As a young Air Force communications officer at Kincheloe Air Force Base, Michigan, in 1962, 1st Lt. Richard E. VanGrunsven yearned to own a sporty, aerobatic, affordable airplane to fly in his off-duty hours. “At the time, there was nothing to buy that did what I wanted it to do…fast and aerobatic, single-seat and sporty,” VanGrunsven recalled.

As a young Air Force communications officer at Kincheloe Air Force Base, Michigan, in 1962, 1st Lt. Richard E. VanGrunsven yearned to own a sporty, aerobatic, affordable airplane to fly in his off-duty hours. “At the time, there was nothing to buy that did what I wanted it to do…fast and aerobatic, single-seat and sporty,” VanGrunsven recalled.

He knew he couldn’t find a factory plane that would fulfill those desires. The only model that came close was the Stits SA-3A Playboy, a low-wing, homebuilt aircraft featuring a fabric-covered, welded steel-tube fuselage and tail and strut-braced fabric-wrapped wood wings. VanGrunsven bought his first Playboy in May 1962 from a pilot in St. Louis. But after only a few months, he soured on that plane, mainly because he felt it was underpowered.

Later that summer, he found a second Playboy near Chicago—but it lacked an engine and needed some repairs. His first cross-country trip with this plane was on a trailer, wings off, back to his base. Van, as he would later come to be known, was certain that with the modifications he had in mind, this Playboy could be a far better airplane.

Over the next year, Van continued flying his first Playboy while making incremental major and minor improvements to his second plane, to include installing a 125-hp Lycoming O-290-G ground power unit engine and adding new wingtips, a fiberglass engine cowl and bubble canopy.

He was pleased with the enhanced performance provided primarily by the beefed-up power, nearly double that of the 65-hp Continental engine that designer Ray Stits originally had intended for the Playboy. Van flew the plane extensively in his off-duty hours while selling the first Playboy along the way. He took his new aircraft back to Oregon when he finished his Air Force service in the fall of 1964.

Over the next three years, Van continued to make improvements to the plane, designing and installing aluminum cantilever wings with landing flaps, a more aerodynamic engine cowling, new, lighter landing gear and larger tail surfaces. At the time, he wrote that the sum of these modifications contributed to improvements in his ship’s “total performance,” a phrase that would live on for the next five decades and beyond.

The RV-1

He re-registered his Playboy with the FAA as the VanGrunsven RV-1, listing himself as the manufacturer. He flew it for the next three years, including three cross-country trips to the EAA convention, then held in Rockford, Illinois, a show that was the precursor to AirVenture in Oshkosh. The RV-1, Van said, received a “moderate amount of attention.” He sold the RV-1 in 1968 to a Texas airline pilot who showed more than a little interest in the plane and made Van an attractive offer for it.

He established Van’s Aircraft on March 16, 1970, in the hope and belief that the hundreds of Playboy owners at the time also would want to dramatically improve their planes in the same ways that he had. He advertised plans and parts for his upgrades, including wing and aileron ribs, fiberglass wingtips, engine cowls and wheel fairings. He sold a few dozen sets of these plans for $25 each, but as far as he came to know, only one other Playboy owner ever used them to modify his aircraft.

Disappointment in his RV-1 plans and parts sales spurred Van to design the RV-3, which he believed could be a better version of the RV-1 to fill a perceived market void. He put aside his work on the RV-2—an all-wood sailplane that he never finished—and began building his prototype RV-3 in a 16×24-foot workshop that he created on the second floor of a barn on his family farm. This would be a so-called “clean sheet” all-metal design modeled largely on the RV-1.

He did not anticipate that his almost three years of work would yield the airplane that would put Van’s Aircraft on the map and, over the next five decades, kick off a revolution not only in the homebuilt aircraft industry, but also in general aviation in the United States.

The Three Takes Off

The RV-3 was an almost instant hit when Van debuted the prototype in 1972 at the annual EAA airshow, where it won the award for Best Aerodynamic Features. The plane received the first of what would be many glowing reviews in EAA’s Sport Aviation magazine with the headline “The Amazing RV-3.” Word spread quickly, with Van attributing the buzz to “the overall sex appeal of the airplane. It was fast and it was aerobatic and it looked like a hot rod,” he said.

Sales of RV-3 kits soon took off well beyond Van’s expectations, and for the first time he believed that he could make a living solely through his growing business. At that point, he had no plans to design or build any other models, but prospective customers soon began to ask about a two-seater. Van was hesitant, believing that some performance would have to be sacrificed, but he moved ahead in designing the RV-4. He was surprised by its performance—much closer to the RV-3’s characteristics than he thought possible—and demand for this tandem-seat plane skyrocketed immediately after its 1979 debut, with sales eventually outpacing its predecessor.

