The press of business being what it is, I recently found myself in bucolically superior British Columbia at Murphy Aircraft. The major result of that trip will appear elsewhere in the forest at a later date, but for now I’d like to address an unexpected finding during my exotic international sojourn.

OK, so it wasn’t Beijing, but the speed limits are in kilometers, eh? And the breakfast buffets all have baked beans.

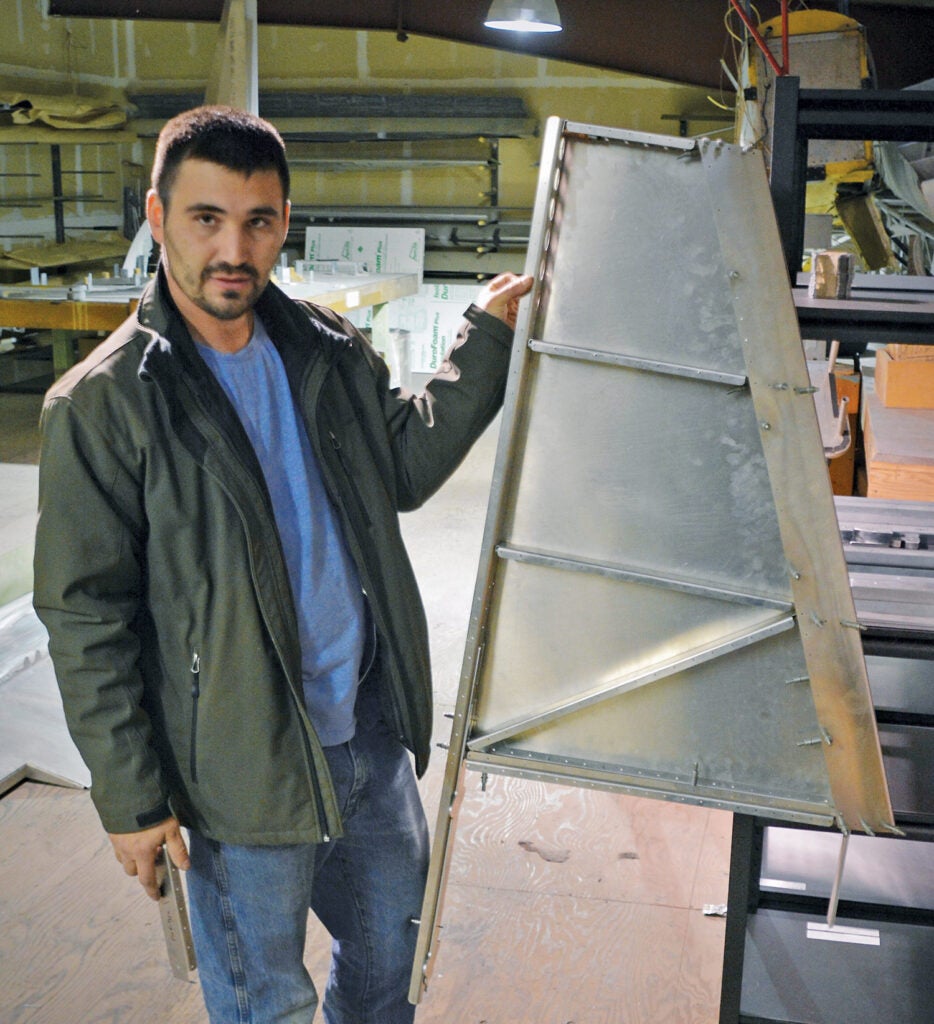

Taking the nickel tour around the sizable Murphy Aircraft digs, we came across a prototype vertical stabilizer kit that was nearly completely assembled. Other than one side panel and the whole being held together with Clecoes, the assembly looked ready to bolt on an aft fuselage. Yes, there was the matter of pulling all the rivets needed to actually stick things together, but the point was the stab just needed riveting. All the shaping, cutting, locating and predrilling was already done to the point where the stab could be permanently joined together. Doug Thorpe, of Murphy’s sales department, noted they were looking into shipping subassemblies in this remarkable state of finish.

