I was caught off guard by the sight of familiar aircraft in the Sonex Aircraft flight center. “How?” you wonder. I’ll explain. I’m often at Sonex Aircraft during non-business hours to tend to work or personal matters—borrowing a cup of bending brake, for example—and go directly to the task at hand. One day, instead of charging headlong through the flight center to the shop, I paused among the shadows and silence that engulfed the factory aircraft. On work days, the hangar is brightly lit and abuzz with whining air tools, chugging air compressors, aluminum howling at the slash of a blade and music ranging from Sinatra to ScHoolboy Q resonating off the metal walls and ceiling. On that afternoon, the silence and subdued light in the hangar suspended my familiarity with the setting and I saw the aircraft with the fresh excitement expressed by visitors. “These are cool.”

I had a similar experience a few weeks earlier at a Barnes and Noble. After standing up from browsing a home magazine, I came face-to-face with the electric Xenos on the cover of KITPLANES®. I had already seen the issue in my mailbox, but I wasn’t expecting to see it there. KITPLANES® is never snuggled up to model trains and plastic airplanes; it is always by the boat and car magazines where it sometimes hides behind other aviation titles and must be sought. I was also caught off guard because, in that moment, I wasn’t expecting to see a product I know so well. For a few brief moments, I saw the Xenos through the eyes of a stranger. As the surprise wore off, pride settled in. Pride that I work for a company whose products grace the covers of enthusiast magazines on newsstands.

Let’s Keep Moving, More To See

A few weeks later, as I again passed through the Sonex Aircraft flight center, I noticed a coworker had installed the windshield on his Sonex-B project. That stopped me in my tracks like the cover of KITPLANES® had weeks earlier, and the Sonex Aircraft factory aircraft had before that. It was a sign of progress. One that helps define the shape of the aircraft. One that separates the inside of the airplane from the outside. It struck me as a no-turning-back moment in his project, equal to hanging the engine or getting it on its gear. It is a moment to celebrate.

I’m sure as he fit the windshield he wasn’t celebrating—he was focused on drilling each hole, on trimming each edge and on getting it to lie flat on the firewall former. He was thinking how he didn’t want to scratch the soft-but-strong polycarbonate. The idea he was building an airplane was probably far from his mind; it was lost in the minutiae of the tools, techniques and materials. He wasn’t building an airplane at that moment, he was fitting a piece of plastic to an aluminum structure. After the windshield was fit, his mind was released to think about the next step. There is always a next step to crowd out the accomplishment of the last. The to-do list is ever visible in the unfinished tasks while the finished tasks hide in plain sight.

When I built Metal Illness, I was absorbed in the literal and metaphorical nuts and bolts of the project. I focused on each dimension, each cut and each bend angle. My thoughts were focused on drilling each hole, deburring each rough edge, routing each wire and filling each pinhole in my position-light fairings. I fretted over imperfections that, trust me on this, get absorbed by the entirety of the airplane and vanish from sight like a single blade of grass on an expansive lawn.

