goforth next door. Seconds after takeoff the engine quit cold and Justin remembers thinking, “Guess I’m going to learn how to land this right now.” Luckily he was on a hugely long runway. The touchdown was good, the tracking straight, and in the end Justin’s worry was he couldn’t clear the runway; there were a bunch of people behind him trying to take off. But that’s small stuff after an engine out! The problem turned out to be fuel venting where the curve in the fuel line was upside down.

As for the controls in Limitless, there is a conventional stick, which operates completely normally and is held in the right hand. A second stick—the yaw stick—is provided for the left hand. Moving the yaw stick forward gives right rudder, aft gives left rudder. Additionally, it has a twist grip off of a motorcycle for the throttle, and jutting straight up from the stick is the vernier mixture control. Justin jokingly calls this busy bit of kit the “pseudo collective.”

Braking is activated by motorcycle hand levers, one on each stick. In fact, the design is essentially HOTAS in mil-speak, as Justin’s hands never need leave the sticks except to change radio frequencies.

The yaw stick is all cable-operated, with conventional rudder cables running forward from the rudder until inside the fuselage, then both cables are guided to the left to run to the yaw stick on the left side of the cockpit. An adjustable cam at the base of the yaw stick gives the desired feel and responsiveness Justin was used to with the Citabria. Justin says Limitless yields “the same hand movements I was used to in other airplanes.” The elevator “is pitch sensitive but not terrible…yaw is pretty sensitive.” Control efforts are “extremely light,” to the point where Justin finds just the weight of his arm is sufficient rudder trim, where in a conventional arrangement the pilot easily tires from pushing one or the other rudder pedal. Also, the full-power standing starts in F1 typically cause leg fatigue in conventional airplanes from holding the brakes, whereas Justin says he can easily hold Limitless “all day long with just one finger.”

We asked about control harmony and Justin says, “It’s second nature between the two sticks. I don’t even think about it anymore.” That tells us the harmony is pretty good. He did say there was a notched learning curve when transitioning from tricycle to tailwheel hand controls during his Citabria days. Finally the instructor told him to quit thinking about it and just do it, and that was the turning point. “After a few hours I just needed to understand I knew what I was doing and to quit thinking about it and just do it. That really helped out a lot.”

Testing

With a new airplane, unique flight controls and the unforgiving nature of winning a once-a-year race as the goal, thoroughly testing the new Limitless was a must. As Justin put it, “The brain trust had me expanding the envelope in steps.” He taxied it first with no squawks and then what sort of first flight to perform became the question. “The first flight had a narrow window, and did I want to do a hop or go around the pattern? I’ll hop it,” said Justin.

For sure a part of the hop decision was electing to make the first flight at the generously long 9300-foot runway at Big Spring in West Texas. This engendered a 225-mile one-way tow for the first flight, but the long runway, along with longtime friend and fellow F1 racer Phillip Goforth’s hangar at Big Spring, made it a relatively easy decision. In fact, Goforth’s hospitality meant more than just the first flight could be done at Big Spring.

With the brief straight flight successfully completed, Justin taxied back and didn’t attempt a full first flight until the next day, when he made a single flight of about a half-hour. The result was a one-washer change under each side of the horizontal stabilizer that the team didn’t even bother with until after the first 15 hours of flying. “We hit it pretty close,” as Justin dryly put it. No changes in roll or yaw were needed, and once the pitch trim was set the airframe was essentially ready to go.

Once Limitless was a known flying airplane, testing became a slow expansion of the envelope, with the brain trust setting specific target speeds and attitudes to expand the envelope. As expected, the airplane proved increasingly stable with speed, and at the other end Justin began with a target touchdown speed of 105 mph (they were still on the long runway), with Justin slowing the approach as he gained confidence. He reports Limitless glides like a sailplane, a common remark with aerodynamically svelte and featherweight F1 race planes. He eventually settled on a 95-mph approach speed. That’s slow enough yet with a reserve. “I typically slip all the way in so I can take it out and have energy right now.” By the time testing was over, Limitless went from earning its airworthiness in January to winning in Reno the next September.

Making It Race Ready

Save for the reality that few projects—and absolutely no racing machines—are ever finalized, the last steps before trailering Limitless to Reno in 2018 for its debut race and what turned out to be its debut win were the installation of intersection fairings and the final surface finishes. Most involved of these were the wing-to-fuselage fairings, followed by the vertical tail and wheel pants. Just before Reno the fuselage was vinyl wrapped. As an expedient, the sponsor’s logos were added on top of the base wrap, but in the future the logos will be incorporated into the main wrap, thus saving numerous exposed edges. Of such things race wins are made.

All told, Limitless saw close to 60 hours of testing before arriving at Reno, all of it accomplished in nine months of intensive testing and improvement. Given its impressive win record, the effort has been worth it. For Justin it brings up all the people who have helped put him in the winner’s circle twice to date. “The people involved in the project…that’s the major part of it. There were a lot of nights I was in the shop working on the plane by myself, but not a day went by when I didn’t at least talk to one of the brain trust.” It’s also been a dedication to excellence. Justin was particular on how parts fit. “I threw a lot of parts away. There was a lot of design time too, sitting by the computer with a CAD program going. It’s a game of ounces.”

Really enjoyed reading this, Tom. Great write-up.

Looking forward to seeing where Justin goes next.