Welcome to our annual Engine Buyer’s Guide, where we try to dissect what’s new, what’s old and what’s changed in the world of Experimental-intended powerplants. Last year we reported the supply chain issues vexing aviation engines were slowing down. We were partially right. The majority of engines and parts are more readily available now, but stubbornly many remain elusive, especially for the big mainstream manufacturers. In fact, some parts are more difficult to come by and, if anything, obtaining new engines from major manufacturers, notably Lycoming, arguably took longer in 2024 than in 2023.

Welcome to our annual Engine Buyer’s Guide, where we try to dissect what’s new, what’s old and what’s changed in the world of Experimental-intended powerplants. Last year we reported the supply chain issues vexing aviation engines were slowing down. We were partially right. The majority of engines and parts are more readily available now, but stubbornly many remain elusive, especially for the big mainstream manufacturers. In fact, some parts are more difficult to come by and, if anything, obtaining new engines from major manufacturers, notably Lycoming, arguably took longer in 2024 than in 2023.

To be blunt, some shops say orders with Lycoming placed in mid-2024 might not be filled until very late 2026! Lycoming says more like a long year.(Last we checked, a year was 12 months.) Continental says nine months; independent rebuild shops hover around eight months. Patience and ordering well ahead are required (more than a year in advance), but new engines and parts are being built. Some engine suppliers, notably Rotax, which currently has a 30-day lead time, and the niche specialists repurposing auto engines have far quicker delivery dates, possibly as short as two months. Checking in with your supplier in advance remains excellent advice.

Those Prices

Unfortunately, we must also report costs rose shockingly starting two years ago and are still rising today, though often at a thankfully much slower rate and in several cases not at all. Inflation has definitely taken its toll, continuing supply issues don’t help, demand—at least so far—has remained strong and aircraft engine prices, silly expensive to begin with, have risen to absurd levels. The time-honored cost-saving tactic of rebuilding good core (used) engines is more viable than ever, but that option is under cost pressure too. This is due to the tight supply of new engine parts such as cylinders, plus the pool of rebuildable core engines and parts is thinning. Still, a rebuilt engine from one of the major rebuild houses is the prime alternative to the stratospheric price of new engines. That, and considering some of the alternative engines offered by smaller engine makers.

The final word on pricing, however, is this: Powering your airplane is not the place to cut corners. From both safety and performance standpoints a quality powerplant pays for itself. Obviously reliability is crucial to safety, but it’s also important to match the engine to your airframe’s needs and provide you with the performance to make your overall investment worthwhile. Even though engines are a major cost, it’s smart to make all the investment necessary to arrive at the plane you want.

About This Guide

Engines in the 160- to 200-hp range dominate new Experimental builds. Add in more specialized aircraft on either side of that core market and engines between 100 and 400 hp account for nearly all Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft coming together today, so that’s what we’ll highlight in this guide.

We also cover the odd turbojet, turboprop, radial, rotary, Wankel, electric or what have you when they’re primed for Experimentals. The idea is to give a broad overview of the market along with enough specific information to help you narrow down your engine search.

Providing that broad outlook means we list current engines in the main text and put not-for-sale engines of interest in the “Circling the Airport” sidebar. This catch-all includes engines just emerging onto the market along with old stalwarts barely in or long out of production but included because many remain in service, parts are available and you might run across them in your engine search. As always, this is a guide, not a catalog, so use it as a point of departure in your research.

Selecting an Engine

It sounds basic, but the first thing to know when engine shopping is yourself. Are you a practical sort building your first plane for transportation and general entertainment flying? If so, stick to tried-and-true engines from popular companies. They offer the most well-sorted, best-supported power options, which is what you need.

If you’re building a second or third airplane, or have a strong engineering background and are interested in something different and don’t mind the hiccups of off-Broadway engines, then go ahead and branch out if you want. Remember that specialty players require more hands-on involvement making brackets and such. This is fine for the experienced builder but it’s overwhelming for a newbie.

Generally speaking, go with the airframe kitmaker’s engine recommendation. These may include an auto conversion or small-volume engine maker, and that’s fine if they offer a firewall-forward kit or tech support knowledgeable with your airframe. Every time you depart from the plans adds time and uncertainty. Maybe even risk.

Those Clones

Lycoming engines might or might not be built by Lycoming, since the great “clone craze” of the early 2000s brought physically similar if not identical engines to market. Collectively these non-Lycoming “Lycomings” are casually referred to as clones, but each has its own upgrades and special features while remaining mainly interchangeable with Lycomings. They certainly are drop-in replacement engines with identical Dynafocal mounts and use standard cooling air baffles and so on. Continental sells their clone under the Titan brand name; Superior labeled theirs as XP. The Superior XP line has not been offered as a complete engine—parts are still being sold—for several years now, but you may come across these engines on the used market.

Auto Conversions

Converting automobile engines for aviation use is gaining popularity, mainly because auto engines keep getting better. Once very iffy foundations for an airplane engine, some of today’s auto engines can serve in light aircraft if properly prepared and supported. Luckily, well-sorted auto engines and installation packages from AeroMomentum, Fly Corvair, Viking and others are available. You’ll benefit from the engineering put into the conversion package (for a penny on the dollar, we assure you), plus you can (and should) talk with earlier customers with real-world experience with the engine package. Also, stick close to auto conversions that retain stock core engines. Enthusiasts often want to hot-rod auto engines for aircraft use, but that’s bad policy. Stick to the proven stock engine configuration and leave hot-rodding to racers who are used to dead-stick landings with oil on the windshield. While auto-to-airplane engines can work, it’s an immensely complex subject with absolutely no mercy for the neophyte trying to develop his own auto engine package.

Used, Overhauls, Rebuilds and Remanufactured

You don’t have to buy new. Remanufactured, rebuilt and overhauled engines have specific meanings when talking about certified engines. Remanufactured means an engine reset to factory-new specifications by the original engine manufacturer or one of their affiliate shops. Rebuilds involve a used engine rebuilt to new or close-to-new tolerances; the term is commonly used in casual conversation to mean any engine run through an engine shop.

Overhauled is yet another legal definition in the certified world. It’s a used engine brought to within the minimum service limits defined by the manufacturer. In other words, an overhauled certified engine could be rather near to worn out after “rebuilding” and hopefully priced accordingly. In practice, a rebuilt engine has many new parts in it. Typically the original crankcase and steel parts such as the crankshaft, connecting rods and often the timing gears are serviced and reused. Many minor parts are also reused. But the highly stressed cylinders and associated parts are normally brand-new. If you simply stick new cylinder assemblies on a used crankcase (typically without removing the crankcase from the airframe), that’s called a top overhaul. A tech might say such an engine was “topped.”

Rebuilding and topping Lycoming and Continental/Titan engines is absolutely par for the course. Rotax engines are also gaining popularity as rebuilds. Auto conversion engines are usually cheaper to simply replace with a new engine. Given the unregulated state of automotive engine rebuilding and the automated, close-tolerance methods of modern auto-engine production, it’s the smart way to go, too.

Where To Buy Airplane Engines

Many kit companies offer engines to their customers—tick the box when you order the kit—but you can also order directly from an engine manufacturer or one of their dealers. Be aware engine makers don’t keep engines in stock. There are too many engine variations and too few sales to keep anything in stock, so your engine will be built to order. And here you have the choice of a bone-stock engine as you might find on a Piper or a noncertified, custom engine. Lycoming’s Thunderbolt division provides the custom engines under that brand, while Titan is the name for Continental’s version of custom engines. At the other extreme, Rotax is right at home in both the certified and Experimental markets and has no need for an in-house boutique or separately named engines. A Rotax is a Rotax. Well, at least until it is modified by Edge Performance and becomes an Edge engine, but that’s an entirely separate company. Rotaxes are sold via several distributors in North America; see the Rotax heading below. A final note: Continental no longer sells engines directly; all sales are through Air Power Inc.

Non-Factory Sources

Once past factory-new engines we enter the realm of rebuild shops. The purchasing process becomes less formal and more customized because options are what rebuild shops excel at. Rebuild shops range from large businesses with over 30 employees that offer a warranty to small man-in-a-hangar operations. Some of the larger shops are well-known such as, but not limited to, Aero Sport Power, Barrett Precision Engines, Ly-Con Aircraft Engines and Pinnacle Aircraft Engines. All of these shops overhaul certified engines as their bread and butter but also specialize in Experimental, sport, backcountry, racing, aerobatic and other performance powerplants. Some make their own line of special parts and have hot-rod knowledge even the factories likely don’t possess, plus they offer services such as dynamometer break-in or small parts manufacturing. If you’re looking for something special, racy or show-worthy these are where to go.

These rebuild shops are cost competitive, too. If you have a core four-cylinder Lycoming somewhere, $40,000 should get it overhauled at one of these shops. If you don’t have a core…then yes, a rebuildable core might cost an additional $20,000. That’s still better than a factory-new Lycoming and from a performance and resale perspective an overhaul from a reputable shop is as good as factory new.

Size and longevity are good signs in an engine shop, but smaller shops can do good work, too. It’s worth noting the truly small operations don’t have machining capabilities and must work with specialist firms or one of the big engine shops for things such as connecting rod reconditioning, balancing, crankshaft or lifter grinding, engine case machine work and many other functions—which is fine. What these small shops really do is provide a valuable service sorting through all the possibilities with you, providing a local parts source and final assembly of an engine using parts machined elsewhere. Where these small shops source their machine work and what volume of work they do give a clue as to their viability. Finally, they might be a little faster to deliver an engine than the bigger shops depending on workload.

That’s the big picture. Let’s get into the engines available today.

Flat Four-Stroke Gasoline

AC-Aero/Aircraft Service & Parts Corporation

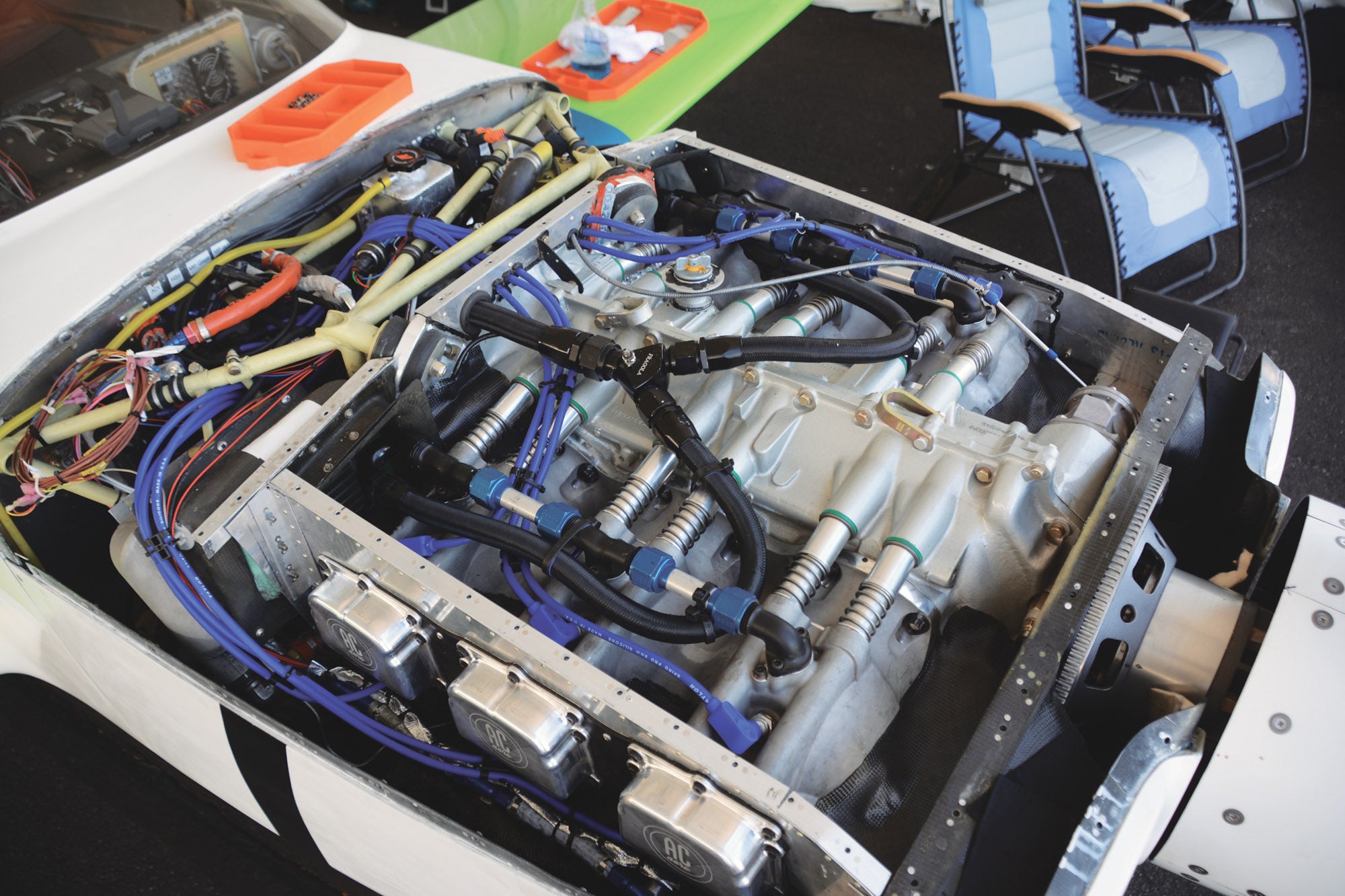

Converting air-cooled 320/360/390/540 Lycomings into big-inch liquid-cooled engines is AC-Aero’s game. The liquid-cooled cylinder assemblies and crankshaft stroker kits were designed by Andy Higgs and are cast and machined in Japan. All installation and engine building are done in Bakersfield, California, by Aircraft Service & Parts. A couple squadrons worth of engines have been built, says ASAP, and demand continues from the well-heeled clientele who can support these top-end engines.

