Get it out of your system now. Mock this XCub’s distinguishing feature. Ask if you can get it without the training wheel. Remind us all that Piper did this once and the result was an airplane so unlovely that they built the Cherokee (or maybe it was the Comanche) as an apology. Proclaim to everyone within earshot that the only real Cub, the only real bush plane has the third wheel back at the tail, where Steve Wittman, Dick VanGrunsven and every other aviation pioneer said it had to be. Fold your arms, huff away home in your hybrid-electric car with antilock brakes, air bags and traction control.

Get it out of your system now. Mock this XCub’s distinguishing feature. Ask if you can get it without the training wheel. Remind us all that Piper did this once and the result was an airplane so unlovely that they built the Cherokee (or maybe it was the Comanche) as an apology. Proclaim to everyone within earshot that the only real Cub, the only real bush plane has the third wheel back at the tail, where Steve Wittman, Dick VanGrunsven and every other aviation pioneer said it had to be. Fold your arms, huff away home in your hybrid-electric car with antilock brakes, air bags and traction control.

Good, now we can talk. The only thing culturally remarkable about the CubCrafters nosewheel-equipped XCub—which I’ll contract to NXCub hereafter, though, technically it’s an XCub with the optional gear arrangement—is that the company has the smarts and courage to build it. The world in 2020 is radically different than it was in 1950, when new pilots started in Cubs (or Cub-like aircraft, such as the Taylorcraft, Luscombe and the Cessna 120/140). Then you could understand why tailwheels were the “conventional” gear. These pilots moved up the ranks to the Cessna 170 or Piper Pacer, and if they were lucky would find themselves in the Cessna 180. All the best airplanes had tailwheels, steaks were still good for you and all was right with the world.

Of course, this mindset ignores that Beechcraft had the tri-gear Bonanza in the late 1940s, that the military had already turned to tricycle-style landing gear in fighters and that few commercial aircraft would be designed with anything but the big tire up front since the 1950s. Still, the mystique of the taildragger persists, and there are arguments for the design being more rugged, lighter and more demanding of the pilot in a good way—keeps you on your toes, so to speak.

CubCrafters’ Take

Few companies appreciate the desire and need for a strong tailwheel airplane better than CubCrafters. Jim Richmond’s company has, since 1980, been fixing Cubs, providing upgrades to Cubs, then building new all-new Cubs. Which, in turn, led to a relentless pursuit of a better Cub, first appearing as the LSA-capable Carbon Cub and then as the heavier, more capable (but no longer LSA) XCub. Both of these are offered as factory built as well as Experimental/Amateur-Built using a customer-assistance program at the Yakima, Washington, factory. The Carbon Cub is actually three in one: the SS factory-built LSA, the EX kit and the FX Experimental with builder assist at the factory.

The NXCub was the result of substantial surveys of buyers and potential buyers of the XCub. They were clear in what they wanted from an “alternative” XCub: a powerful, easy-to-fly design that would not require them to bone up on their tailwheel skills or make it necessary to get a tailwheel endorsement. They were also aware of the cost differential in insurance; a low-time tailwheel pilot in a $400K airplane can make for some breathtaking insurance premiums. But those buyers also did not want a “beginner’s” backwoods airplane or one so compromised by the nosewheel that it wouldn’t really be durable and safe in the backcountry. According to CubCrafters’ own data, these buyers wanted an airplane with the full potential of a tailwheel version, not just “80 or 90%.”

The company laid out a number of objectives for the NXCub. First of all it had to be fun and easy to fly—this despite packing quite a bit of power, 215 hp from a very special CC393i engine that’s based on the Lycoming IO-390—and “stress-free” to fly, which gets back to the nosewheel configuration for the bulk of today’s pilots. It had to be strong enough to deal with unimproved strips, and the goal here was not just an airplane that would tolerate gravel and grass and rough strips, but actually thrive there. Understanding that some of their customers would be totally new to the utility end of the market, CubCrafters felt compelled to add a huge amount of “ruggedness margin” to the design. I’ll get to that in a minute.