“Hmm,” I thought silently. “Looks a bit too ready to go to me, but hey, that would sure speed things up.”

“Of course,” Doug continued, “we don’t have the 51% rule here in Canada, so this is fine for Canadian customers. In fact most Canadian customers have us assemble their airframes for them. But in the U.S. we’ll need to see if the FAA will approve it.”

Really. I didn’t know Transport Canada didn’t bother with the 51% requirement.

Well, the FAA does reconsider the 51% rule from time to time. You know, the requirement that the “major portion” (at least 51%) of the tasks needed to make the aircraft airworthy must be completed by amateurs “solely for their own education or recreation,” to poach from EAA’s website on the subject.

Back when an airplane “kit” consisted of drawings, two big sticks of spruce and a fiberglass nose bowl, there was little need to worry about who was building 51% of an airplane. Anyone willing to relive that much shop class was definitely getting an education at the very least. Or if they already knew how to do all those things, then they were definitely getting some recreation as well.

It was the advent of fast-build kits over 20 years ago that first got the FAA’s attention. To a legacy homebuilder nearly any kit today would seem a fast-build, what with so many pieces formed and drilled, and really, what is left is assembly, with precious little fabrication involved. But then we had the rise of fast-build kits where not only were the parts ready, they were also joined by the kit maker into major assemblies such as a wing or fuselage. Just enough was left undone to say the buyer had paid sufficient penance to qualify for 51% of the build. Fair enough. The FAA opines yea or nay after reviewing a kit and may mandate leaving a part or two undone to ensure the owner-builder is doing his share. But you know the kit passes muster when you buy it, and the FAA likely sleeps better figuring the kit is probably better screwed together anyway.

What really got the feds’ ailerons fluttering was when professional build shops became so unavoidably numerous and visible they could no longer ignore them. The rules said the owner had to build it, but maybe a pro shop does a better job than Joe Six-Pack trying a new hobby? That lead to another decision of how much outside labor an owner-builder could enlist on a project.

To further quote from a 2008 EAA article, “The FAA now defines 51% as the builder completing, at a minimum, 20% of the assembly and 20% of the fabrication with the remaining 11% made up from either additional assembly or fabrication. The FAA now states that the commercial assistance or ‘for hire’ building programs will not count toward 20% of the assembly by the individual.” All very good, as that gives us a pretty solid ruling on what homebuilding is from a regulatory standpoint.

But after taking a gander at Murphy’s stabilizer and realizing our northern neighbor finds no use for the 51% rule, plus further considering the utility and popularity of professional labor found in fast-build kits, or the pro results obtained by shops carefully outfitting such complex wonders as a Lancair Legacy or, my word, an Evolution, is it now time to ditch the 51% rule? Do we really need the 51% rule anymore? Or do we abandon the 51% requirement at our peril? Does it provide builders with some sort of protection from further FAA oversight, or is it time to enter a new era of general aviation where, practically speaking, who cares who builds little airplanes?

For sure times have changed. As Eric Tegler noted in an April 2021 article in Forbes, “According to Plane & Pilot magazine, the price of a new Cessna 172 was $12,500 in 1970 and the average salary in the United States was $6186. In 2021 dollars the 1970 sticker would equate to about $85,000.”

Today the approximate price of a new Cessna 172 is $450,000. I’m old enough to remember hanging around the local airport in 1970 and listening to what could be described as middle-class people chat about the new airplane they had just bought. No one was flying a 73-year-old airplane such as I do today when I wheel out my 1950 Cessna 140A. In 1970 there were no 73-year-old airplanes; Orville had flown only 67 years earlier. The Howard and Stearman antiques were maybe 35 years old then and normal people flew relatively new, factory-built airplanes.