Moving Seats

Soon enough, potential buyers began inquiring about a side-by-side version, which led to the introduction of the RV-6 in 1986. More than 300 empennage kits for that model were ordered in the first year alone, and the plane became, and has remained, the best-selling RV.

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the kit-aircraft industry benefited from a precipitous decline in production and sales for single-engine certified aircraft, driven by high prices and a saturated market, among other factors. Conversely, affordability and greater support from the Federal Aviation Administration drove demand for, and acceptance of, kit airplanes—and Van’s kits were no exception.

As demand for his three RV models grew, the customer demographic broadened, and Van knew that making the kits easier to build was imperative. Through the 1990s, builders of the RV-3, RV-4 and RV-6 generally hewed toward craftsmen and the mechanically inclined, and the Van’s kits were mostly a collection of raw materials that required 3000 to 4000 hours of work to create an airplane. While the Van’s kits were affordable, the company recognized that many prospective owners were not entirely confident in their abilities to build an airplane, according to Andy Hanna, Van’s chief engineer from 1991 to 2000.

“It was the difficulty, not the dollars,” Hanna said. “The approach then was as if every (builder) was an engineer who probably had some airplane building experience. We thought we needed to develop plans and a manual that took more of a step-by-step approach, a more ‘hand-holding’ approach.”