Finally, CubCrafters wanted the airplane to be respectably fast, again an acknowledgement that some buyers would be coming from traditionally faster designs and would not want to “downshift” to a 100-mph cruise in order to get the short-field capabilities. Perhaps most surprisingly, CubCrafters says the NXCub is actually faster in cruise than the tailwheel version, something unlikely to set well with the traditionalists out there.

How Did We Get Here?

If you haven’t been watching CubCrafters’ work, you might not be familiar with the underlying XCub. Yes, it looks like Piper’s venerable bush plane, but only through very dirty glasses after an all-nighter riveting on your horizontal stabilizer. Yes it has a high, strut-braced wing with a constant-chord airfoil, two seats one in front of the other and fabric surrounding both the wing structure and the steel-tube fuselage structure. That you recognize as Cub. But there’s a ton of carbon fiber—OK, maybe just a few pounds, as weight savings is the goal—throughout the airframe, from the shapely cowling to the bows that form the rounded shape of the wing tips, rudder and horizontal tail.

Inside the wing is a metal spar and delicate-looking aluminum ribs with many CNC-machined parts to reduce both the total number of pieces and their aggregate weight. Changes to the steel-tube frame include additions for both gear types, meaning that any given XCub can be either tri-gear or taildragger. In fact, cover plates conceal where the “missing” gear would be fitted, so changing in the field requires no modification of the fabric fuselage covering. All pieces for the tailwheel are there, and the nosewheel structure bolts to the engine mount right at the airframe junction, so loads are sent to the fuselage cage, not the firewall itself. Not only does this make the XCub easier to manage from a production standpoint, but it gives both first and subsequent owners enough choice to protect the value of either model.

Developing the nosewheel structure is a story in and of itself, and consumed a tremendous amount of R&D effort on CubCrafters’ part. The system is based on a massive vertical strut with an integral shock mechanism. It’s a free-castering design with a seriously robust trailing link. The benefit here is that the nosewheel acts like it has a much greater diameter, rolling over terrain more easily. (Ever wonder why dirt motorcycles have big front wheels and street bikes do not? This is why.) Even then, the nose gear carries a big tire: an 8.00×6 with a 20-inch outer diameter. We’re not talking a 6.00×6 skateboard tire here! As CubCrafters’ Brad Damm says, “This was designed from the outset to be a serious backcountry airplane.”

There’s a clever mechanism that allows you to disconnect the steering stops by pulling a pin and dropping a key away, which would allow the wheel to rotate through 360°, in turn making parking of the airplane easier inside a crowded hangar. (The normal limit is 95° in each direction.) You can push the airplane straight back without having to fight the geometry. Anyone who has tried to keep a free-castering nosewheel straight without using a tow bar appreciates this. The outsized nosewheel is joined by Alaskan Bushweel 26×12 tundra tires.

CubCrafters rightly points out that the NXCub has better visibility on the ground than the taildragger version, which is actually quite good by those standards, and the ride is plush even over really quite lumpy runway surfaces. But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

Under the Hood

It’s worth reviewing a few more differences between the XCub and its predecessors. While the “cheeky” cowling is similar to others in the lineup, it hides a thoroughly revised and updated version of the angle-valve IO-390 that’s exclusive to the NXCub. Thanks to a specially designed cold-air induction system rendered in magnesium, as well as an accessory case and oil sump in that lightweight material, the engine lost a fair bit of weight. In place of mags are dual Lycoming EIS electronic ignitions and the lightest possible alternator and starter are used. In addition, CubCrafters fits all XCubs with carbon-fiber baffling, a lightweight four-into-four exhaust system and other detail upgrades to get the whole package to within 10 pounds of a parallel-valve engine package that provides less power.