In the AC-Aero and ASAP argot Legion refers to the stroker kits. The four-cylinder liquid-cooled cylinders are Gladiators; the six-cylinder liquid-cooled cylinders are Centurions.

ASAP keeps a large supply of AC-Aero parts in Bakersfield as they’ve found a subset of their engine build customers are eager for the greater power possible from the larger displacement. With parts on hand, the typical lead time from ordering an engine to delivery is three months. AC-Aero’s most accessible offerings are four- and six-cylinder stroker kits offering 409 inches for four-cylinders and 613 cubes for six-cylinder Lycomings. ASAP also offers the stroker kits with standard Lycoming angle valve cylinders used in the 390 and 580 engines. That gives 440 and 660 cubic inches, respectively, along with better breathing, much more power and measurably more weight than parallel-valve engines.

More involved are the four- and six-banger liquid-cooled cylinder packages. These are completely new two- and three-cylinder bank castings, configured to run on standard Lycoming bottom ends. They turn a Lycoming into a liquid-cooled engine, in other words. Advantages of the liquid-cooled cylinder banks are an advanced combustion chamber, improved tolerance for lower octane unleaded fuel, tighter piston and piston ring tolerances and elimination of shock cooling, along with a little less weight compared to air cooling before adding the radiator and plumbing.

The liquid-cooled cylinders are also big-bore units using Lycoming’s 390/580 bore diameter and are usually combined with the stroker kits to answer the “ain’t no replacement for displacement” call. Thus, liquid-cooled and stroked engines also measure 440 and 660 cubic inches for the four- and six-cylinder engines respectively. Nothing like having 110 cubic inches per cylinder to wow ’em at the pancake breakfast—or pylon race.

All AC-Aero engines are noncertified designs aimed at maximum performance and efficiency. They are not inexpensive, and the liquid-cooled versions require integration to the airframe to accommodate the radiator. Still, they offer features unavailable elsewhere.

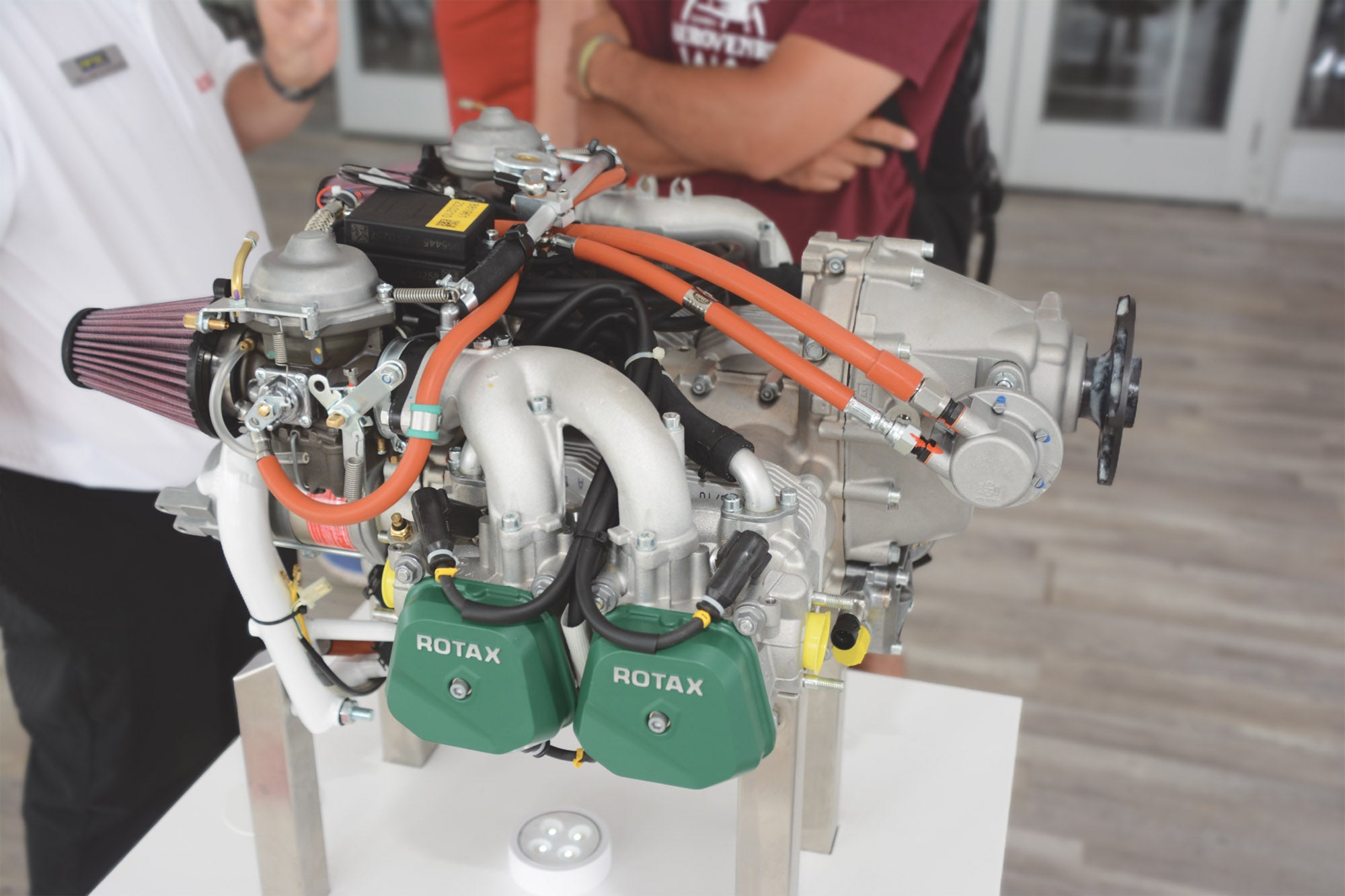

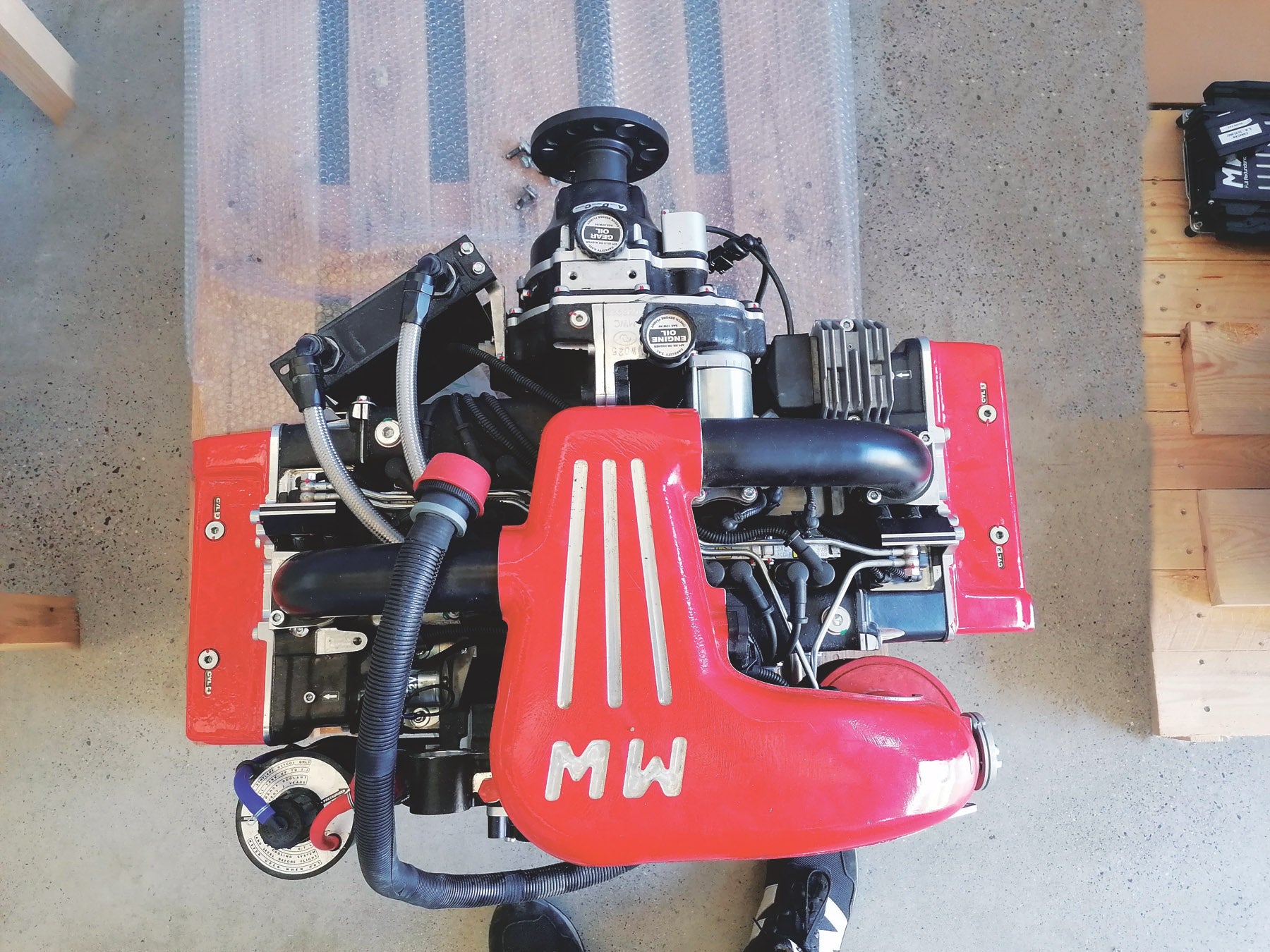

BRP Rotax

A division of Bombardier, Rotax builds engines for the greater BRP empire including side-by-side utilities, boats, personal watercraft, snowmobiles, motorcycles and light aircraft. Rotax is thus a larger engine maker than it may seem at first, with world-class production facilities and engineering, likely the best in piston aviation.

In the United States, Rotax sales are currently represented by Lockwood Aviation Supply in Sebring, Florida; Motive Aero, servicing the Western U.S. from their base in Hurricane, Utah; and Leading Edge Air Foils in Lyon, Wisconsin.

There are no changes in the Rotax lineup for 2025, so the big news remains the release two years ago of the 916 iS turbo four-cylinder. With 160 hp for 5 minutes and 137 hp continuous up to 23,000 feet, the 916 iS is Rotax’s current top-of-the-line engine and a real shot in the arm for STOL aircraft such as the Carbon Cub UL and the Kitfox Super Sport, among others. Its extra power, especially at high density altitudes, justifies its high cost and it’s sure to find its way into speed-oriented airframes thanks to its excellent power-to-weight ratio.

The Rotax’s small displacement—just 83 cubic inches—and high 5800 rpm redline make a compelling power-density argument. Those 83 cubes constituting an entire 916 iS engine are less than the 90 cubic inches of a single Lycoming 360/540 cylinder. Given the same 1.9 hp per cubic inch efficiency, a turbo’d 540 would be making 1040 hp. That’s more than the hottest Sport class air racers, yet the Rotax has a 2000-hour TBO, runs on mogas and doesn’t need anti-detonant injection (ADI).

Like all four-stroke Rotax engines, the 916 uses air-cooled cylinders and liquid-cooled cylinder heads. Oiling is via dry sump with a remote oil tank. Electronic fuel injection and ignition are standard; 12- or 24-volt electrics are available. Furthermore, the 916 can support hydraulically controlled constant-speed propellers. Speaking of which, the gearbox (PSRU) is now either a Version 2 strictly for fixed-pitch props or Version 3 for constant-speeds and fixed-pitched with minimal adaptation.

The only downside to the 916 is cost at $54,000 in round numbers. If you can live with 19 less peak, just 2 less continuous horsepower and a 1200- versus 2000-hour TBO, the 915 iS, upon which the 916 is based, costs $10,000 less.

Still the bestselling Rotax is the time-tested carbureted 912 series, available in 80-hp form as the 912 UL or with 100 hp as the 912 ULS. Like all Rotax engines, these do best on unleaded mogas because the lead in 100LL eventually fouls plugs and accumulates as sludge in the gearbox.

Besides the new 916 iS, Rotax offers two other turbocharged engines: the 115-hp, carbureted 914 and the just-mentioned fuel-injected 915 iS at 141 max continuous horsepower, now in its seventh year of production. All of these engines are built off the original 912 architecture (upsized for the 915 and later), so are horizontally opposed, water- and air-cooled, with spur gear propeller speed reduction units and hydraulic valve lifters.

A trend worth mentioning is that the lower-power Rotax engines are now being rebuilt thanks to sufficient core engines and good parts availability (some with reduced prices in 2024). This saves a little money over a new Rotax, but when every dollar counts it’s an option.

Continental Aerospace Technologies

Continental offers a surprisingly large number of engines ranging from legacy units such as the O-200 to a stable full of Jet A-burning piston designs obtained from German/Austrian programs. Probably the most popular are Continental’s big-bore IO-550 and its turbocharged TSIO-550 stablemate found in various Lancairs and a host of certified aircraft. Excepting the O-200, all of these engines are now too expensive new from Continental as certified engines (typically well over $100,000 and sometimes double that for diesels). More realistically for Experimentals, the 550s are appropriated from salvage yards or rebuilt by custom engine shops, so we have not listed these engines in the specification charts.

But Continental is very much in the Experimental market, with products under the Titan name. When Continental’s parent company purchased Engine Components Inc., it got ECI’s intellectual property and manufacturing ability to craft Lycoming clone engines. It has further developed these engines as Titans, thus replicating Lycoming’s parallel-valve engine architecture but with numerous upgrades. Titans are currently offered in 340 and 370 cubic inch displacements with power ratings ranging from 174 to 195 hp. Sadly, the Titan version of the six-cylinder 540 is not currently in production.

