Every amateur-built airplane tells a story about its creator, and the most interesting are the result of dissonant prognostication, attributes seemingly in conflict. With its bright purple cowl and sunshine spinner, a bare metal Zenith Cruzer stands out in the regimented grid of the homebuilt campground at EAA AirVenture. Its story doesn’t get interesting until you are nose-to-nose with the goggle-eyed Minion windshield shade.

Every amateur-built airplane tells a story about its creator, and the most interesting are the result of dissonant prognostication, attributes seemingly in conflict. With its bright purple cowl and sunshine spinner, a bare metal Zenith Cruzer stands out in the regimented grid of the homebuilt campground at EAA AirVenture. Its story doesn’t get interesting until you are nose-to-nose with the goggle-eyed Minion windshield shade.

Introduced at Sun ’n Fun 2013, Zenith Aircraft’s Cruzer is the speedy, cross-country cousin of its light-sport utility airplane, the STOL CH 750. They share the same two side-by-side seats, but a single strut supports the Cruzer’s wings, which don’t wear the STOL’s leading-edge slats. Walk around and you’ll discover a vertical fin and rudder rather than an all-moving yaw control and a clipped-span horizontal stabilizer with a symmetrical airfoil. Tiny 5.00×5 rollers wear streamlined spats.

So why does this Cruzer stand tall on three large, naked rubber donuts?

Stickers on its bare metal offer some clues. Behind the pilot’s door is the large logo of the Recreational Aviation Foundation, a group dedicated to protecting, preserving, and promoting recreational backcountry airstrips. Another sticker suggests that KBJC, the Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport, is the Cruzer’s home.

On the vertical fin, a sticker with Colorado’s sunny C logo nestled in the mountains supports the airplane’s home state. Above it is the black silhouette of a winged dragon. Or maybe it is a stylized Phoenix, the name of the endlessly reborn bird spelled out in yellow-trimmed purple letters just aft of the cowl and above a sticker for ULPower.

The prop card confirmed these prognostications and connected me to the Cruzer’s creator, Gary Motley, to explain its dissonance.

Subjective STOL

Motley is an avuncular registered nurse who, after 15 years in the ER and ICU, moved to Colorado in 1993, where he’s provided metropolitan Denver with home healthcare for the past quarter century. And he’s adapted to the mile-high performance penalties.

Zenith says a 1320-pound light-sport Cruzer needs 350 feet to take off and land. At sea level, with 75-percent power, it cruises at 118 mph. At the same weight, the STOL CH 750 needs 100 feet to take off, 125 feet to land, and its maximum cruise speed is 100 mph. “Up here, with two people, full fuel, and 6,000-foot density altitude, I’m usually off in 800 feet or less,” said Motley. “I consider that STOL. It’s as good as the Maule I had. All homebuilts are individualized. I wanted a utility airplane that meets my needs; that’s why I have big wheels and an autopilot. It has no idiosyncrasies, no quirks, and the visibility is outstanding. I go low and slow, so I can put on the autopilot and watch the sights go by during long cross-country trips.”

The Cruzer started flying with naked tiny tires (“I don’t like wheel pants,” Motley says), but then he had to power through the mud fest at the Flying M Ranch Fly-in and Campout in Reklaw, Texas. He attends almost every year, and it rained a lot in 2018, he said. “They used a tractor to haul out RVs with gummed-out wheel pants.” Motley replaced his 5-inch rims with 6-inchers and mounted medium-size tundra tires, an 8.00×6 on the nose and 8.00×21-6 on the mains. “That paid dividends at Oshkosh this year [2019]. We had just parked at Fond du Lac when we got the message that if you have tundra tires, come on in [to the rain-soggy field].”

A pilot since 1985, Motley supported his “passions and addictions,” as a part-time flight instructor. In 1995, “I snagged a Maule MX-7-160 for a rock-bottom price of $60,000,” he said, explaining that Maule periodically built a small block of hybrid airplanes as sales promotions. With a 160-hp Lycoming O-320 mounted to a four-seat M-6 fuselage and M-5 wings, “I flew it for nine years, from coast to coast, and put a little more than 900 hours on it.”