Further up front, there are choices in Hartzell composite props. The two-blader is a 76-inch diameter Trailblazer, with the three-blade Pathfinder model optional. Both are shrouded by a carbon-fiber spinner. Any doubt about how much power is getting put into thrust by that Hartzell should be dispelled by the pie-plate-sized intakes up front, with a clever smile-shaped cold-air inlet system below the spinner, in addition to lower side gills and a generous bottom cowling exit. (The XCub does not have pilot-adjustable cowl flaps, and, based on my flights, doesn’t appear to need them.)

Flying the Thing

Brad Damm and I saddled up one of the factory NXCubs for some flying out of the company headquarters in Yakima, Washington. The factory is busy and much larger than the last time I visited, which, admittedly, was several years ago. The NXCub is actually quite imposing as you approach, standing tall on big wheels. A quick walkaround reveals just a few of the detail refinements on the airplane, including the aileron controls (pushrods) hidden inside the rearmost struts, a number of fairings on the strut intersections—though there are still flying wires under the horizontal stab—and new ailerons. Introduced with the XCub, these G-series ailerons are all aluminum (as are the flaps) and are aerodynamically balanced with a generous slot between the wing and the leading edge of the flap and blunt trailing edge. CubCrafters wanted the XCub to have well-balanced controls, which the original Cub did not, especially at higher speeds.

The flaps are also different, also G-series items on the NXCub. With a 1.5-inch-lower hinge point, these simple flaps (they are not pure Fowler-style where they slide back as well as tilt), have very good authority and, similarly, a generous gap to the back of the wing in an effort to keep airflow attached to the top surface. They’re operated by a bar pivoting near the left-side windshield header, and each setting offers something different: position one is for lift, two starts to add drag and full flaps are all about turning the NXCub into a barn door. Full-span vortex generators help keep the airflow moving across the wing, permitting some fairly outrageous angles of attack without the houses getting bigger. (Unless you want them to.)