Titans come stock with some unique upgrades. For example, Titan sumps/intake manifolds are a magnesium version of the traditional “hot sump” casting, saving a meaningful 7 pounds. Optional sumps are either Titan’s vertical or Superior Air Parts’ cold air intake with a forward-facing throttle body inlet. There is no forward-facing hot sump or rear-facing sump of any kind on Titan engines.

Titan engines also feature steel insert crankshaft thrust washers. The original Lycoming design takes thrust loads directly by the parent aluminum of the case, which can gall if run hard before fully wetted during break-in or under very hard loads or extreme time in service. Titan machines their cases to accept the steel thrust washers first seen in Continental 470/520 engines to essentially eliminate this issue.

All Titan engines are statically and dynamically balanced, use roller valve lifters and the customer’s choice of front- or rear-mounted propeller governors. Titan’s two-year or TBO warranty begins when the engine is put in service, not to exceed one year after purchase. TBO is 2000 or 2400 hours.

Continental, under Chinese ownership for years, has benefited from substantial capital investment but the new facilities have come online glacially. Still, Continental says quality is improving and lead times on Titan parts are as short as nine months given how the supply chain wobbles. The good availability of Titan cylinders has been a bragging point the last few years—though they’re only now available as the through-hardened forged steel variety as the NiC3 nickel silicon carbide spec has been dropped. This is denoted by a U in engine model specifications, replacing the T that previously marked NiC3 jugs. An IOX-340-JDD3T8H changes to IOX-340-JDD3U8H, for example.

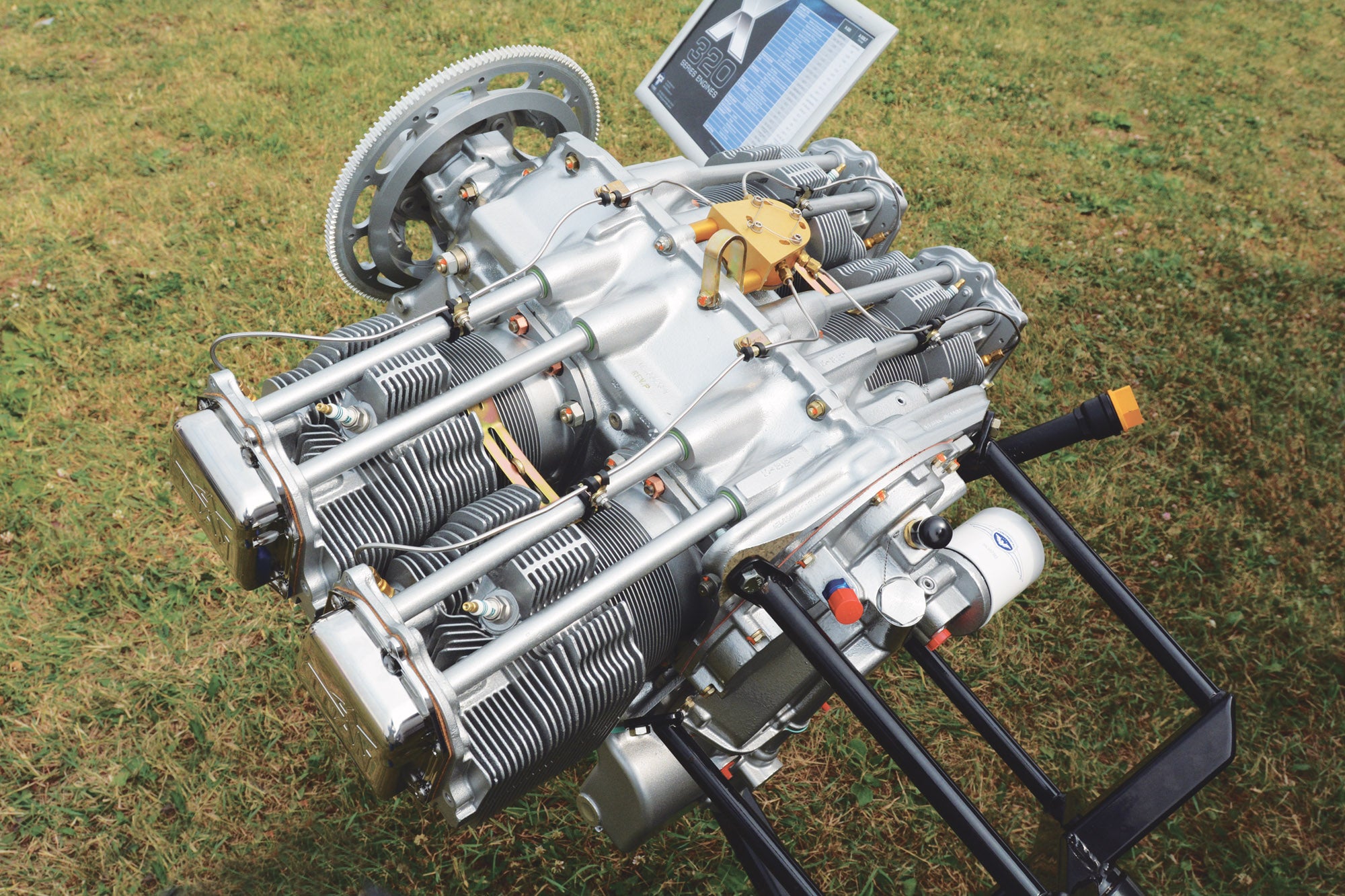

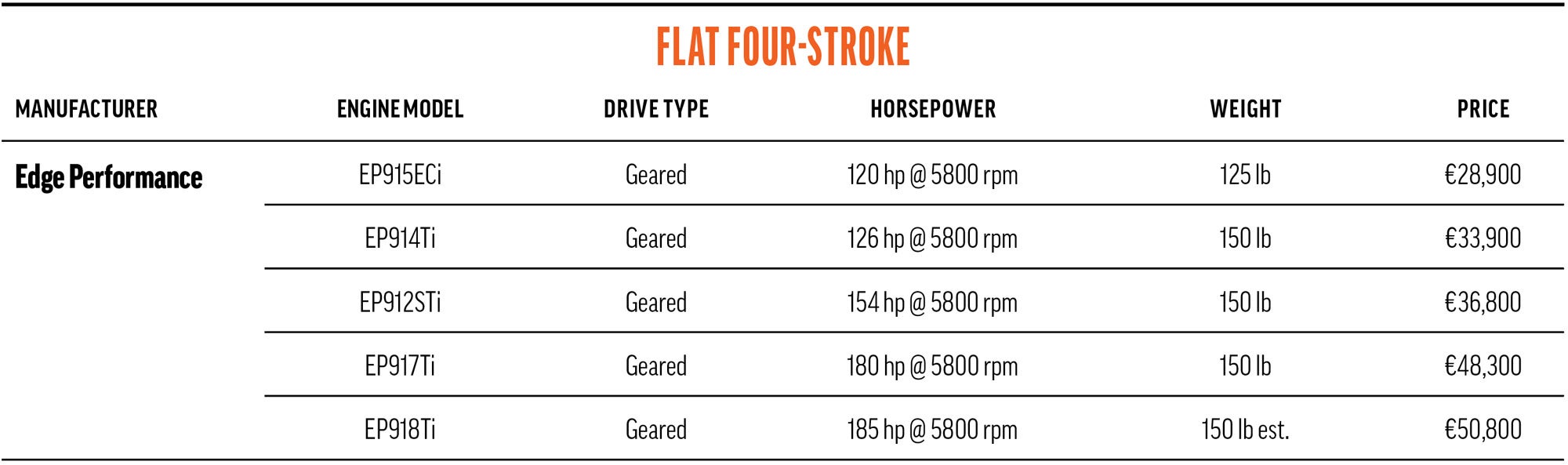

Edge Performance

Taking up where Rotax leaves off is Edge Performance, with headquarters and engineering in Norway and dealers worldwide. Edge engines result from a new Rotax modified with Edge parts and tuning.

Two independent distributors cover North America: Michael Busenitz at STOL Creek Aviation in Whitewater, Kansas, and Jason Busat doing business as BadAss PowerSports in Lacombe, Alberta, Canada. Both focus on hot STOL sport and competition aircraft.

These distributors—and Edge in Norway—combine Rotax components with Edge parts in their own shops to Edge specification, thus reducing international shipping costs. Modifying already flying Rotaxes is part of Edge’s business, as are complete, new-build engines. The number of combinations possible, along with the increased performance and often reduced weight, is impressive as Edge offers big-bore cylinders, tunable computers and wiring harnesses, improved intake manifolds and many other supporting pieces. As expected, big-bore models are especially good sellers.

Also expected was that Edge would offer their take on the Rotax 916 iS: the EP918Ti released in the summer of 2024. Rated at 185 hp for 5 minutes, the new 918 is a more highly fueled and boosted 916, so it starts with all of Rotax’s advanced features.

Specifically, Edge substitutes their airbox, intake manifold, injectors, wiring harness and computer and leaves the rest alone. It’s the most powerful variation on the Rotax theme to date. With 54 inches of manifold pressure at full chat the Edge 918 is dependent on a good intercooler. Because of that, the max continuous rating with this engine can vary but 150 hp continuous is a good nominal figure.

The EP918Ti does not replace the popular EP917Ti, which is still fairly new itself, being released in late 2023. The 917 is just a little behind the new 918 with 180 hp available in a 1-to-1 pound-per-horsepower package, so it puts some real get-along in a Kitfox or the like and is a little less expensive than the 918. Based on a 915 iS Rotax, the Edge 917 is fully electronically controlled, with closed-loop fuel and spark along with CAN bus outputs to support Dynon and Garmin displays. A knock sensor provides detonation protection and the ECU is user tunable. Optional on-the-fly dual-tune software allows switching between 180- and 160-hp settings when reduced boost is preferable; sea level power is available up to 15,000 feet. Delivery with a one-year/100-hour warranty is just four months, says STOL Creek.

If the $50,000+ 917/918 powerhouses are too much, consider the turbocharged Edge 912STi, comparable to the Rotax 915 except it weighs 25 pounds less, has more boost and thus jumps to 154 hp all while retailing for a competitive $42,500.

Three other Edge engines—one naturally aspirated and two turbocharged—deliver much of what the hot Rotax market is after. Of the two naturally aspirated options—the EP915ECi and 916ECi—the EP915ECi is the simplest and least expensive. It’s essentially a 912 ULS Rotax fitted with a 1484cc big-bore cylinder kit and Edge fuel injection to deliver 120 hp while saving about 5 pounds. Busenitz says the fuel injection really transforms the engine, helping to noticeably smooth the idle and quiet the PSRU, plus it gives faster throttle response and typically a 1-gallon-per-hour better fuel burn.

The 916’s larger cylinders yield 1621cc but require case and head machining, so it’s more expensive and mainly seen as a big-bore kit rather than a complete engine.

Edge’s most popular engine is the EP914Ti. Imagine Rotax’s carbureted, turbocharged 914 engine but with fuel injection and 125 hp. Edge builds their 914 off an 80-hp Rotax 912 UL, making it an easy engine for a dealer to assemble as all they need to do is dress the Rotax long block with an Edge turbocharger, exhaust and electronic fuel injection. As a result it can sell it for less than the 914 Rotax.

Key points to Edge engines are true redundancy with dual ECU computers (Rotax uses one computer with dual lanes), the addition of a camshaft position sensor, refined wiring harness and some weight-reduction points around the engine.

Jabiru

Light weight, simplicity, affordability and snappy power-to-weight are defining Jabiru characteristics. On sale for many years, the Australian engine is now in its fourth and easily most robust generation.

The Jabiru’s turning point was the in-depth redesign of its cylinder heads to improve cooling. Now dependable, the fourth-gen Jabiru has continued unmodified into 2025. Construction is heavy on aluminum through the crankcase and cylinders—silicon carbide and nickel coated—for low weight and rapid heat transfer.

Built entirely in Australia, Jabiru ships U.S.-bound engines to their distributor, Arion Aircraft in Shelbyville, Tennessee. Arion says they keep a standing order with Jabiru (who has engines in stock) for two engines and delivery is rapid. Pricing remains stable—and remarkably low—plus Arion supports the engine with a builder-assist program and in-house major overhaul program.

Two engines are offered, the four-cylinder 2200 rated at 80 hp and the six-cylinder 3300 at 120 hp. Both are popular but the 3300 outsells the 2200 around 10:1, according to Arion. The 132-pound 2200 is found in the smaller Zenith and Sonex airframes, Van’s RV-12 and the Titan Tornado. The bigger 3300 is typically seen in the Arion Lightning and larger Zenith, RANS and Van’s models.

Both are simple engines. A single Bing slide-type carburetor, mechanical fuel pump and inductive ignitions are used, along with fixed-timing ignition distributors. Both the alternator and inductive ignition are integral to the engine and both should be working as long as the engine is rotating.

Arion notes that attention to detail when installing a Jabiru is important. Engine cooling and tuning should be done in short, 10-minute flights. Adjusting the baffling and changing carburetor jets are the two main tasks to getting the Jabiru happy; when done correctly expect a 1000-hour TBO for the top end of the engine.

Lycoming

“The story is production,” says industry juggernaut Lycoming. More than busy trying to meet demand and reliant on numerous outside vendors for many of its parts, Lycoming has been fully occupied building its existing engine catalog and has not been designing anything new.

Of course there are a handful of minor technical changes ongoing at any outfit as large as Lycoming, but the push has been getting more CNC machining centers operating and more engines out the door. The high demand means the wait for a new Lycoming still averages well above a year and sometimes half again as long. Order early.