Starting his aviation life with model airplanes, Motley always wanted to build full scale, so after selling the Maule he went shopping at Oshkosh in 2007. Originally looking at RANS, he stumbled across the Sonex. He judged its construction techniques within his capabilities. And the airplane “was positive-G-rated for aerobatics and I thought, ‘Ohhh, that could be fun!’ ”

This was before Sonex kits were match-hole drilled, Motley said, and construction took three and a half years. “I was hoping that the power-to-weight ratio would be comparable to my Maule. It was 1200 pounds with 160 hp and the Sonex weighed 600 pounds with its 80 hp AeroVee engine. The mass was pretty close, but the wing planform was not.”

Standing a trim 5-foot-10, Motley discovered that the Sonex’s dual sticks would not do him any good at Denver’s density altitude, so he replaced them with a single stick. “I flew it as a big bubba single-place plane,” he said. “The performance was still marginal, but I got everywhere I wanted to go, often crossing the Continental Divide.” In 2014, he went to Key West with a stop at Sun ’n Fun.

After six years and 600 hours, Motley needed a roomier, more powerful airplane with backcountry capabilities. After being together quite a while, Motley married in 2015. “Natalia is taller than I am, and putting her in the Sonex was just too tight.”

Looking at buildable airplanes, the Maule guided his decision: high wing, side-by-side, lots of cargo space. After putting bigger tires on his Maule, he said, “I enjoyed camping and tooling around the backcountry strips in Idaho and Montana, and I was looking forward to getting back to that.” The Cruzer gives him all those capabilities along with great visibility, easy cockpit access and matched-hole, self-jigging construction. Motley discovered the Cruzer at Sun ’n Fun, stopping on his Sonex adventure to Key West. “I got Natalia to go with me to Oshkosh that year and had her sit in it. She said, ‘Oh! This is nice.’ That was my go-ahead, so I ordered the tail kit.”

Meeting the light-sport requirements was another deciding factor. It took Motley more than six months to overcome a nebulous lab value with a special-issuance medical certificate. “There’s no disease, no treatments, and my internist kept sending letters to the FAA explaining that I’m not sick. When I got the special issuance, I went Sport Pilot so I don’t have to mess with special issuance.”

Beyond LSA

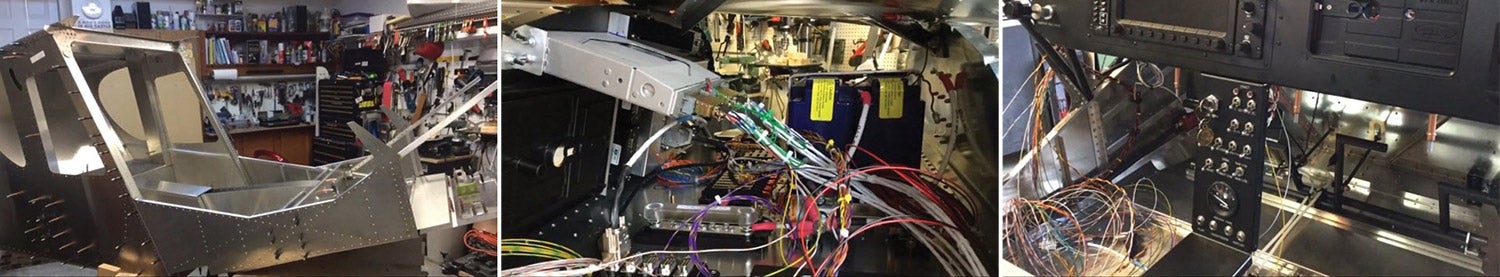

BasicMed freed him from Sport Pilot’s limitations and the need to build to LSA specs. “I have a fat Cruzer,” he said. “I loaded that puppy up with upholstery, carpeting, soundproofing, and some stringers on the fuselage panels to reduce oil canning. I put in dual coms and a full Dynon suite with 10-inch touchscreen display, an ILS/VOR system, dual-axis autopilot, Sirius XM radio and a couple of cup holders.” Dynon was upfront about its intercom integration with dual coms, Motley said. “It worked, but not as well as the PS Engineering audio panel. I put a HOTAS [hands-on throttle and stick] system so I can flip between the coms, disconnect the autopilot, transponder ident, control elevator trim and, of course, a PTT switch.”