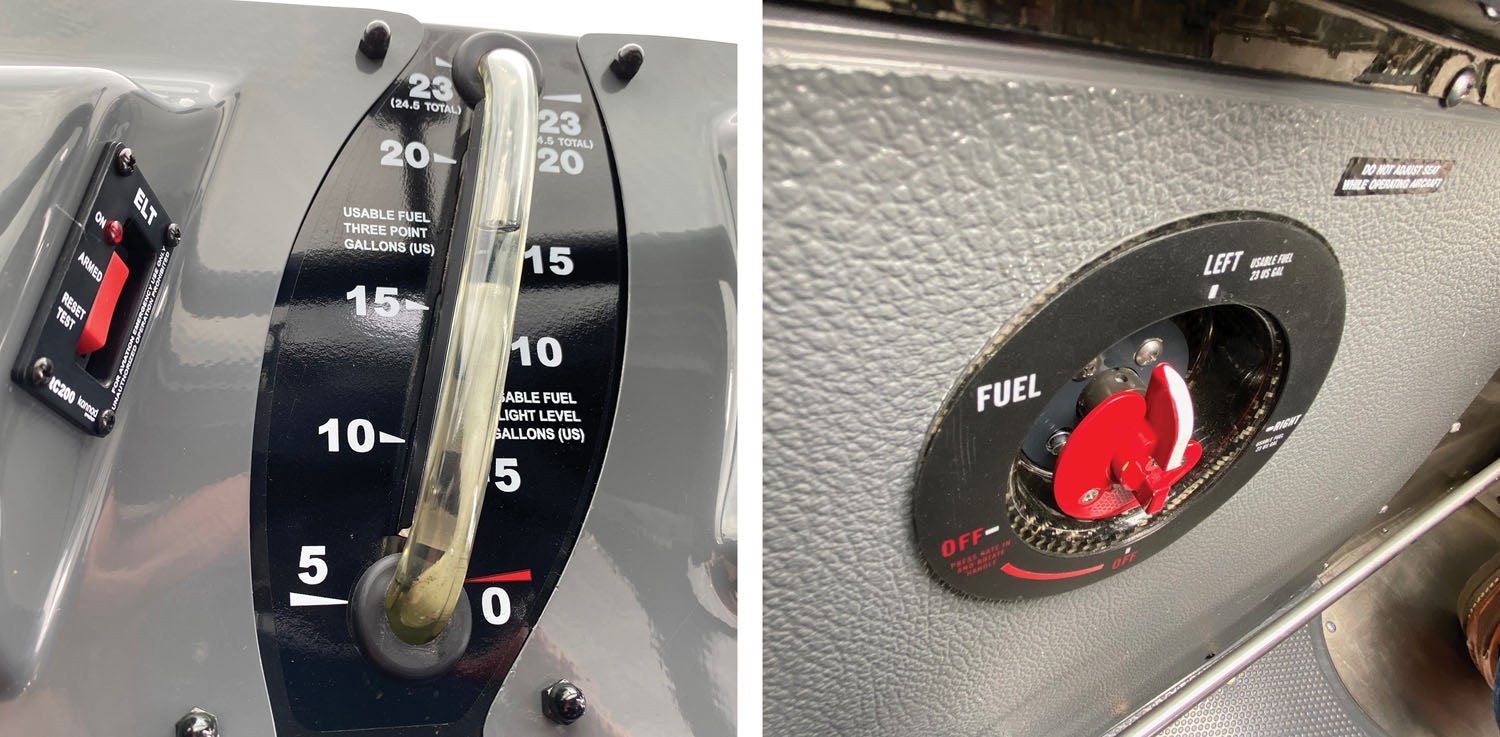

I climbed up front and couldn’t help but be impressed with the NXCub’s top-line interior, two leather seats, carbon accents and a really obvious attention to detail. The airplane I flew had the optional Garmin G3X Touch package with autopilot, and backup G5 EFIS. The NXCub is set up for right-hand stick, so the throttle and prop levers are on the left sidewall (the mixture’s on the panel) with the flap lever overhead and the fuel selector just outside your left thigh. The stick has a trim switch, autopilot disconnect and push to talk. The panel is well laid out. I was comfortable after just a few minutes.

How’s She Go?

Finally after a bit of chatter, Brad and I got to Yakima’s main runway and pushed off into very little wind. The procedure is simple. With the runup complete and two notches of flaps selected, we turned onto the runway. I should note that we had just 20 gallons of fuel aboard (max is just shy of 50) and no luggage. With less than 400 pounds of human cargo aboard, we were around 450 pounds under the 2300-pound max gross. (The certified version of the XCub is rated in the Normal category to 2300 pounds and 1980 pounds in the Utility category.)

So, do the math. Under 2000 pounds of airplane with 215 hp and a big prop. Roll the throttle open, count to about two and a half. By then, the airspeed has whipped through 40 mph indicated (IAS) and you can hoist the nose. Up it comes as the NXCub accelerates rapidly. It takes quite a bit of deck angle to maintain the best-angle climb rate 59 mph IAS, and as I glanced down we were easily beating the rated climb spec of 1500 feet per minute. It felt like we were almost hovering over the runway, which seemed excessively long by now, by the time I thought to lower the nose and start retracting the flaps. Trees at the end of the runway? No problem.

Departures happen very quickly but here’s the important thing: While the acceleration was brisk, the airplane is marvelously controllable and predictable. At no point did I feel it getting ahead of me or requiring unusual control inputs. The ailerons have a tiny bit of deadband right on center but pick up their effectiveness smoothly and progressively, with little effort at this low speed. It took almost no adjustment for me to get the inputs right to keep the bank angle and rate of change right where I wanted them.

And, as you might expect from a certified aircraft, it was trim-stable in pitch with relatively long stick throws, meaning it was easy to nail the pitch attitude despite power and configuration changes. In yaw, the airplane has clearly benefitted from the added fin area that came with the XCub, and while it is sometimes the case that a nosewheel becomes destabilizing in yaw, I didn’t see any of that. It was a bit bumpy as we crossed the foothills to the south of Yakima, but it was no trouble keeping the ball in the center and the other axes under control.