Lycomings are immensely popular largely because they’ve been so well-known in both the certified and Experimental worlds since WW-II. Every A&P knows how to work on them, special tools such as cylinder wrenches are in every maintenance hangar across the world and pilots are well-versed in their operation. They’re the safe choice for insurance, parts availability and resale security. In the Experimental/Amateur-Built world they conquered the all-important RV scene years ago, giving them scale across all of the kit aircraft market.

To compete with the custom engine shops, Lycoming has their own in-house custom Thunderbolt line where two-person teams assemble customer-specified Experimental engines from all-new Lycoming and third-party parts. It is a popular source for enthusiast engines for both performance and aesthetic reasons, even with a price premium. Unfortunately for meeting demand, the Thunderbolt shop is a little smaller than you may think. There are typically just one or two two-man assembly teams working there, and the Thunderbolt order book continues to hold steady at 300 engine builds. Completing about 12 engines a month, the Thunderbolt shop has its work cut out for it.

Thunderbolt engines carry a price bump over stock but include balancing to tighter tolerances, hand-ported cylinder heads, your choice of Airflow Performance or Avstar constant-flow mechanical fuel injection, Lycoming’s EIS electronic ignition, dynamometer break-in and a fair number of paint color choices. From there the extra-cost options are nearly limitless, including custom colors, chrome detailing, high compression pistons and so on. The most common Thunderbolt option is 10:1 compression pistons, with the caveat that 100LL fuel is then required (no mogas). As for the engines offered, Lycoming lists their familiar 235, 320, 360, 390, 540 and 580 cubic-inch designs in their Thunderbolt lineup. That’s every Lycoming save the eight-cylinder 720. As it has been for a couple of years, the 215-hp IO-390 angle valve stroker keeps “selling like hotcakes” as the market looks to muscle up the four-cylinder platform for all it’s worth.

A quick explanation of Lycoming’s engine families centers on the number of cylinders plus their bore and stroke. The 235, 290 and 320 engine families share the same stroke, with the 290 and 320 having larger bores. The 360 and 540 are simply four- and six-cylinder versions of the 320 cylinder bore coupled to a longer stroke. The 390 and 580 share a larger yet cylinder bore on what would otherwise be 360/540 engines. There are two basic cylinder families: parallel valve and angle valve. Parallel-valve cylinders are smaller and lighter but don’t cool as well, limiting their power potential. Angle-valve cylinders are larger and heavier, with more cooling capability, and are used on the highest-power variants.

Oh, there’s more. You will find variations in induction systems. Carbureted engines are usually fitted with a vertical induction at the bottom of the oil sump but fuel-injected versions can have front, rear or vertical induction. Confused yet? There are also variations for single-drive or dual magnetos, aerobatic oiling, vacuum and fuel pump fitments, front or rear prop governor mounting and on and on. This nearly incomprehensible menu is another reason why ordering one through your kit’s manufacturer is a smart move as this should all be sorted out for you.

And as we note every year, to put things in perspective Lycoming holds one major trump card in the time-tested nature of their powerplants. There are so many Lycs flying the company estimates the Lycoming brand accrues 1 million fleet hours monthly.

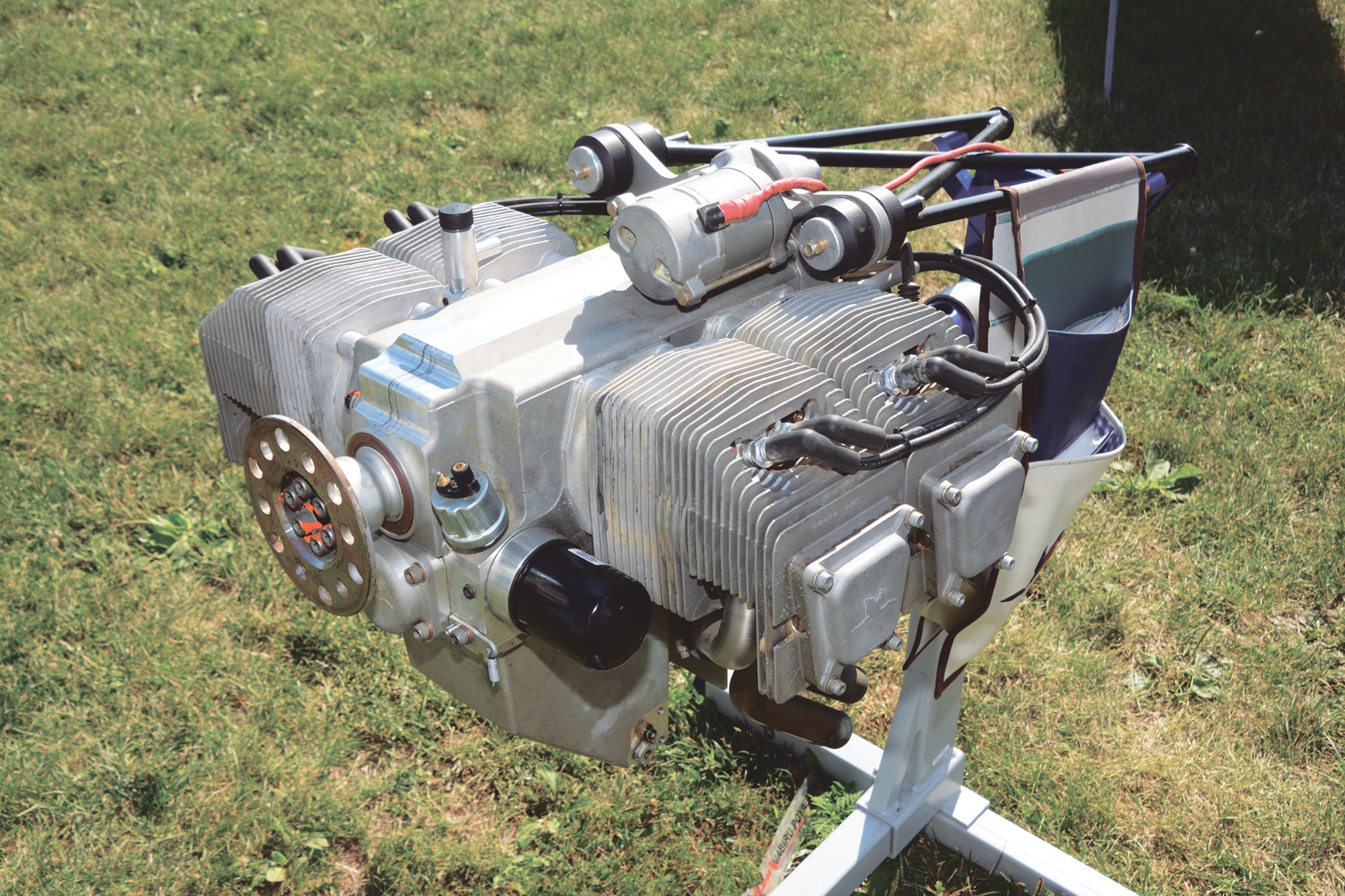

MWfly

Popular in Europe for 21 years with hundreds sold, Italian maker MWfly’s engines are thoroughly modern designs aimed squarely at the light plane market. Big news in 2024 for North America was appointing a long-needed, dedicated distributor, Atilla Gahbro. Based in the Los Angeles area (Torrance), Atilla was growing a set of service centers (Torrance and Ft. Pierce, Florida) along with advertising, social media and fast delivery at our deadline. He’s aiming to deliver in one week if he has an engine in stock and three to four months for the more typical build-to-order scenario.

MWfly engines are organized under three general headings: the blue SKYline for cruising, red REDline for performance and black Turbo line for altitude flying. Physical differences are relatively few and more typically found in computer tuning.

The product of two Italian automotive engineers with Ducati and Lamborghini roots, MWfly engines are horizontally opposed, liquid-cooled, single overhead cam, two-valve, electronically fuel-injected designs with dual ECUs (with CAN outputs). Engine speed runs in the 4000 to 4500 rpm range and while the two lowest-powered engines are direct drive (plus two helicopter-only direct-drive offerings) a PSRU gearbox is typical. Hydraulically controlled constant-speed propellers using MWfly hubs and Sensenich blades are supported on the 122-, 135-, 140- and 160-hp plus the Turbo engines.

A 2022 cylinder head and valve cover redesign gained efficiency for the entire lineup. MWfly gave the upgraded engines the Spirit label to differentiate these Gen 3 engines from their earlier selves and they’ve continued with no internal changes since. In 2024 a turbocharged line was released with 180, 210 and 240 hp. All engines are built in MWfly’s Milan, Italy, headquarters.

Efficiency is high. The 160-hp engine is rated at 1.2 pounds per horsepower—that’s a shade over 1 hp per cubic inch—weighs 191 pounds and burns just 4.5 gph of mogas or 100LL. These are excellent numbers reflecting the design’s modernity. It’s worth noting the 180-hp Turbo engine sports a critical altitude of 20,000 feet, too.

MWfly normally sells their engines without alternators, cooling systems, governors or exhaust. All of these accessories are available as extra-cost options, as are a dual fuel pump module, bed-type engine mounting and CAN interface. Atilla says he’s working on firewall-forward parts/kits as demand dictates.

ULPower

ULPower’s mechanically conservative but electronically contemporary engines are wholly their own design and enjoy wide demand in both lightweight and mainstream Experimental aircraft. After detail improvements last year there are no technical changes for 2025, but it is good to remember ULPower is an ISO9001 manufacturer with ASTM certification on many of their engines and an increasingly strong orientation to OEM engine maker status.

If they seem like an alternative engine maker in the U.S. compared to Lycoming, Continental and Rotax that’s true in numbers of engines sold, but ULPower is no mom and pop engine shop. Rather, it’s a consortium of several Belgian industrial firms. And in a sign of growth, ULPower is seeking service centers in North America to assist on engine installations and maintenance; established technicians and FBOs willing to train at their Florida facility are invited to inquire.

ULPower’s offerings are built around one air-cooled cylinder design and either a standard or long-stroke crankshaft. Arranging the number of cylinders and strokes, along with aerobatic oiling mods and a helicopter variant, has yielded 16 engines arranged in four engine families—the 260/350 small bores and 390/520 big bores. This gives power options ranging from 97 to 220 hp.

Upcoming is the UL350iHPS-C, a vertically mounted, forced cooled, counter-rotating helicopter engine. It’s part of a re-engine package for RotorWay 162F-Exec helicopters and was scheduled for flight testing in January 2025. Pricing will be announced after development, which is in conjunction with the RotorWay service center at Cannon Creek Airpark in Lake City, Florida.

In general ULPower engines are an interesting combination of a traditional horizontally opposed, single-camshaft, pushrod-activated, overhead-valve, air-cooled, direct-drive layout but with electronic engine management—all are electronically fuel injected and sparked. Thus, there is no mechanical fuel pump. A single computer is stock, but dual ECUs are optional with plug-and-play CAN bus interfacing with Garmin, GRT and Dynon.

These engines run most cleanly on 93-octane unleaded gasoline, but 100LL is acceptable. More precisely, since 2023 the UL350i and UL520i have updated ECU mapping allowing 87, 91 and 93 RON mogas, plus UL91 and 100LL avgas.

ULPower does well regarding supply chain issues with eight weeks between ordering and delivery in North America. Core engine parts are made in-house by the Belgium companies. Engine accessories such as the alternator and sensors are automotive or motorcycle parts produced in immense numbers. Like other European makers, ULPower pricing is dependent on the euro-to-dollar exchange rate, so watching the market and planning ahead is good advice.

After 20 years in the market ULPower engines are found on a wide range of airframes and some firewall-forward kits are available. The lightweight RANS, RV-12, Zenith and such airframes were early adopters, with the Belgium engines now being found on all the popular RVs, GlaStar/Sportsman and other practical Experimentals. ULPower engines are also found on UAVs.

ULPower TBO is 12 years or 1500 hours for naturally aspirated engines and 12 years or 1200 hours for the 520 Turbo engine. Furthermore, ULPower says the cost to overhaul these engines is “ridiculously low” compared to the aviation mainstream. A three-year warranty on naturally aspirated engines and one year on the 520 Turbo and aerobatic engines is standard.

One ULPower quirk is their unique engine mount spacing. Thus, Lycoming Dynafocal mount adapters are used on many aircraft. This is a tubing weldment sandwiched between the ULPower mounting plate and a standard engine mount for an RV or what have you. Handily, the adapter also adds the necessary 4 inches or so often required to balance the lighter Belgian engine.

Inline and V Four-Stroke

AeroMomentum

You could call them auto conversions, but AeroMomentum does not start with complete auto engines. They purchase industrial or long-block core engines from big automakers and finish them off as aircraft powerplants at their facility in Stuart, Florida. Suzuki is the source of the 1300 and 1500 engines, while the others are non-Suzuki and cannot be revealed as part of the sourcing agreement. Engines are built from all-new parts and are modern, water-cooled, four-valve, high-efficiency designs featuring high rpm and a gearbox.

AeroMomentum has their own PSRU, engine management, coolant plumbing, electrical system and mounting hardware—along with some firewall-forward kits. Internally there are cast-steel cranks, forged connecting rods and knock sensors; externally there’s Bosch engine management, sequential fuel injection and 65-amp alternators.

Things have been busy at AeroMomentum with growth in the sport market along with much new business in more corporate/governmental endeavors, much of it overseas. Thus, for 2025 AeroMomentum’s lineup continues with a 1.0-liter three-cylinder, 1.3- and 1.5-liter four-cylinder and a turbocharged 2.0-liter four-cylinder.