With a primary wiring harness from SteinAir, Motley installed the avionics. Most of the boxes are remotely mounted, so he cut another access panel in the belly, just aft of the one under the baggage area, where the torque tubes connect the stick to the flaperons. “If I disconnect the control cables, I can stand up to work on the avionics, fuel pumps, filters, and other stuff. This also gave me a short cable run to the antennas,” he said.

“It’s amazing how much wire it takes.” In total, the avionics added 40 pounds. On the scale, Motley’s Cruzer registers 900 pounds when empty. Zenith publishes a max gross of 1440 pounds at 6 G’s. Working with the inspecting DAR, Motley derated the plane to increase its maximum gross weight. Dropping to 5.4 G’s gave him another 160 pounds without exceeding the published maximum structural limit. After a few years of aerobatics in his Sonex, he cannot think of an on-purpose situation that would get anywhere near 5 G’s.

Being a new kit, it took a while to get it; construction started in early 2016. He really wanted the wing kit next, but Zenith did the fuselage first, said Motley. “I like to build the tail, wings and then the fuselage because working in a two-car garage, it’s easier to put flat things out of the way. Once the fuselage is in place, you’re pretty much stuck.”

Zenith’s matched-hole kit really impressed Motley. “If you need a 2-inch piece of L angle, it’s already been cut and labeled. It’s not difficult to figure out.” The Cruzer made its first flight on September 30, 2017. “My wife and a friend who helped me with the long-arm stuff during construction were there, and it went well, with no significant issues,” he said.

“Stall speed depends on the weight. It’s in the mid-40s [mph] solo and high 50s with a passenger.” Like his Maule, he installed vortex generators on the Cruzer’s wings. His flight tests demonstrated some remarkable deck angles on power, up to 21°, he said. “It now has much better flaperon authority, and the real stall speed may have decreased about 2 mph. Now it just mushes during stall approach unless a vertical sheer comes along to stall the aircraft.”

Rebuilding the Phoenix

Motley said the tail graphic was, indeed, a stylized Phoenix, and it is flying over Colorado’s mountains. He found the graphics online and had a shop make them to the desired size. But why a Phoenix?

It’s a long story, he said, but the short answer is that he had to land in a field after his engine seized on a Phase I flight test. “The landing was great. But there was the barbwire fence I did not notice at altitude. Rolling into it and one of its posts crumpled the front gear leg, the cowl, and the prop and significantly damaged a strut.”

The engine at that point was the Viking, based on the liquid-cooled, direct-injected Honda Fit engine. Motley followed the Viking for a number of years through posts on Zenith sites. “There was no real negative stuff being reported on it,” he said, so when he had to make an engine decision, he essentially flipped a coin because the “engine costs about half the price of anything else we can do.”

After the initial installation, instead of starting, the Viking would blow its starter fuse. Viking said another builder was having the same problem, adding that it needed to update its wiring diagram. “The engine comes prewired with the ECU [engine control unit] and wiring harness,” said Motley. “You connect the positive and negative and run it through a fuse. So we redid the starter wire, put in a bigger fuse and still couldn’t get started unless I cranked it and cranked it. I called again, and the company said you’ll never get it started unless you inject starter fluid in the throttle body, and I got that in print.”

Motley finally got the Viking to run, but it would die when he reduced power. During an online session with the ECU’s vendor, it looked like it wasn’t producing enough fuel pressure. “My engine, the 130, is direct gas injection. It has its own mechanical pump mounted to the engine that goes from 40 to 2200 psi, and it is not constant delivery. It has a solenoid that has to be timed to the injectors.”

After Viking sent several ECUs with different programming and not getting reliable power, Motley removed the engine and returned it. When he got the engine back, it still would not start. Knowing that fuel pressure had a role in this drama, Motley installed a stock Honda fuel pump, and the engine started instantly. An air/fuel meter said it was running lean, but Viking said, “Don’t worry about it because you won’t be running at those settings.”