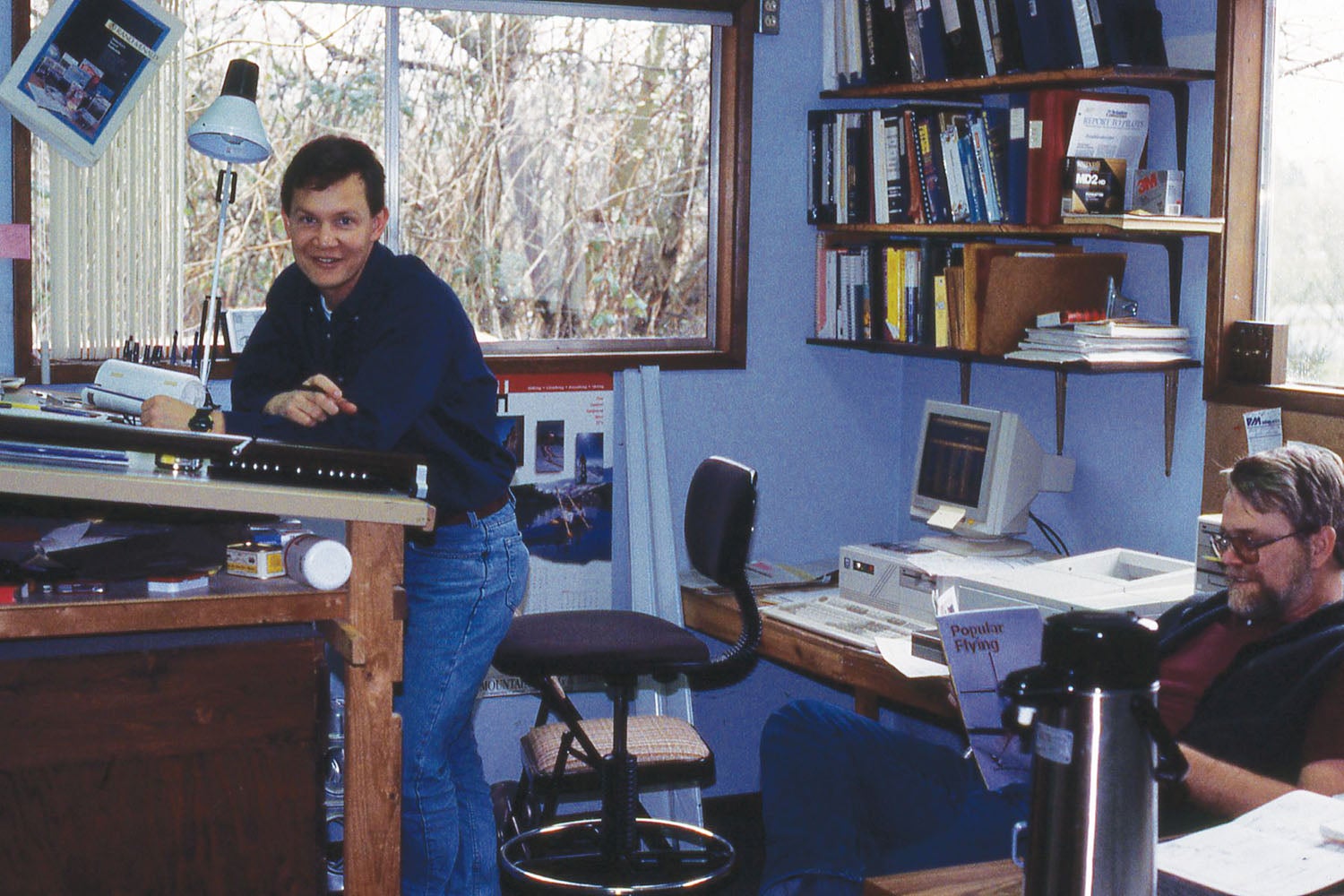

Beginning with the RV-8, Hanna led the way in what could be considered revolutionary changes in kit production at Van’s. The engineering department moved into the modern era, shifting away from hand-drawn, two-dimensional scaled drawings to using CAD software to design the planes and parts. At about the same time, Van’s acquired its first press for forming and punching aluminum parts. The computer programs led to more precise isometric drawings and user-friendly plans, and the parts that emerged from the new press relieved builders of much of the tedium of measuring, cutting and forming complex shapes and drilling hundreds of holes in skins and other parts.

“We probably cut the building time in half,” Hanna said. “I also think that it lessened mistakes, lessened frustration, made building a more pleasant process and, hopefully, got more people flying. The path to selling more airplanes and having happier builders was to simplify the process. We were helping the builder get to a finished airplane.” In the ensuing years, the engineering and prototype teams focused on further refining the kit parts and components. They created clearer, more concise plans that incorporated a page-by-page, step-by-step process and included in the kits almost everything required to assemble an airplane from spinner to tail.

The so-called “matched hole” formula devised by Van’s engineers allowed them to produce skins and understructures, particularly around complex curves, with rivet holes that aligned perfectly and made the structure self-jigging. The need for homemade fixtures was greatly reduced. The RV-8 was the first kit designed with this new technique, and it marked an important shift at Van’s. “I would say that was the beginning of the modern era of Van’s…what really started to help sell airplanes,” said Rian Johnson, president of Van’s, who was on the engineering team under Hanna at the time. “It was really the thing that gave us the edge over everybody.”

Johnson, who began his career at Van’s in 1999 immediately after graduating from the University of Portland, believes that the next transformative improvement to the builder experience was a modification of the kit plans. Prior to the RV-10, the plans consisted of scaled two-dimensional drawings on 24×36-inch sheets and a builder’s manual written in a narrative style. The engineering and prototype teams came up with a way to incorporate clear, concise step-by-step instructions onto 11×17-inch drawings, most of which were isometric images of parts, structures and components.

This change simplified the building process while also giving builders greater confidence in their ability to handle a Van’s kit. “If you follow the steps, everything is there,” Johnson said. “Those (new) plans took people from, ‘I don’t think this is possible,’ to ‘OK, I can do this.’”

“I think we’ve learned that there is a big market for an airplane kit that is developed to the point at which when you open the box, you could shut the shop door and build the airplane,” said Scott McDaniels, who has worked in the Van’s prototype shop since 1996. “For the most part, everything is there, everything’s been thought out. And if you build it the way that we tell you to build it, you’ll have a safe, dependable airplane.”

Around the same time, Van’s also developed firewall-forward and wiring packages, other areas that had challenged many builders. Johnson believes the net effect of these improvements was to help builders build safer airplanes. “We were increasing safety by making the kits more buildable,” he said.

Perhaps topping the list of things builders can purchase to shorten the time to completion is the kits’ so-called “quickbuild” option, which includes mostly completed fuselage and wings and came on the scene beginning with the RV-6 in 1996. Van’s estimates that this option allows building time to be cut by up to 40%—a reduction of 1000-plus hours.

Ken Scott, who worked in a variety of roles at Van’s from 1989 to 2016, including a stint as a technical advisor to the builders, believes that the quickbuild option significantly increased sales as soon as it was introduced. “It showed us that there was an almost endless demand for ways to make building faster,” Scott said. “People were willing to spend money on things that made it quicker.”

Today, the company has contracts with companies in the Philippines and Brazil to build fuselages and wings for the RV-6, RV-7, RV-8, RV-9, RV-10 and RV-14. In its ongoing efforts over the years to keep costs down and quality up, Van’s has increased its in-factory parts production.

Suppliers as Partners

But a big factor in the company’s success also can be attributed to the component suppliers it has used over the past 50 years. Van’s has relied on a network of suppliers for specialty kit components, from fiberglass cowls, wingtips and wheel fairings, engine mounts and other welded parts to plexiglass canopies, landing gear and exhaust systems. “Our suppliers are a critical part of the Van’s community,” said Greg Hughes, Van’s vice president and chief operating officer. “Van’s Aircraft never would have become what we are today if it wasn’t for our business partners.”