There are more variations than we can list in the specification table of the AeroMomentum engines because the 1.3- and 1.5-liter four-bangers can each be had in upright or heavily canted form, with either traditional Lycoming-spaced aft or AeroMomentum bed mounts, standard or high offset gearbox, plus each offers three states of tune and turbocharging. The upright or canted options are strictly for packaging ease in different airframes and make no difference in power output (but do slightly in price). The power differences come from either stock engines or those with AeroMomentum’s more aggressive camshaft and head work. Most aft- or bed-mount engines fit under cowlings intended for Lycomings or Continentals, plus upright engines with large offset gearboxes fit under Rotax cowlings. Confirm your specifics with AeroMomentum, of course.

All AeroMomentum engines use a helical, spur-gear prop reduction gearbox. It features custom 8620 alloy gears and, like many of AeroMomentum’s other parts, is designed in-house. (There’s no lack of engineering experience at AeroMomentum with Cal Poly, Harvard, UMass Lowell and NASA in the résumé.) Parts are forged, machined, heat-treated and otherwise produced by out-of-house vendors then assembled at AeroMomentum.

AeroMomentum also offers various firewall-forward supporting parts such as engine mounts and cowlings, plus their Aero-Graph engine monitor.

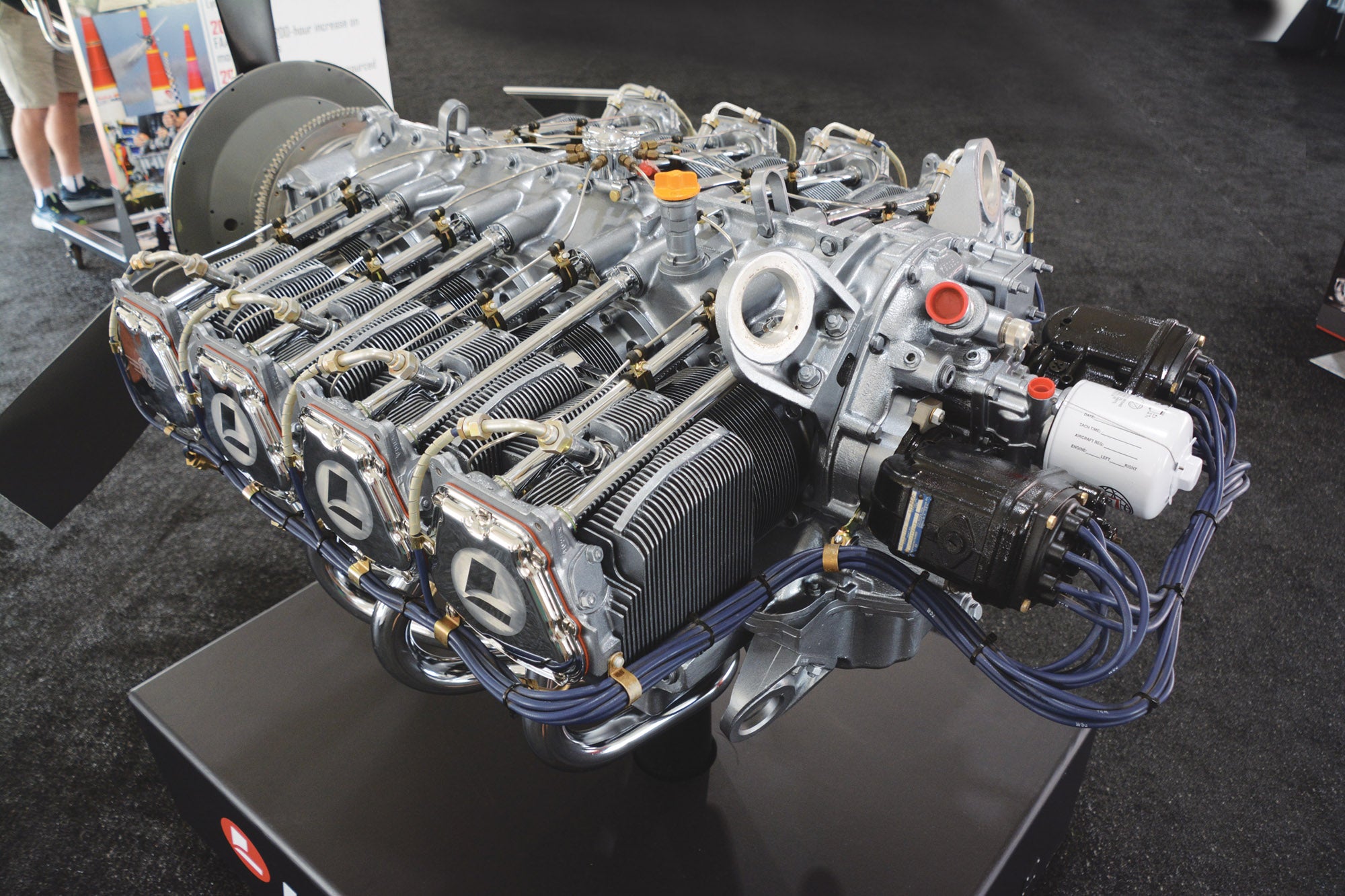

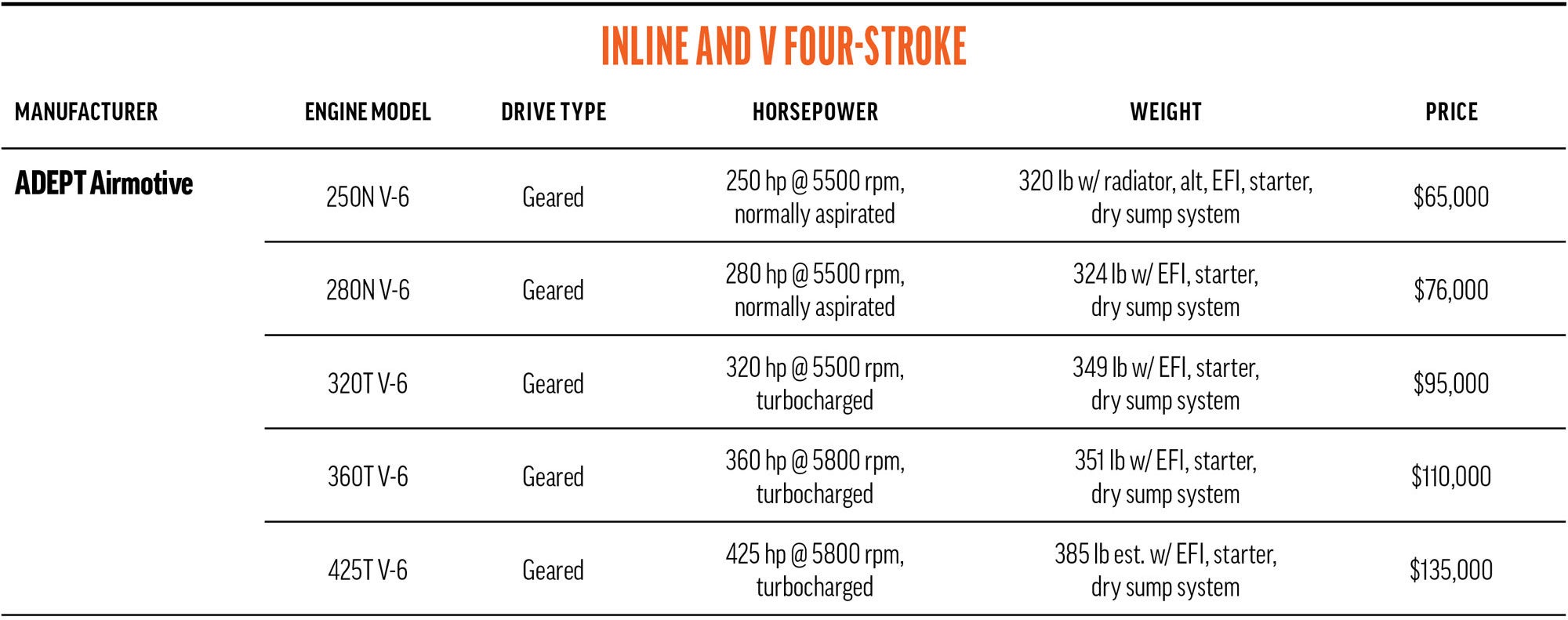

ADEPT Propulsion Technologies

A South African company, ADEPT has been very slowly bringing an all-new, liquid-cooled piston engine to market. Their clean-sheet design V-6 features an unusual, nearly flat 120º bank angle, 3.2 liters (195 cubic inches) displacement and FADEC engine control. A knock sensor allows nearly any fuel, from 100LL to mogas laced with ethanol or methanol. Other features are dry sump oiling with piston squirters, billet crankshaft and connecting rods and forged pistons. The same bore and stroke are employed across several power levels, the differences being in the camshafts, injectors, computer mapping and other tuning factors. Turbo’d engines use a single turbo.

Power is rated at a base, naturally aspirated 260 hp, then through several steps to 360 hp in turbocharged form. A 425-hp version was added for 2024 and will be built upon the first customer order. The 300-hp naturally aspirated engine has been deleted from the advertised lineup because it is so close to the 320-hp turbo engine, but ADEPT can deliver the 300-hp engine if desired.

ADEPT delivered a handful of engines to the U.S. for well-heeled, fast-glass aircraft customers and some of those projects are nearing flight. ADEPT’s North American representative Lee Brinley has a Lancair ESP that could make AirVenture 2025; likewise a customer Velocity SE is also in progress.

Naturally the ADEPT V-6 offers the usual liquid-cooled advantages and is a foot narrower than a 550 Continental so reduced frontal area is possible. Of course, when making a new narrower cowling integrating a radiator is also required, but all told those flying high and fast could find advantages here. Not recommended for the casual kit builder, the ADEPT is an option for early adopters with the means to support something new.

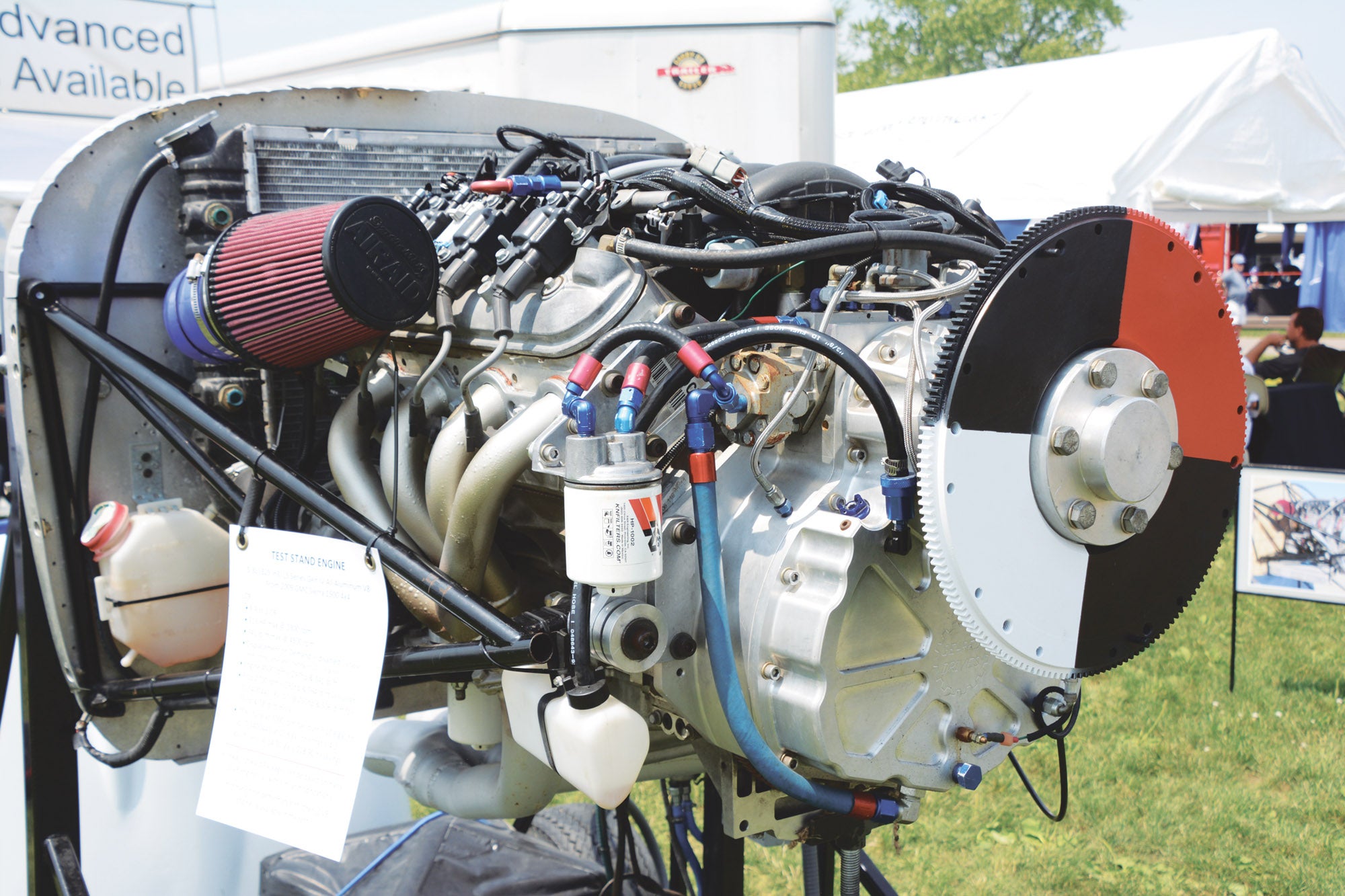

Auto PSRU’s

Auto PSRU’s is not a traditional engine manufacturer; they make spur-gear with centrifugal clutch propeller speed reduction units. However, on a boutique basis they’ll help customers develop a very complete firewall-forward fitment using one of their PSRUs.