Today, thanks to the multi-time faster-than-inflation rise in new airplane prices, the only reasonable path to new airplane ownership for mortals is homebuilding. As the certified airplanes fade from middle-class reality, Experimentals are the only alternative. But besides being more expensive, life is more demanding today and how many people have the time to even pop-rivet an LSA together? How long can the Cessnas and Pipers from the ’60s and ’70s glory days last?

Could a combination of kit manufacturers and pro-build shops, working unfettered by a 51% rule, provide significant downward pressure on new aircraft pricing? Would such a combination provide a large enough bump in customers to build some scale into the new-plane general aviation world? Would such a combination provide an incentive toward newer aircraft rather than resurrecting 50-year-old airframes as we’re doing now? How long before the 50-year-old airframes wear out?

Then there is the flip side. If the FAA were to rescind the 51% rule—just work with me for a moment—would that mean they would impose other restrictions on new builds? Would scratch building have to go away? Would only FAA/PMA parts be allowed? Would yet another category of aircraft need be developed by Oklahoma City?

Probably not because empirically we can see Experimentals as built today work well. But for sure pro shops would proliferate as time-harried customers look for a new airplane. And with the price of aircraft assembly so low, everyone from the kit manufacturers to guys in hangars could set up shop to assemble Experimentals for a profit.

For sure more specialty shops would come online. Just as pre-wired instrument panels and baffle kits are popular now, anything up to a complete build would be offered. Some planes would come together on speculation, and for sure wealthy pilots would keep many shops in business building custom turnkey airplanes to suit. But it wouldn’t mean enthusiast individuals couldn’t still build their own planes. And the FAA could retain the Experimental rules; they would simply continue to be anything not certified. Not that many certified airplanes would survive such competition.

Certainly I don’t expect anything to change soon, but again, how long before the pressures of busy amateurs looking for a modern airplane but facing an aging population of Wichita tin conspire to make streamlining the kit build experience a priority? In effect, could the old paradigm of a big certified factory turning out flying airplanes, now having morphed into today’s kit industry with its various methods of assisting or outsourcing assembly, further morph into kit makers selling to assembly centers that in turn sell turnkey airplanes to pilots? Given the low financial hurdles to entry, should the 51% rule disappear? Along with a shared liability path, could this be a way to upgrade our geriatric GA fleet? Would you mind taking possession of your next Experimental if the first time you saw it was when it flew into your local airport? It’s something to consider.

Great article, and great points. I know a big hurdle for me is the time to build.

need the cost of parts to come down too. $700 for LED replacement lights is extortion.

I’m somewhat concerned about unintended consequences. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought in the early days of aviation the US government recognized that flying would be important for the country and took measures to encourage design/build activities by private individuals. I thought the 51% rule was intended to insure that the builder was actually developing technical skill and more refined understanding of all matters aeronautical. The result would be safer airmen as well as a reservoir of talent which the government could draw upon, if necessary.

It often seems to me that this enlightened attitude toward GA has been substantially weakened, and that perhaps there are strong elements that would prefer that GA just go away.

If individuals don’t build, the variety and customization that we are currently free to enjoy will disappear. We’ll see the MBAs lobby for professional building only (with a “safety” justification), and eventually we’ll be limited to only approved designs, from a few vendors.

If the 51% requirement is dropped, we’ll almost certainly stop producing such tech-savvy pilots. And once home-building becomes rare, it seems possible that it would even be outlawed. Use it or lose it!

I’d be interested to see what others think.

LR

I know a guy that has purchased a mid 90’s Saratoga wrecked with no engine or avionics and is building a set of new wings (less spars, and gear) from scratch, replacing most of the skins, fabricating and installing all new glass, and hanging some sort of turbine on the front. All new experimental avionics / panel auto pilot. He has worked with the FISDO and this will equate to more than 51%. Of Course it will no longer officially be a “Saratoga”. He is applying corrosion protection very carefully and will likely end up with a superior aircraft when completed. From that prospective, one could get a hold of a set of helio courier bluprints and build it from scratch. This provides another view of the 51%, and is certainly doable.

BT