Harmon Lange, of Langair Machining in Warren, Oregon, has machined more than 30,000 landing gear legs for every RV model since 1969, first from his machine shop in Wausau, Wisconsin, and since 1995 in his shop about 50 miles north of the Van’s factory in Aurora, Oregon. A builder of six homebuilts, including an RV-4, RV-6A, RV-8A, RV-9A and RV-12, Lange shares Van’s philosophy of “simple is best,” and the Wittman-style landing gear legs that he makes for the majority of the Van’s lineup reflect that. “The secret to the Wittman gear is simplicity—a tapered rod that just bolts to the aircraft,” Lange said of the 6150 steel legs created by aircraft designer Steve Wittman. “They have the right balance of strength, weight and impact absorption that make them an ideal fit for the RV aircraft.”

As with any other profession, interest and hobby, RV pilots and builders around the world share an affinity for Van’s airplanes, and have myriad ways of finding and connecting with each other. They convene at gatherings such as EAA’s annual AirVenture and regional fly-ins around the country, meet through builder’s groups and, increasingly, link up online.

By far, the most popular destination in cyberspace is vansairforce.net. Site administrator Doug Reeves said the website has more than 32,000 registered users, but he believes that it receives upward of 150,000 regular visitors. The site grew in the late 1990s from a small online page called “The RV White Pages,” essentially an online phone directory that Reeves created for RV builders in North Texas who wanted to connect and help each other.

“I thought it would be neat to meet builders in my area, but it just continued to grow,” said Reeves, who built and flies an RV-6. “I couldn’t stop it.”

The job of maintaining the growing site led Reeves to leave his IT job to focus on it full-time from his North Dallas home. Today, the site provides forums for users to buy, sell and trade airplanes, kits or parts, seek technical advice, share flying experiences and photos, promote RV-related events, swap stories and more, all for free—although he politely encourages users to make an annual $25 donation.

The site features advertisements geared toward RV owners, and Reeves said it has gone well beyond his original intent. “I started it with the goal of focusing on RVs, but it morphed into something more aligned with being about the people who build and fly RVs than about the actual planes,” he said.

David Howe of Lemoore, California, who has built an RV-4 and a Harmon Rocket II and is now building an RV-3B, uses the site for getting and giving advice on all things RV. Howe says he logs onto the site every day to learn something new or share what he knows.

“There is a tremendous benefit, especially to the owners who did not build their RVs. It is a true lifesaver for those folks out there who have little or no experience in the maintenance or operation of these aircraft.”

Another longtime Van’s partner is certified flight instructor Mike Seager. Since 1993, in a special business arrangement with Van’s, Seager has been teaching people from newly minted pilots to career airline captains to fly RVs from a 3000-foot grass strip in rural Vernonia, Oregon, about 45 miles north of Portland. He’s lost precise count, but estimates that he has trained some 7000 pilots from all over the world, logging more than 20,000 flight hours in RVs in the process, giving him a unique perspective on the planes and the people who fly them. Beginning with his first ride in 1982 in the back seat of an RV-4 piloted by Van himself, Seager has been convinced of the virtues of the Van’s designs.

“There’s no airplane out there that has the performance of these airplanes,” said Seager, who has flown every RV model and has built two RV-6s and an RV-4. “I don’t mean just top speed—it’s the combination of outstanding takeoff performance and climb speeds, slow landing speeds and short landing distances and fuel economy. They basically do everything well. They just are delightfully light to fly.”

But 50 years after Van introduced the RV-3—the model that he still staunchly believes is far and away the best performer of all—and with just over 11,000 RVs currently flying and hundreds more under construction, those who have known and worked for Van over the years insist that the success of the company began with, and continues to be led by, his prudent approach to business, as well as his honesty and integrity. Hughes believes that in the modern era of Van’s, the company’s success continues to represent Dick VanGrunsven’s original desire and vision to create good, all-around kits that result in fun and nimble airplanes.

The phrase “total performance” that Van used to market his RV-1 plans and parts is still featured in the company’s marketing materials and remains a guiding credo at the company. “Total performance is a fancy term for finding the best balance of all the really good things that make an airplane great and fun to fly,” Hughes said. “It needs to be fun to fly. It needs to handle well. It needs to be safe. It needs to be able to combine and balance all of those things. That’s what makes an RV an RV.”

Photos: Courtesy Van’s Aircraft.

Nice article, Dave!