These days their focus is their PSRU and a Chevy LS3 for RV-10s in three states of tune, all of them muscular. The entry level is a 375-hp at 4500 rpm LS crate engine mated to their PSRU and everything else (centrifugal clutch, fuel injection, ignition, alternator, cowling and so on are included) for $72,500. Thanks, inflation. But at least the Chevy crate engine takes only three weeks to arrive at AutoPSRU’s.

Previous Subaru packages are essentially discontinued due to a lack of suitable engines; likewise, their Mazda 13B rotary engine kits are for all practical purposes dead. These were typically a coproduction with Atkins Rotary/American Rotary in Oregon; see the “Circling the Airport” sidebar.

If a customer has a Mazda or Subaru engine and wants just the 250Z gearbox, AutoPSRU’s can supply them for $19,900—same with their 300Z gearbox with a 7.0-inch vertical offset for use on small V6 or inline engines up to 320 hp. It’s $22,300. AutoPSRU’s can help with the entire firewall-forward engineering if fitting either of these gearboxes.

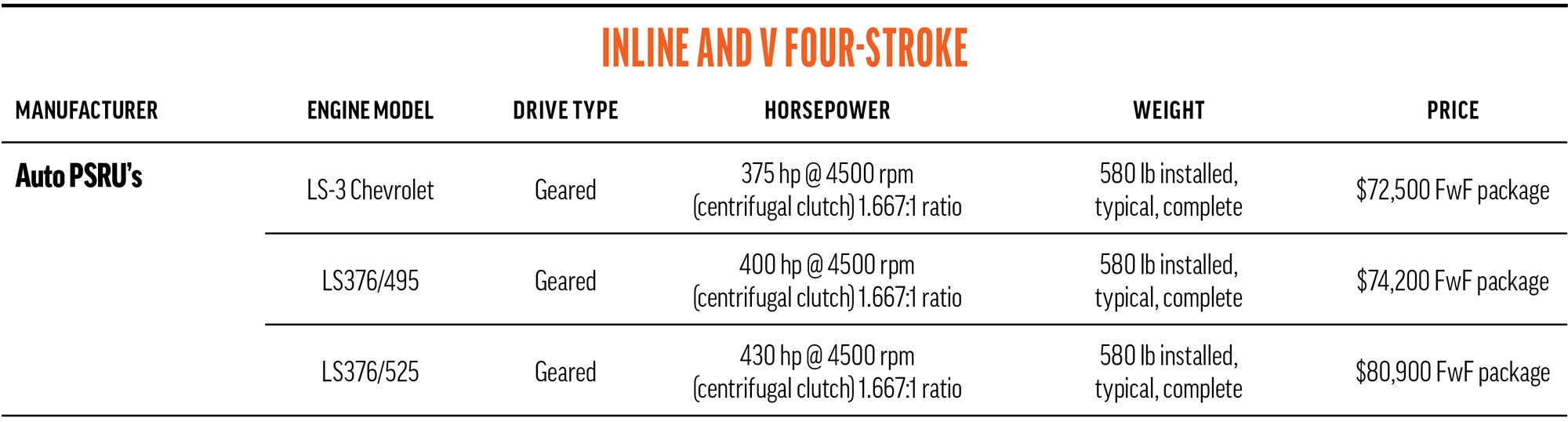

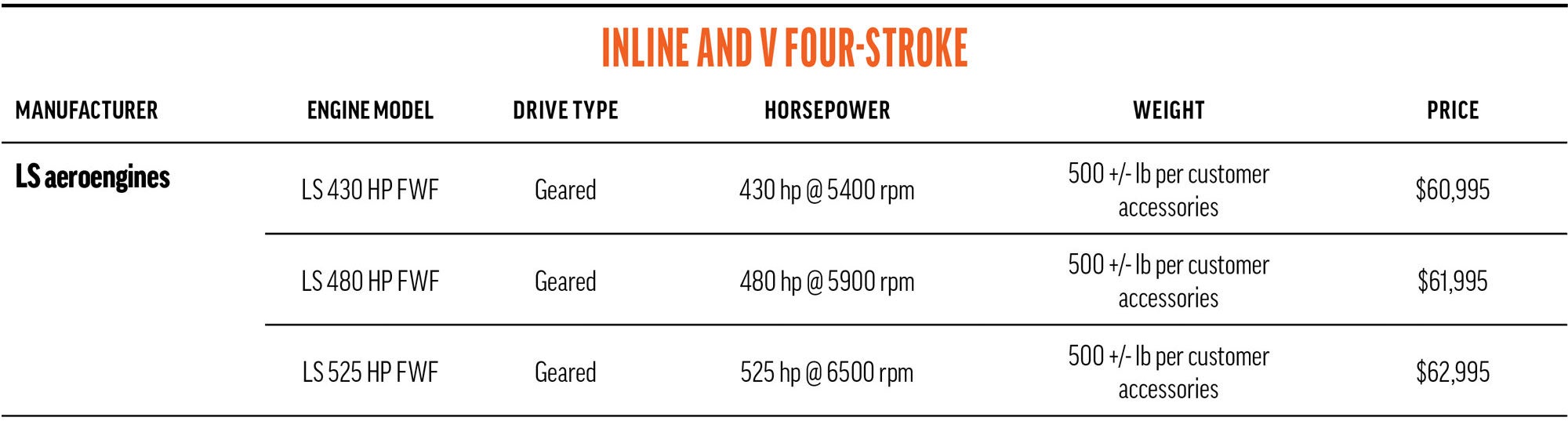

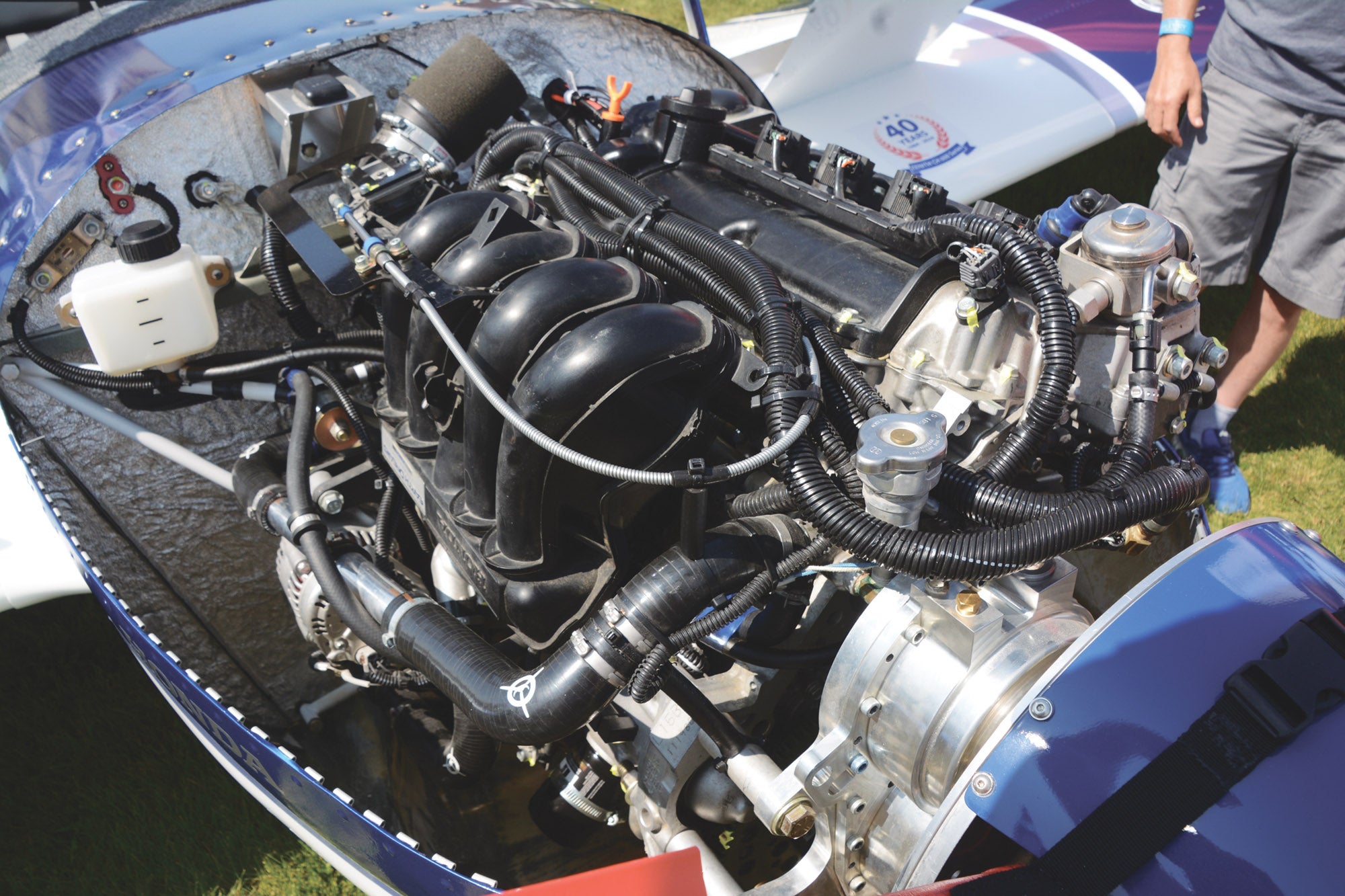

LS aeroengines

Performance for the dollar is what made the American V-8 popular and that’s still true when bolting one of Detroit’s finest onto an airplane, such as a Chevy LS3 in a Murphy Moose as practiced by LS aeroengines (see also Moose Mods). They offer three models built around a GM factory-new crate LS3. All are naturally aspirated with a helical gear PSRU to deliver wicked torque to the prop hub. They work with customers to mount their V-8 on other airframes, too.

The entry level here is 430 hp, which does a Moose just fine, backed by a 480-hp tune for the guy wanting more and an eye-watering 525 hp for use with floats. The LS3 engines are stock from GM, with the important exception of LS aeroengines’ camshaft said to optimize durability and a flat torque curve in the 4000–5000 rpm range.

Though experienced with the Moose airframe, LS aeroengines is new as an engine supplier. At our deadline they had perhaps five LS engines flying with another six scheduled to take flight in 2025 and the highest-time engine had 250 hours on the Hobbs. LS aeroengines reports great performance. In a Murphy Moose with 31-inch tires 2000 fpm climbs are routine and the 172 mph cruise burning 15 gph runs away from the Lycoming or MP-14 competition.

Still, the LS conversion is compelling with many advantages. First is cost; the mid-$60,000 range is excellent value for over 400 horsepower. Only the MP-14 radial makes more torque at the prop and the LS conversion needs less maintenance and surely won’t have the Romanian’s oil appetite. Liquid cooling means no shock cooling for unlimited ascent/descent profiles and no excuses for not having cockpit heating. Feed it a range of fuel: ethanol-free 93 (best performance), 91 octane pump gas (again, ethanol free) or 100LL are not a problem. Weight is claimed within 10 pounds of an angle-valve 540 Lycoming so weight and balance works in many airframes. Plus LS aeroengines is forecasting 2000-hour TBOs. Replacement likely makes sense: Simply get another (relatively inexpensive) crate Chevy rather than rebuild.

Supply chain issues are minimal as the supply of LS3 engines is essentially unlimited. Volume PSRU production was being sorted at our deadline meaning a three- to four-month delivery time. A 60-day delivery time is the expected norm once PSRU supply catches up.

LS aeroengines uses SDS electronic engine management. This means electronic ignition and fuel injection and no traditional mixture knob. There is a rheostat knob for fine-tuning the SDS fuel delivery but normal operations require no mixture attention from the pilot. Likewise there are no special requirements propeller-wise as the PSRU hub accommodates standard props. Most LS aeroengines customers on wheels obtain a used Hartzell or MT three-blade in the $15,000–$18,000 range while the float pilots opt for a four-blade, reversing MT, a sobering $40,000 proposition. An idler gear in the PSRU means direction of propeller rotation is normal.

