Aluminum is usually marked by the manufacturer to indicate the alloy and temper. The markings may also include the lot number and the born-on date.

Ford Motor Company recently advertised their new line of truck bodies as being made of military-grade aluminum. It’s a new twist on the old hype: made of aircraft-grade aluminum. I suppose the salespeople figure: What could be better than aircraft-grade (or military-grade) aluminum, right? After all, you wouldn’t want a truck body made of beer-can aluminum, would you?

Actually, beer cans are made from 3000 series aluminum, which is an alloy that is commonly used in many aircraft/military applications. In fact, look in any reference book, technical specification, or aluminum application guide, and you’ll find almost the entire spectrum of aluminum alloys are used, one way or another, in the aircraft or aerospace industry. Wheel axles are made from 2024, wingspars of 2024 or 6061-T6, hydraulic fittings from 2011. The alloys 2017, 2024, and 2117 are used to make rivets. Got a piston engine? The pistons were likely forged from 4032 or 2618. 7075 is a favorite for structural components because it’s as strong as many steel alloys and machines beautifully.

Machinery’s Handbook (27th edition) lists more than 70 common wrought-aluminum alloys in seven groups (1000 series to 7000 series). The groups are ordered by their principal alloy element, with the 1000 series being primarily “pure” aluminum. The principal alloy for the rest of the groups are:

Even within the particular alloy groups, some are bendable, some are not. Some are readily weldable, others not. Some have really good machinability, some barely tolerate machining, and some don’t machine at all with traditional machine tools. Heat treatment can dramatically alter the working characteristics of an alloy. 6061 is a great example. In the non-heat-treated state (6061-TO), it is quite bendable. But it is so soft, if you try to machine it, it will gum up the gullets of your saw and clog the flutes of your drill bits and end mills. It’s like trying to drill taffy. But when heat-treated to T4 or higher (such as 6061-T6 or 6061-T651…T651 being T6 temper plus stress-relived), it responds fine to any machining operation.

Machinability Comparison.

Machinability refers to the ease of drilling, milling, sawing and tapping.

The temper/heat-treat designations range from -O to -T10. The dash T numbers (-T) denote the specific process used to treat the material. For example T1 is “naturally aged,” and T5 is “artificially aged.” T6 is “solution heat treated and artificially aged.” 6061-T6 is heated to the critical temperature, then quenched. Unlike steel, which is hard and brittle after quenching, aluminum is soft. To increase the strength and hardness to the T6 spec, the material is then baked at a low temperature (around 350F) for several hours and then allowed to gradually cool. This is the “artificial aging” process. If you skipped the baking step, the material would, over time, age to T4 on its own. There’s a lot more to explain, and even if I had every page of the magazine, it would not be enough! There are plenty of online resources if you are interested. Just Google “heat treating aluminum,” and you’ll be entertained for hours.

So, when you see an ad that says “made of aluminum” without telling you the specific alloy and heat-treat or temper, it’s a bit like answering the question, “What are you eating?” with “Food.”

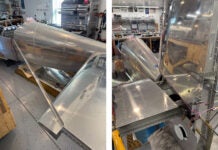

Most metal suppliers have an abundance of rems of different shapes and sizes. Like many dealers, Schorr Metals in Placentia, California, color-codes their stock to help identify the material at a glance.

If you’re working on a project from a well-documented set of plans, or a kit that requires some fabrication of parts from aluminum, the instructions should call out the material specification in detail. The exception might be a part that is not structurally critical. For example, if the plans say: “1 x 1 x 1/8 angle aluminum,” you could source that size angle at a hardware store or home center. What you will likely get is 6063-T5 “architectural grade” aluminum. Compared to 6061-T6, it’s close to same strength and could be a reasonable option. But if the plans specifically call for 2024-T3, there is no option. 2024-T3 is more than three times as strong as 6063-T5 and almost twice as strong as 6061-T6.

So why would anyone use 6061-T6 if 2024-T3 is so much stronger? Cost is one factor. 2024-T3 is twice the price of 6061-T6. Weldability is another. Welding 2024 is generally not recommended. Also, for parts exposed to the elements, 6061 has better corrosion resistance than 2024. These factors and others are considered by engineers when they specify what goes where in your airplane. Engineers will often use 6061 over 2024 and get the same strength by making the part thicker or by gusseting. That’s why it’s important to pay attention. If the plans call for 6061 and you use 2024, it could result in the part being too strong and overstressing an adjoining component. When in doubt, stick to the instructions.

That brings us to buying aluminum stock for shop projects and parts. For non-airplane project material, you might browse local metal suppliers for good deals on surplus (tubing, rectangle bars, plate, or solid rounds, etc.). These are often remnant cutoffs (marked “rems”) that are tossed in a discount bin. Most aluminum is marked by the manufacturer. Anything that is unmarked should be considered “mystery” material. 6061-T6 will be the most common and lowest-price material. A selection of solid round bars one foot long (more or less) from -inch diameter to 1 inches, in -inch increments, would be a good starting inventory for turning stock. Some random angle, hex, rectangle, and plate material are always useful for making do-dads like fixture plates or miscellaneous work-holds.

Your first choice for flying-project material should be an aircraft supply house such as Aircraft Spruce or Wicks Aircraft and Motorsports. In addition to offering the commonly specified grades and shapes, they carry certified material. That is, they get the manufacturer’s test certification that proves the material is what they say it is. Normally you would never need a copy of these “certs,” but you can request a copy with your order. They will charge a fee, but you will get the certification that came with the batch of the material you receive. Both Wicks and Spruce understand that homebuilders aren’t buying for mass production, so they have a “per-foot” price structure. They also offer bargain bags of random sizes and shapes. This is an inexpensive way to practice welding, drilling, riveting, etc., on certified material.

Many aluminum parts can be utilized raw and unfinished. Untreated aluminum that is exposed to the elements, such as a polished fuselage or wings, panels, etc., should be kept clean, waxed, and inspected regularly. The need for corrosion-proofing depends on the alloy and the application. If the part is to be painted, it usually needs to be treated with an Alodine coating or processed with a chromic acid or sulfuric anodize treatment. Pure aluminum and some alloys resist corrosion due to naturally occurring aluminum oxide forming on the surface. In order for paint to adhere, Alodine treatments and the anodize process chemically etch the aluminum oxide away and replace it with a film (Alodine) or surface treatment (anodize) that is compliant to paint.

Aircraft Spruce has a nice overview on their web site that provides additional details about aluminum alloys, heat treating designations, and cross references to pre-WW-II era nomenclature.

The body is made from aluminum, not the frame. Please correct this.

I really enjoyed this informative article Bob. As someone new to all this, it really is a find introduction to metals.

ever would have thought that a part could be TOO strong for certain applications and situations.

Very eye-opening!