Motley started his Phase I testing with short flights of an hour or less. “About 10 hours in, I did a 2-hour flight in the pattern, and when I pulled the power back on final, the engine died. Coasting, it started sputtering as I flared; then it started and stopped again all the way back to the hangar.” Five Viking ECU updates later, flying out to the test area, “alarms go off, the temperature spikes, and the engine overheats.” Making an immediate 180° turn back to the airport, Motley says the engine lasted about 30 seconds before seizing. With a mixture of oil and coolant in the cylinders, “my theory is that it got so hot from being so lean that it separated the head gasket. The pressure in the cylinders blew all of my coolant overboard through the overflow bottle.”

Take Two

That was enough for Motley, and so he replaced the Viking with a 130-hp ULPower 350iS four-cylinder, air-cooled, FADEC-controlled engine. “I always liked ULPower. It’s kinda pricey, but it looks great, CNC’d in Belgium, with a lot of redundant features.” When there’s a problem, a warning light glows and the engine defaults seamlessly to a richer mixture. When the light went on, Motley noted that his fuel flow increased 0.6 gph. Two 14-gallon wing tanks, working through a 2-gallon header tank, feed the engine, which consumes about 6 gph in normal cruise flight.

After receiving a loaner, Motley sent his ECU to Belgium. “Sure enough they found a software bug,” he said, adding that ULPower said it was recalling about 10 other ECUs for updates. Installing the updated ECU just before AirVenture 2018, he’s had “no light, no problems” in the 250 hours he logged before heading to Oshkosh in 2019.

A two-blade, ground-adjustable Sensenich prop turns ULPower into thrust. Motley had a custom pitch pin ground to give him a finer pitch in Denver’s density altitude. (The Sensenich system uses a precision pin inserted into the hub that contacts lateral pins on the blade bases. The diameter of the pin determines how much pitch each blade has. The smaller the pin, the finer the pitch.) “It is such an easy system. I can land somewhere, repitch it, fly around the backcountry, repitch it again and leave,” he said.

Changing engines didn’t adversely affect the Cruzer’s center of gravity, but removing the heavier Viking engine left a large space between the engine and firewall. After checking his weight and balance calculations with several A&Ps, Motley built a small box in the space “for the 20 pounds of stuff you normally carry everywhere—oil, tie-downs, tools. That 20 pounds up front gives me about 50 pounds more in the back.”

Pain and Paint

Before running into the barbwire fence, Motley had planned on a professional paint job. Afterward, he just wanted to fly. When ULPower took him to Oshkosh in 2018, “I put big-ass Band- Aids all over where it was damaged and added a Humpty-Dumpty sticker.” Deciding he could better invest the cost of a pro paint job, he kept it simple.

During this adventure, Motley named his Cruzer Phoenix, and it’s been living up to its namesake. Another builder in the Cruzer community reported a crack in his horizontal tail’s leading edge. A month later, “after a long flight to Bryce Canyon, I found the same fracture pattern on the opposite end.” Communicating with Zenith and sending photos and a deconstruction video, the company re-engineered it, published a service bulletin and changed the kit. Later, when giving a friend a ride, on final approach the Dynon display “just started rebooting over and over again,” he said. “It got locked in that cycle. Then it displayed a splash screen that said if it continues, send it to Dynon. They did about $500 worth of warranty work on it.”

Since then, Motley said the Phoenix has been behaving. And he is eagerly looking forward to his backcountry camping trips.

In retrospect, we should have dug deeper into the reasons why Gary Motley’s Viking 130 failed in flight, resulting in damage but, thankfully, no injuries. Subsequent interviews with the parties haven’t shined a clear light on what caused it, though there is a lot of conjecture that, in our opinion, doesn’t serve a useful purpose. Suffice it to say, we did a disservice to Viking by not allowing the principals at the company to air their views when the article was published. We hope that providing this venue for rebuttal will help address the concerns people have raised regarding Viking engines due to our article. The company’s installed user base and positive anecdotal comments from customers should be considered part of the Viking story.