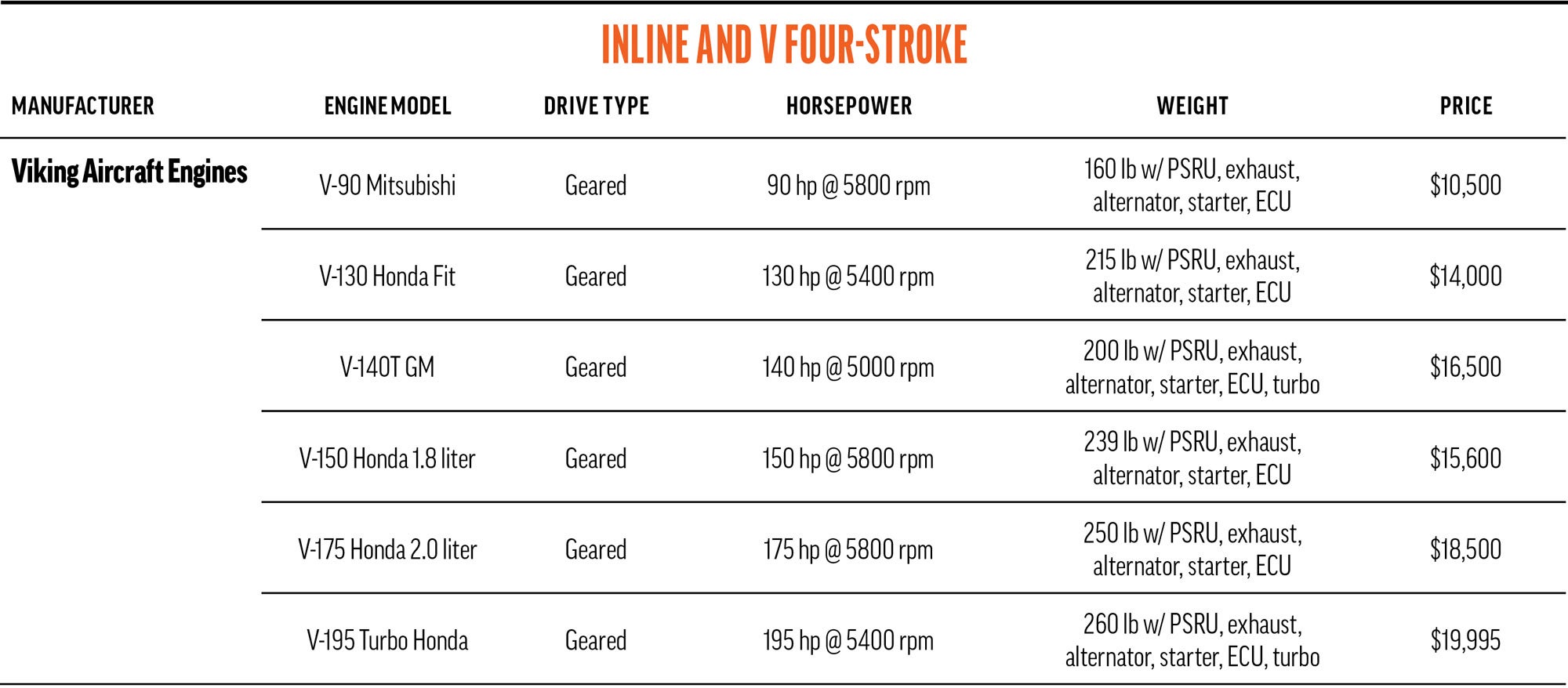

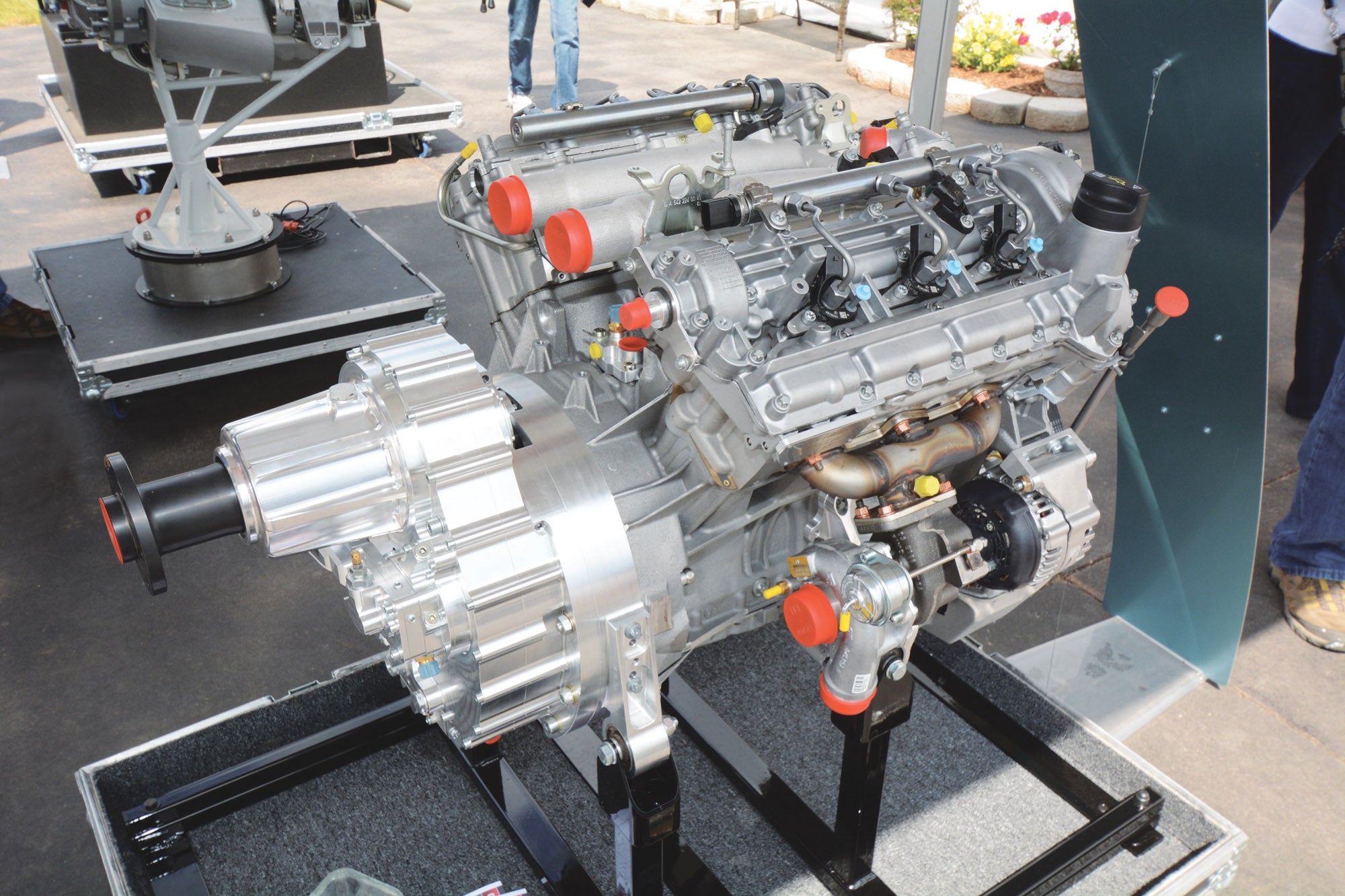

Viking Aircraft Engines

Viking has a unique place in the engine market. Citing the mechanical superiority of contemporary automotive engines, they buy used Japanese and domestic auto engines and convert them to aviation use.

Their chief enabler is their own gearbox with a 2.33:1 gear ratio along with a catalog of over 45 firewall-forward kits fitting especially Zenith and RANS, plus Sonex, Kitfox, Murphy Aircraft, Van’s, GlaStar and others. Given the low cost of used engines, Viking leverages that into some of the least expensive engines in the Experimental neighborhood, and “overhaul” costs are bargain basement as well. It’s simpler and less expensive to replace these engines than rebuild them.

Viking’s entry-level offering is a 90-hp version of a three-cylinder, DOHC, 12-valve Mitsubishi. Fitted with Viking’s own gearbox (climb or cruise gear ratios can be ordered; it can also work in pusher applications), the combination weighs just 159 pounds and posts a particularly muscular low-end torque curve when augmented with the lower of the two gear sets. This engine is aimed particularly at the Zenith CH 701.

One twist of using auto engines is Viking by necessity changes its engine lineup as the engines become available or fade in number. Thus, the earlier 110-hp engine is no longer available, but in late 2023 Viking added the V-140T and V-175. The V-140T is the 1.2-liter three-cylinder turbo found in the Chevy Trax, Trailblazer and Buick Encore and slots between Viking’s 130- and 150-hp Honda offerings. The 140-hp GM engine is direct-injected, spins a balance shaft and supports a constant-speed propeller. That strongly promotes more relaxed and fuel-efficient cross-country cruising as the rpm can be lowered while maintaining boost at altitude. Viking sells this engine with gearbox (PSRU), integrated exhaust manifold, computer, wiring harness and starter for $16,500.

For its fast-selling 130-hp engine, Viking starts with the direct-injected Honda Fit four-cylinder powerplant. Geared and with unexpectedly good low and midrange thrust, the combination weighs 220 pounds. Because the Fit engine has its exhaust manifold integral with the cylinder head, the engine is not a good candidate for turbocharging, but the gasoline direct fuel injection gives in-cylinder cooling allowing a high 10.8:1 compression ratio for increased efficiency. By venting crankcase blowby to the atmosphere, Viking escapes the valve deposit issues commonly found in automotive GDI applications.

The 150-hp, 1.8-liter engine is another Honda four-banger. It uses port fuel injection and has gained considerable popularity because it offers a 20-hp bump for just 24 more pounds and not that much more cost than the Mitsubishi 1.3 liter.

The V-175 is a considerably larger 2.0-liter Honda Civic/HRV four-cylinder and is Viking’s second most powerful engine. Viking rates it at 175 hp at 5800 rpm and sells it also with gearbox, exhaust manifold, computer, wiring harness and starter for $17,500. This has to be the cheapest 175 hp in aviation. Because it is naturally aspirated, the V-175 is a popular and easy installation because there is no charge cooler to plumb or hot turbo under the cowl.

Viking’s top offering is the 195-hp version of the turbocharged Honda Accord engine. Naturally, this also gives a fat low-end torque curve (there’s nearly 440 pound-feet of torque at the prop at only 1250 rpm). This engine is also augmented by Viking’s gearbox and Honda’s gasoline direct injection. Weight naturally rises to 260 pounds but either 100LL or mogas can still be run. As with other small-displacement, liquid-cooled engines, Viking specifies lead-scavenging additives with these engines if run on 100LL avgas.

Radial and Rotary

Classic Aero Machining

For those seeking an authentic, full-gyroscopic rotary experience, New Zealand-based Classic Aero Machining (CAM) has developed brand-new seven- and nine-cylinder Gnome Monosoupape engines. They are faithful continuations of the Gnome used in many French, English and German aircraft just prior to and during WW-I.

While using original plans and remaining incredibly period correct, CAM has made some welcome improvements to this 115-year-old design. These include a pre-start oil priming system and lengthening the lower portion of the cylinders for improved piston support. The induction ports are now angled, promoting in-cylinder swirl for better fuel atomization and reduced plug fouling, a big help there. The in-cylinder motion is further aided by CAM’s fuel pump (the originals relied on gravity). Finally, there is an electric starter.

The new seven-cylinder produces 100 hp at 1150 rpm; the nine-cylinder makes a muscular 125 hp and nearly 600 pound-feet of torque while whirling at just 1120 rpm. Interestingly, the seven-cylinder is getting considerable interest likely because it was used on more docile designs while the nine-banger was in some rather spicy jobs, such as the still-not-for-beginners Sopwith Camel.

The CAM story is augmented by KipAero in Dallas, Texas. KipAero offers their own line of uber-authentic continuation WW-I Sopwith airframes using the CAM rotary and works very closely with the New Zealand firm.

Motorstar NA

Few homebuilts can take all the muscle a Soviet-era 621-cubic-inch M14 radial can dish out. But hang-on-the-prop sport pilots and Murphy Moose drivers need all they can get. For them, the Romanian-built M14 provides the huge torque and long-prop compatibility they’re looking for.

The venerable supercharged 360-hp M14 radial is a Russian design built in Romania by Motorstar. Today Motorstar supports the M14, but a few parts are tough to source and Russian embargoes mean Russian parts cannot be exported. Therefore, Motorstar now builds those parts, adding to the cost.

Motorstar M14 engines and parts are imported to North America by Cliff Coy at Coy Aircraft Sales in Swanton, Vermont. Longtime importer and Cliff’s dad, George, has retired.

Coy Aircraft offers overhauls via shipping core engines to the Romanian factory, which includes all rebuild work, a test run and warranty. This is the typical method of obtaining a fresh M14 as factory-new engines are expensive. A factory PF conversion, easily done at overhaul, raises power to 400 hp.

Given the recent rise in domestic engine prices the M14 is becoming a serious horsepower-per-dollar choice. Coy Aircraft offers the engine in the $50,000-$60,000 range depending on a few options (electric starter, prop flanges, alternator voltage, etc.) but rebuilds are much less expensive.

Alternately, Barrett Precision Engines in Tulsa, Oklahoma, has their own rebuilt/upgrade program for these engines using a three-ring piston, higher compression ratio, electronic ignition and fuel injection to yield 440 hp at 2900 rpm.

Rotec Aerosport

Rotec radials are naturals for the vintage round-motor look in light aircraft. The Australian company offers two nearly identical compact radials, the smaller R2800 measuring 172 cubic inches and the larger R3600 with 220 cubic inches. These are a good fit to smaller airframes popular with scale replica builders or Light Sport Aircraft. There are no changes to either engine for 2025.

The 110-hp R2800 uses seven cylinders; the R3600 employs nine of the same cylinders and is the better-selling version. It puts out 150 hp at 2350 propeller rpm (both engines use a 3:2 PSRU gearbox, so that’s 3525 engine rpm). Neither is supercharged and while the R2800 is well-paired with a 76-inch propeller, the R3600 can handle 90-inch props. Because the Rotec is fitted with a collected exhaust with two outlets, the combination of higher rpm and collected exhaust results in a smooth, medium-tone exhaust note similar to a small V-8 turning cruise rpm.

Standard Rotec induction is a simple Bing slide carburetor, but Rotec’s own—and still stone simple—TBI Mk 2 throttle-body fuel injection is optional. Its main attraction is staying on the job during aerobatics. Besides fitments for their radials, Rotec does a brisk business offering versions of their fuel and ignition accessories for everything from VW conversions to Rotax, Jabiru and even Lycomings.

Like all radials, the Rotec scavenges oil to a remote tank and Rotec offers fabrication of such tanks to fit customer aircraft as an optional extra. After 25 years on the market, the Rotec has been mated to a large number of airframes, so it’s worth checking with Australia about a tank before assuming you’ll have to fabricate your own.

Verner Motor

Relatively new Czech engine maker Verner Motor has had a great start—their generous-displacement, slow-turning, non-geared radials offer the sort of long prop, deep rumbling that makes round-motor fans a little weak in the knees. A good customer service reputation and help with installations haven’t hurt, either.

Verner offers a five-radial lineup ranging from three to nine cylinders. All use the same two-valve, 3.62×4.02-inch cylinder, but fit five, seven or nine of them as power needs rise. Designed for 93-octane U.S. or 95-octane European premium mogas, these Scarlets span a 32-inch diameter and carry a 1000-hour TBO (expected to rise with increased experience). Experience shows some lead fouling on a steady diet of 100LL fuel, but this responds favorably to lead-scavenging additives or simply by running mogas.