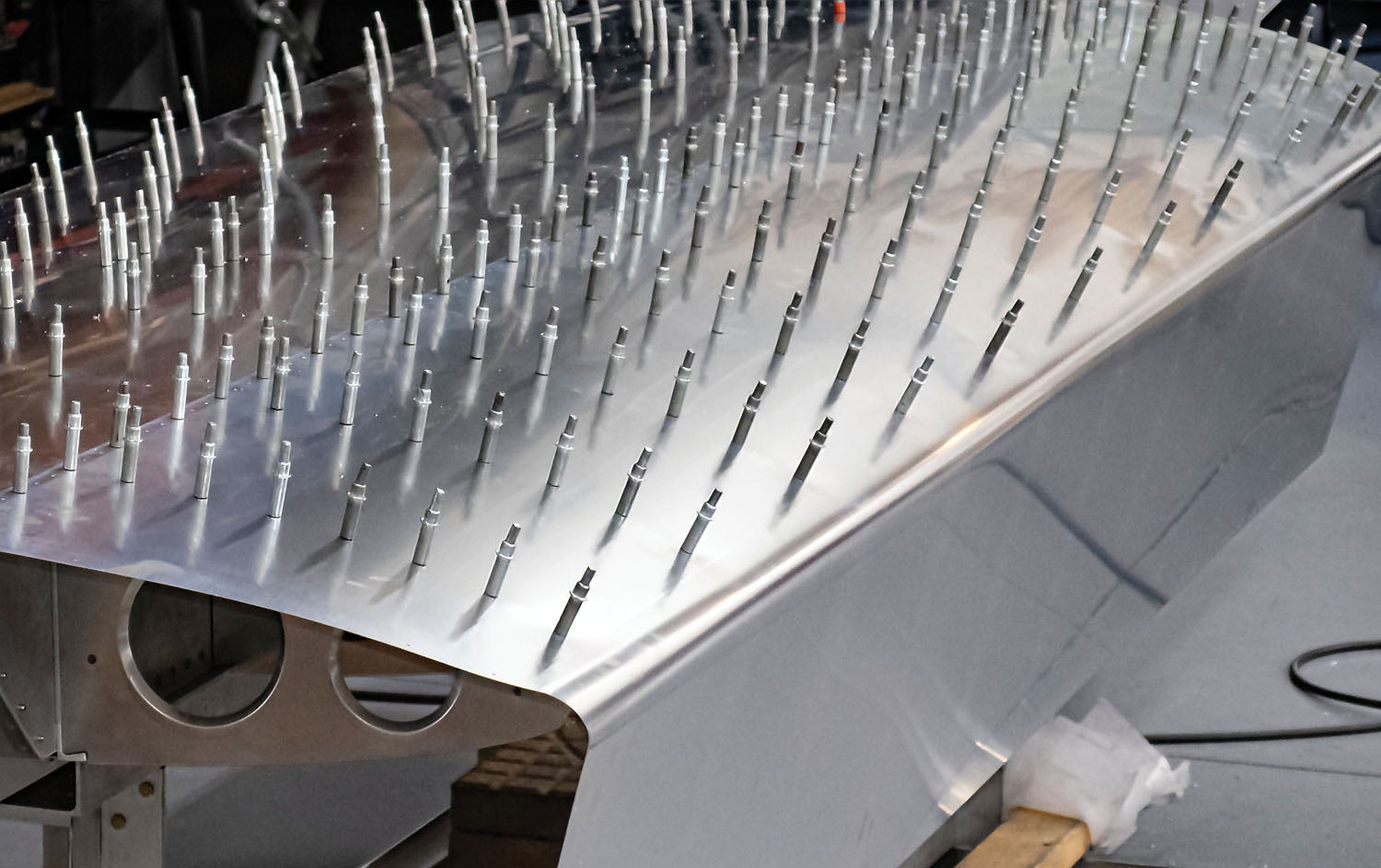

Seldom did I see my growing assembly of aluminum bits as an airplane. Seldom did I notice my progress. Building Metal Illness was an ongoing series of small, often boring, tasks, like deburring rivet holes in a wing skin for two hours—a task that produced sore feet and a backache but no appreciable signs of progress.

Even fitting the horizontal stabilizer to the fuselage was experienced as a series of small tasks—square the tail to the fuselage; clamp it so the clamps aren’t in the way of drilling holes; double-check the tail’s position; triple-check the tail’s position; step-drill the bolt holes; deburr the holes; install the bolts; check the tail’s position one last time. With that done, I moved on to what came next. Like a guided tour, there was little time given to absorb the moment or the place. “This is the room where Elvis Presley recorded ‘That’s All Right,’ and rock and roll was born. Let’s keep moving, people. There’s much more to see.”

Green Beans on Game Day

I’ve said this before, and I stand by it: The only reason to build an airplane is because you want to build an airplane. It’s a huge undertaking. Progress can seem immeasurable at times, which can be discouraging. (As I wrote that I recalled every time I’ve driven or flown the length of Illinois. It’s a huge undertaking. Progress can seem immeasurable at times, which can be discouraging.) Aluminum airframes are born more from hours of mundane drilling and deburring than they are from quick-but-satisfying minutes of riveting. Progress on composite aircraft hides within clouds of micro-balloon dust from unending hours of filling and sanding. Tube and fabric aircraft gestate slowly during hours of fish-mouthing tubes and stitching fabric to ribs. Enthusiasm can wane when the individual tasks crowd out the accomplishments.

I’ve also written that building with tunnel vision can reduce large tasks into many small ones. It’s important to be mentally present for the individual tasks, but it is equally important to notice your progress. If you only look through the tunnel, you won’t see the achievements that hide behind the completion of the individual tasks. Those achievements sometimes need to be sought to be appreciated. Occasionally, if you’re lucky, your progress will startle you. Your thoughts may be on your team’s impending kickoff as you enter your garage to retrieve leftover green bean casserole from the garage refrigerator. As you do, the silhouette of an airplane surprises you. You see your project as an airplane, not a task. Should that happen, miss the kickoff and absorb the moment. It’s worth it.

In music, the silence between each note is as important as the notes themselves. In homebuilding, the time between tasks is a time to recognize your progress. When you finish a work session, pause to absorb your accomplishment, both the totality of what’s been accomplished and what you accomplished during that single work session. A wing skin looks no different after two hours of deburring rivet holes, but that two hours unlocked the next 20 minutes when rivets will secure the skin to the ribs and spars. Try to suspend your familiarity with your project and see it through the eyes of a stranger, a stranger who would be impressed. “Do I see airplane wings in your garage? That is so cool!” It is never too early or too late in a project to notice and take pride in your progress. You’re filling your garage with an airplane. Most are filled with the stuff of suburbia.

well written ,good subject, good writer