Brad and I did one landing back at Yakima and it was easy. The airplane wants to approach at about 60 mph IAS, which feels slow but is well within its performance envelope. (How much so I would find out a bit later.) The big prop makes speed management simple and adding the third notch of flaps adds enough drag that you’ll want to carry a little bit of power. But that combination makes it crazy easy to find your spot on the runway and hit it, right on speed, with exactly as much energy as you’d planned. It helps, I suppose, that you can see so easily over the nose and that you can be a little lazy with your feet. (I’m not advocating that but, hey, it happens.)

Short Stuff

On the way over to an 800-foot dirt field the CubCrafters guys use to show off short-field performance, Brad and I did a few performance checks. At high cruise, the airplane will do what they say, about 145 mph true (on 11+ gallons per hour) with a max-level speed of 153 mph TAS. Those are impressive numbers for an airplane with 175 square feet of thick wing and an emphasis on low-speed handling. More likely, owners will fly the airplane at 130-135 mph TAS on less than 10 gph, but that’s still very good range with just short of 50 gallons on board.

In preparation for landing on the farmer’s strip, we did some slow flight—the NXCub is very impressive here, with superb control authority and no tendency I could see to get squirrelly—and a short stall series. I came at it like someone who has never seen the airplane, and so performed a slow entry to a power-off stall; there, the airplane just gains pitch, slows down and eventually just begins to mush with the stall warning blaring. Handled gently, I couldn’t get it to break. Brad took it for a moment and provoked an aggressive accelerated stall straight ahead that eventually showed a full break, but recovery was immediate and, with all that power, recovering from the descent happens promptly.

I try to be gentle with new airplanes so the landings at the dirt strip were not a ton different than on pavement—no drop-it-in gymnastics, in part because the low approach and stall speeds make 800 feet seem generous. Brad did one that had an aggressive roundout, plopping us onto the dirt, followed by full braking. The nose dipped a bit, the tires squirmed—and we were stopped in way less than half the length of the runway. I sat there giggling like a kid. We did a few more and with every one my confidence grew. The low-speed behavior of the NXCub really has to be sampled to be appreciated. And now add in the comfort of the nosewheel—one designed to be abused and capable of handling truly rugged terrain. Impressive.

Kit or Certified?

CubCrafters was spending 2020 wrapping up certification of the NXCub but building Experimental/Amateur-Built versions at its completion center. (There is, strictly speaking, no kit version of the NX or XCub.) The arrangement will be similar to the XCub’s, where the builder comes to the facility for a total of seven working days, focusing on fabrication over routine assembly of components; this includes a sampling of all the materials used, including fabric. The builder returns later to put those pieces together.

Prices? The XCub starts at just over $333,000. The nosewheel option adds $4890 but you must order it with the CC393i engine, which is a $26,870 upcharge. To replicate the airplane I flew, with the high-line avionics, impressive interior, paint scheme and all the other goodies, you’re looking at about $407,000. That cost is the same, whether you buy it built or participate in the construction. Yes, it’s a big number, but the cost reflects the components and the R&D investment, and shows what it takes to bring a design to the top of its form. Truth is, for many pilots who came up in the period after “real” Cubs made taildraggers the everyday airplane, the presence of a nosewheel on an airplane that’s as capable of off-pavement work as the NXCub will make the whole hard to resist. In fact, for many this is probably the backwoods airplane they’ve been waiting for all along.

Not a kit plane.

I did think it was funny that the cover story in this months Kitplanes Magazine had a N/A under kit price and estimated build time. haha

I’m sorry but putting a nose wheel on a cub is like square head lights on a jeep. something is not quite right. If your going to do that, make it a sidexside and call it a Tri-pacer.

No doubt – The insurance companies rule!

Apparently the author hasn’t heard of Zenith, or the Cessna 206? Both popular tri-gear bush planes.

Indeed. The author has.

Then the tag line makes no sense, “Can Cub Crafters Make the tri-gear bush plane a thing?” It’s been a thing for decades. The real question is can they sell it to the Cub fans?