All Verners employ S&S Super G carburetors, with higher altitude customers typically opting for a Marvel-Schebler carburetor from Verner to obtain a conventional mixture control. The Harley Davidson oriented Super G carburetor is altitude compensating up to Denver altitudes, but above that it runs out of adjustability bandwidth. Alternatively, a few customers have made their own custom single-point fuel injection systems via Airflow Performance and Brahn Sport, but that’s not a factory option like the Marvel-Schebler.

In 2024 all Verners gained the case layout to use the same (and superior) engine mount spacing and mounting “biscuits” the seven- and nine-cylinders have had. This simplifies making engine mounts and avoids some of the vibrating hard-mounts some builders used with the smaller engines.

The 200-hp, 11-cylinder engine Verner fans have been talking about remains in the distance. The factory is so busy meeting demand they haven’t had much time to develop the new engine.

Finally, while Verner sales came to an instant halt at the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, they have rebounded and production has not been hampered by the conflict. Verner’s U.S. dealers are Scaled Birds (also offers interesting replica airframes), Myers Aviation and Brahn Sport Aircraft (extensive design and fabrication capabilities). Pricing is unchanged from last year.

Compression Ignition (Diesel & Jet A)

Continental

Thanks to their complex and high-pressure nature, diesel (Jet A-burning) piston engines are premium devices full of expensive parts, and their penetration into the amateur-built world is essentially nonexistent. Some sophisticated, powerful and very fuel-efficient Jet A reciprocating engines such as the R.E.D. V-12 and exciting but stillborn Graflight V-8 have been developed, but their high purchase price and their makers’ reticence to sell to individuals due to the complexity of properly integrating them into an airframe mean they’re really not in our game.

Meanwhile, Continental has a surprisingly well-populated line of certified diesels as they’ve bought diesel programs started by Thielert, Austro and other European outfits. At least technically these engines are suited to larger homebuilt aircraft (they’ve been used on Cessna 182s, for example), but their economics make them viable only after flying multiple thousands of hours, not the typical sport plane operating profile.

Air-Cooled Volkswagen

The air-cooled Volkswagen aero conversion community shares many characteristics. Obviously they are all built from the VW Type-1 engine, even if some have been upgraded to the point where there are no original VW parts in them.

This means all VW conversions offer compellingly light weight, impressively low costs due to overwhelmingly favorable economies of scale, an upper limit of about 100 hp and a customer base interested in maximizing these characteristics. These are also well-sorted, mature engines as the conversions have been developed for decades; technical changes are now rare. It’s also something of a world unto itself, including common sources of VW parts.

Another shared characteristic is almost all VW aero engine conversions are sold as kits. This saves both the engine manufacturer and the customer money. The one outlier is the original VW aero converter and elder statesman of hot-rodded air-cooled VWs, Revmaster. They assemble and ship their engines as ready-to-run powerplants, something to keep in mind when comparing prices.

AeroVee

AeroConversions, maker of the AeroVee engine, is the piston engine division of Sonex aircraft. A busy, pocket-size aircraft manufacturer producing everything from gliders to single-seat jet sportsters and government UAVs, Sonex’s original core is a series of airframes designed for air-cooled Volkswagen power. Now mature designs, there are no technical changes to the resulting AeroVee engines for 2025.

There are two AeroVee engine kits, the 80-hp 2.1-liter naturally aspirated engine along with a turbo version rated at 100 hp. A turbocharger water cooling system was introduced six years ago and is a near-universal option on the 100-hp engine thanks to its transparent-to-the-pilot electronic control. AeroVee’s laser-cut baffle system and AeroInjector slide-throttle carburetor are also popular, and existing AeroVee owners can upgrade to the turbo with a $4,200 kit.

Hummel Engines

Supplying Hummel Aircraft with engines is clearly the main business here, but Hummel Engines also does plenty of business building four- and mainly two-cylinder VW-based engines for the rest of the hobby. Plus, now that Great Plains has shut down, Scott Casler at Hummel has been supporting those customers as well. Thus, Hummel is the best source of Great Plains parts as long as they last.

Otherwise business has been solid for Hummel. There is a backlog on engines to be built and Casler is shipping them as fast as he can build them. Parts supply is good, with occasional hiccups. Where used engine cases were once popular for the two-cylinder engines, for example, the availability of usable case cores is sufficiently thin that Hummel is using new cases almost exclusively—and the current prices reflect that change. And while VW parts were out of production for a while, Motorav in Brazil has bought the rights and has them back in production. The same goes for bearings.

Hummel’s offerings favor basic, lightweight, low-power builds beginning with a bare-bones 35-hp, 85-pound, two-cylinder bereft of starter or second magneto. The top Hummel is a fully optioned 85-hp four-cylinder with starter, dual ignition and alternator.

Revmaster Aviation

Easily the most experienced VW engine house with nearly 4000 engines built, Revmaster has been building hot VWs for cars and airplanes since 1959. They cater to the better-equipped end of the VW market and sell their engines assembled and not as kits.

Their bread and butter is the R-2300 (2331cc, 142.2 cubic inches). Takeoff power is 85 hp at 3350 rpm; the continuous rating is 82 hp at 2950 rpm. Now a well-sorted combination backed by all sorts of aviation and uber-high-output automotive testing, the naturally aspirated R-2300 uses Revmaster’s own cylinder head and bristles with internal upgrades. These include a four-bearing crankshaft, the unique ability in the VW market to support hydraulically controlled propellers, an eight-coil/eight-spark-plug dual CDI ignition, dual 20-amp alternators and a simple, slide-type, floatless Rev-Flo carburetor.

A turbocharged version of the 2300 is finished and can be purchased but still hasn’t flown. It’s rated at 102 hp at 3200 rpm up to 12,000 feet. Call if you’re interested in taking this one airborne.

Jets & Turboprops

PBS Aerospace

Even with all the recent interest in small turboprops, there is but one place to burn kerosene in the build-it-yourself world. The SubSonex single-seat jet is the one available airframe and the Czech PBS TJ100 turbojet is the one engine that airframe is designed for. It’s the only jet engine in production with the thrust, size and availability to fit the sport aviation bill.

PBS does not disclose technical or pricing information without a nondisclosure agreement, so we’re unable to report directly on the little jet. SubSonex builders can order the PBS engine from Sonex, which lists the PBS engine on their website with full supporting hardware for $75,000. And if you have something spectacularly brief in mind, the TJ100 is available in a higher output version with a 100-hour TBO. Bang!

Corvair

Azalea Aviation

Bill Clapp at Azalea Aviation offers Corvair engines as a sideline to his main business, Saberwing aircraft. Those planes use his 100- and 120-hp Spyder Corvair engines.

The naturally aspirated 100-hp engine is built from reconditioned GM parts reinforced by a steel front hub on the crankshaft, an added front main bearing, nitriding, a 30-amp rear-mounted alternator and new service parts. The 120-hp version gets a new, counterweighted stroker crankshaft yielding 3.1 liters and without cutting the case for overly large cylinders.

Azalea took a direct hurricane hit in late 2024 with two-thirds of one shop roof gone and another hosting a tree, so there has been disruption. But sounding resilient, and anticipating a stronger economy in 2025, Clapp hasn’t raised prices this year.

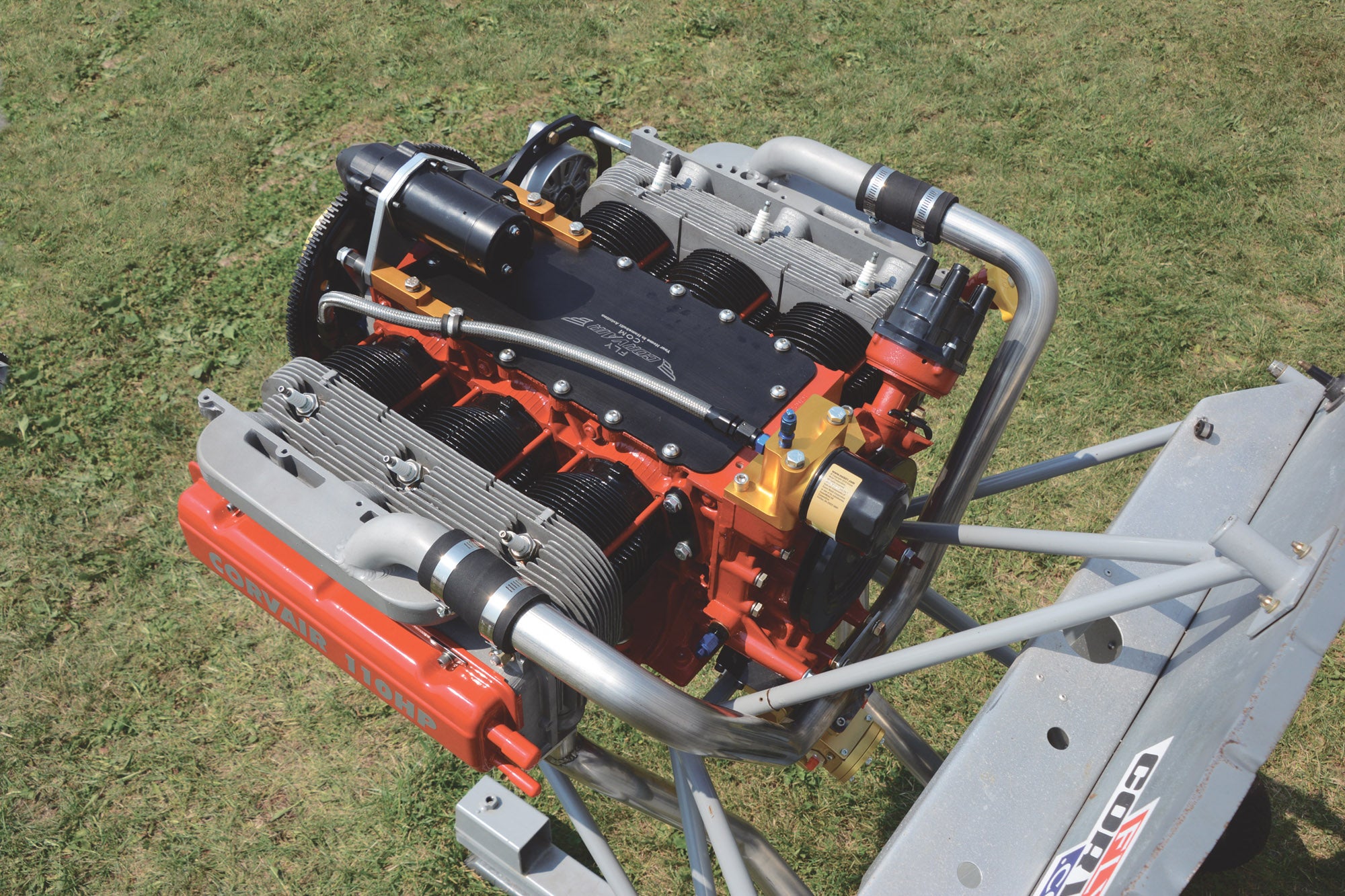

Fly Corvair

The must-visit Corvair shop is Fly Corvair where William Wynne holds court. The outspoken force energizing Fly Corvair, William has made flying Corvairs his life’s calling for the past 35 years.

Wynne developed a variety of Corvair engines but set them all aside in favor of one: the 110-hp, 2850cc version. “It’s the main engine I am promoting as the best combination of quality and still good value. It offers all the good tech improvements, such as Ross pistons and other advances, but doesn’t have the high-end costs of recent years. As a complete kit with carb, ignition, starter and so on it’s $14,250. If you want it assembled it’s $15,250.”

Building a single engine is also more efficient. For example, all pistons are machined to the same weight, so single-cylinder repair kits are kept boxed on the shelf for immediate delivery. Customers can buy one or six of these repair kits knowing engine balance won’t change; the parts simply need to be installed.

Wynne, a consummate storyteller and communicator, is ready to offer his expertise and shop to those wanting to assemble their own engine under his supervision. You can even run the finished engine on his test stand. He also offers a wide range of engine manuals, supporting pieces such as intake and exhaust manifolds, cowling parts and propellers, plus he gives many talks and is a genuine supporter of the builder community. He’ll tell you how the Corvair engine’s niche is offering a user-friendly, affordable, low-frills path to aviation and not to overcomplicate things.

Sport Performance Aviation

Dan and Rachel Weseman own Sport Performance Aviation (SPA), maker of the Panther sport plane powered by Corvair engines, among others. They have always worked closely with Wynne at FlyCorvair for their Corvair engines but do offer two large-displacement versions of their own along with a fifth bearing kit for increased crankshaft support.

The larger displacement engines are either a 120-hp 3.0 big-bore or a 125-hp 3.3-liter big-bore and stroker combination. The latter uses a billet stroker crankshaft. Both of these engines are premium, higher-powered options selling for considerably more than the standard displacement engines from Wynne. They are normally shipped unassembled, but SPA will assemble just the bottom end of the engine for $895.

Just a heads up, there IS a plug-and-play electric motor package in the kit market, at least for lower power applications:

https://www.geigerengineering.de/en/avionics/products

It’s flying in a few ultralights like the Elektra Trainer but I’m pretty sure they also sell to individuals.

Tom: Bravo Zulu!

I can only guess how much work goes into assembling a snapshot of aircraft engines, or to telling a long, interesting story; you do both while telling the truth.

Thank you very much for this reference.

Ron

Wankel, what about Wankel RCEs? There are several offered. Microturbines? PulseJets? Lorin RamJets?

Thanks. Blessings +

This is one of the most useful kit planes articles on the Internet. Rather than putting all the information in one long page it would be more useful to separate it by engine category like you did in previous years. Thanks